Wetlands, Farmers, Just Ducky

Veronica Nigh

Former AFBF Economist

Between the 2018 Farm Bill, USDA’s interim final rule for “Highly Erodible Land and Wetland Conservation” programs and the Environmental Protection Agency’s revised Clean Water Rule we’ve been talking a lot about wetlands. So, what do we really know about wetlands in the U.S.? Are there more or less of them? Are private property owners or state or federal governments making investments to ensure wetlands are preserved? If efforts are underway, are they working or not? To the Prairie Pothole Region, an important stop in the migratory duck flyway, we go for answers!

According to Ducks Unlimited, each spring millions of ducks and geese pass through the PPR, which lies within Iowa, Minnesota, North Dakota, South Dakota and Montana. The PPR, with its wetlands and grasslands, provides important breeding habitat for the 10 most common species of ducks: mallards, gadwalls, American wigeons, green-winged teal, blue-winged teal, northern shovelers, northern pintails, redheads, canvasbacks and scaups. Nest success and hen mortality during breeding are the most important factors related to change in mid-continent duck populations.

Given the importance of the PPR to our feathered friends, it is no wonder that wetland inventories are so closely watched. Data from USDA and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service reveals that farmers, who are often also sportsmen, have taken habitat preservation seriously and the results are something to quack about.

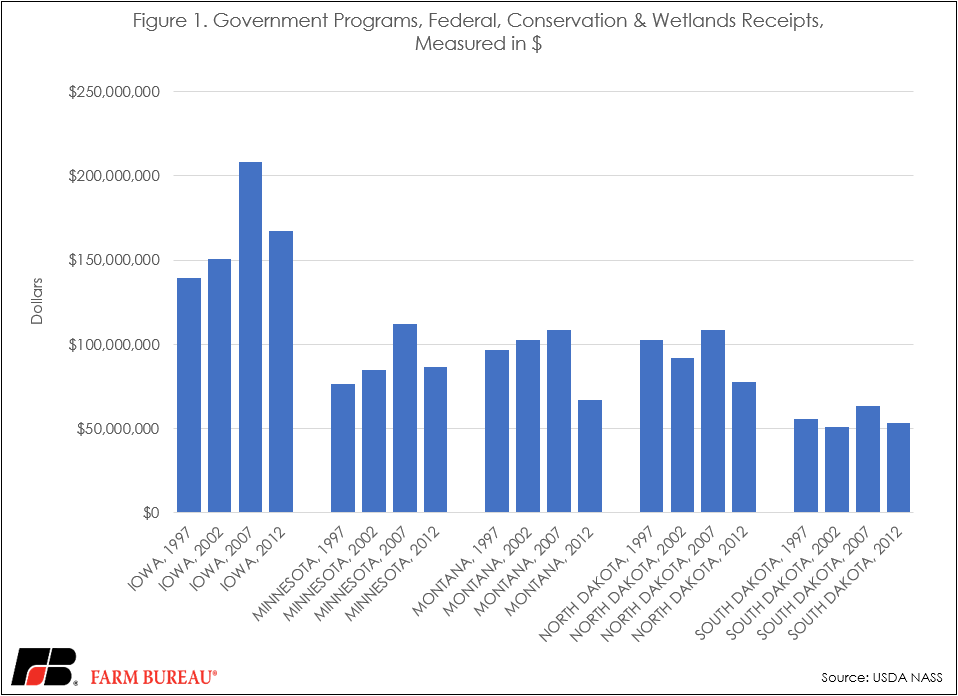

Within the PPR, farmers have heavily participated in federal conservation and wetlands government programs. In fact, between 1997-2012 more than $2 billion was spent on these programs in the PPR alone.

The largest federal program in which farmers have participated is the Conservation Reserve Program. CRP is the largest federally administered private-land retirement program, with annual outlays approaching $2 billion per fiscal year. Over the last 15 years, the number of CRP acres enrolled in wetland and buffer practices has more than doubled, from 2.5 million acres to nearly 5.3 million acres, despite an overall decline in CRP acres. In 2018, 23 percent of all CRP acres were enrolled in these practices, up from 7 percent in 2004. That means that today, nearly one in four acres enrolled in CRP has wetland and buffer practices on the landscape. The 2018 Farm Bill will expand CRP acreage to 27 million acres by 2023, up from the current 24 million acres. If the trend of installing wetland and buffer practices on CRP lands continues, an increase in wetland acres is likely.

In addition to CRP, landowners have also utilized the Wetlands Reserve Program, which is a voluntary program that offers financial support to landowners for wetlands restoration and protection projects. Across the U.S., over the last decade, nearly $3 billion has been invested over 2.6 million acres in this program alone. Of those totals, over 300,000 acres and nearly $0.5 billion in funding has been directed to the PPR.

Meanwhile, although the mix of crops planted in the PPR may have changed over the years, the total number of acres planted to cropland has remained virtually the same. This means that in spite of high commodity prices a few years ago, farmers did not plow under their prairies or drain their wetlands en masse. Instead, they remained committed to maintaining conservation efforts, alongside their farming and ranching operations.

In addition to farmers and ranchers, the Fish and Wildlife Service is also doing its part to ensure that wetlands are prevalent. In the last 15 years, acreage under FWS control has increased by nearly 1.3 million acres in the PPR, an increase of 26 percent. This has brought total FWS acreage in the region to 6.2 million acres. Nationally, FWS controls more than 855 million acres across the U.S. and its territories.

So, how have our feathered friends fared? According to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s Waterfowl Population Statistics, 2018, efforts to preserve wetlands seem to be working. The report estimates the number of ponds available to nesting ducks within the northcentral U.S. (Because nesting ducks are territorial, the number of ponds, not just the overall acreage of ponds is important.) Figure 3 reveals the number of ponds, which are highly dependent on rainfall, has averaged higher over the years since the 1996 farm bill was passed. This larger number of May ponds should mean a larger duck population. And indeed, according to the same FWS report, in the traditional PPR survey area, the total duck population estimate in 2018 was 41.2 million birds. This estimate is 17 percent higher than the long-term average (1955–2017). Figure 4 tracks the population of the top 10 duck species in the PPR since 1955.

Trending Topics

VIEW ALL