Using Geographical Indications as Barriers to Competition in Dairy

TOPICS

TradeWilliam Loux

Global Trade Analyst

photo credit: Alabama Farmers Federation, Used with Permission

William Loux

Global Trade Analyst

With the U.S. Trade Representative preparing to publish the Special 301 Report on intellectual property issues, the European Union’s continued utilization of geographical indications, or GIs, as barriers to competition returned to the forefront of policymakers’ minds. Under EU policy, GIs moved beyond protecting a product specific to a region or city, like Idaho potatoes or Parma ham, into products that have a long history of production in many different regions and countries. In doing so, the EU seeks to keep competitor-produced cheese out of markets by claiming sole ownership of common cheese names, like feta or parmesan. This forces non-European suppliers to change their products’ names to more descriptive, but unfamiliar terms, like “crumbled sheep cheese” or “hard grated cheese.” This strategy is not limited to the EU’s internal market; Restrictions on common food names are becoming a fixture in EU-negotiated free trade agreements, like the EU-Canada Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement and the EU-Japan Economic Partnership Agreement.

New Study Details Consequences of EU GIs

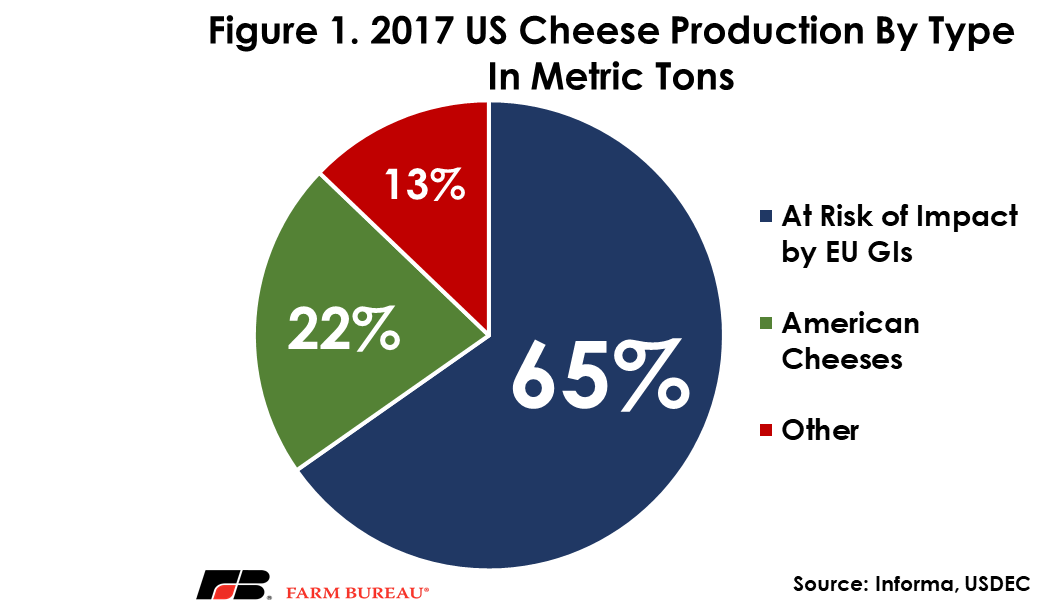

A newly published study by Informa Agribusiness, prepared on behalf of the U.S. Dairy Export Council, quantifies the potential damage to U.S. dairy farmers and the broader industry if the EU’s system of geographical indications applied globally. Based on other instances of GI implementation within the European Union and trade agreements that included GIs, the study found that consumers would face higher prices for the same cheese imported from abroad, and U.S.-produced cheese would suffer from having to rebrand.

According to the Informa study, U.S. consumption of domestically produced cheese would immediately fall by 306 million pounds, to 814 million pounds, depending on how much more consumers are willing to pay for recognizable cheese names. This decline in consumption is magnified if other popular cheeses, like mozzarella and provolone – cheeses for which European producers previously wanted protection but are not currently considered GIs – are included. Indeed, lost consumption would extend beyond the U.S. to our largest export markets, with over $300 million of U.S. sales lost over 10 years in Mexico and South Korea alone.

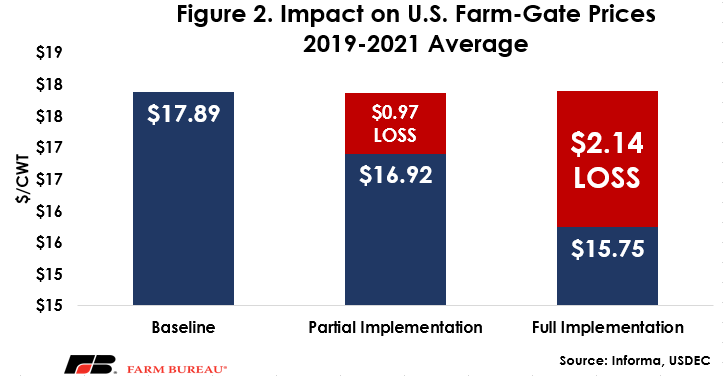

Harm to U.S. Farmers

The reduced consumption would then translate to lost revenue across the dairy industry, directly impacting farmers’ milk checks. The study estimates that dairy farmers would see their average milk price fall by 97 cents per hundredweight, to $2.14 per hundredweight, pushing many farmers out of business. This combined drop in prices alongside reduced production from diminished profitability could push total farm gate revenue losses over $20 billion in just the first three years after implementing GI restrictions.

Summary

Fundamentally, introduction of European GIs would lead to higher prices for consumers, reduced consumption for U.S. cheeses, and lower prices for farmers. Thankfully, for the time being, this remains a hypothetical. Consumers can still purchase feta, asiago, gouda and parmesan made by American cheesemakers. But, as made clear in Informa’s analysis, defending the continued use of common food names is essential for dairy farmers, processors and consumers.

Trending Topics

VIEW ALL