USDA Finalizes Hemp Rule

TOPICS

USDAMichael Nepveux

Economist

photo credit: AFBF Photo, Philip Gerlach

Michael Nepveux

Economist

On Jan. 19 USDA’s Agricultural Marketing Service published the final version of the rule clarifying regulations for the production of hemp in the United States. The 2018 farm bill legalized the production of hemp as an agricultural commodity and removed it from the list of controlled substances. In October 2019, USDA released the text of its interim final rule for regulations, establishing a domestic hemp production program. Since this was an interim final rule, it went into effect immediately upon being published in the Federal Register. Many agricultural organizations, including the American Farm Bureau Federation, submitted comments on the interim final rule by the January 2020 deadline. In its final rule, USDA incorporated some of the suggestions that came in through the various comment periods and applied some of the lessons learned over the previous few years of growing hemp. Several of these changes will ease the regulatory burden on hemp farmers as they become effective on March 22. However, while USDA has issued this final rule, the Biden administration is in the process of identifying recent rules for additional review.

Hemp in the U.S.

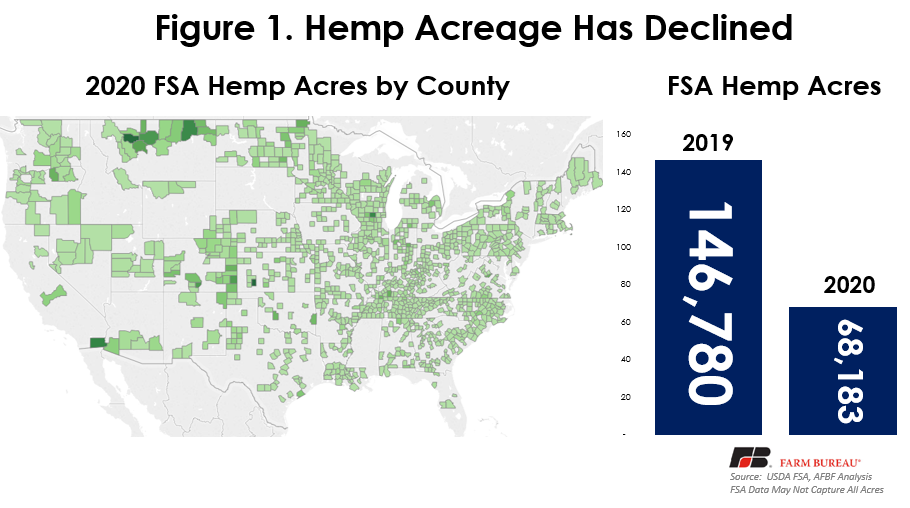

With the removal of hemp from the list of controlled substances, interest in the crop exploded across the country. As states legalized hemp production within their borders, farmers rushed to grow this promising new crop. However, from 2019 to 2020 acres planted to hemp declined dramatically, according to USDA’s Farm Service Agency, with the top three states – Montana, Colorado and Kentucky – accounting for 78% of the decline. Area planted in those states dropped by over 61,000 acres, which is nearly as many acres as the 68,000 acres planted across the entire country in 2020.

The acreage decline may be partly due to waning interest from producers and cratering prices for the crop, but there have also been many producers who grew the crop with no market to sell it into, among other frustrations. However, another issue that may be driving much of the drop in acreage is potential underreporting by producers. Previously, particularly for 2019, planted acreage reporting for hemp was still largely on a voluntary basis. Now hemp producers are required to report their acreage to FSA, making it all the more concerning there still appears to be a lack of reporting. Due to these factors, it is challenging to distinguish if the driving force behind the decline in reported acres is largely because of an actual decline due to deteriorating market conditions, or if hemp growers are underreporting.

Changes in the Final Rule

The ambiguity in the farm bill concerning testing procedures and other aspects of the law generated were many questions about the production of this crop. In attempting to clarify the regulations in the interim final rule, USDA addressed some of the challenges, but inadvertently created additional concerns. This final rule includes several critical changes that were requested by many in the industry, including Farm Bureau.

Sampling

As there was little uniformity across states in how the crop would be tested, stakeholders were hoping the IFR would provide some clarity on the testing process; some states would test just the top 8 inches of a plant, while others would test 6 inches, and there was little consistency in how to build up a statistically significant sample of a farmer’s crop. This new final rule allows states and tribes to adopt a performance-based approach to sampling in their plans. AMS feels that sampling requirements should allow states and Indian tribes more flexibility in the management of their hemp regulatory programs. However, the alternative method must have the potential to ensure, at a confidence level of 95%, that the plant will not test above the acceptable hemp THC level. The plan must be submitted to USDA for approval. It may take into consideration state seed certification programs, history of producer compliance and other factors determined by the state or tribe. For producers licensed under the USDA plan (as opposed to a state plan submitted to USDA), new modified sampling requirements are laid out in this rule. The sample must be taken approximately 5 to 8 inches from the “main stem” (including the leaves and flowers), “terminal bud” (at the end of a stem) or “central cola” (cut stem that could develop into a bud) of the flowering top of the plant. This new sampling requirement may result in more stem and leaf material being included in the sample, which could help to reduce the number of crops that test “hot.”

The rule also modified the sampling timeline. Originally, the IFR gave a 15-day window to collect samples before harvest. However, there was much confusion surrounding this. For example, if a sample is pulled 15 days before anticipated harvest, would harvest be allowed if there is a backlog at the testing laboratory and the results are not back in time? The THC concentration typically increases as the plants mature, so a crop could potentially rise above the threshold if the testing process isn’t completed early enough in those 15 days. Additionally, does the 15-day window mark the beginning of harvest or the end of harvest? Some fields may take multiple days to harvest and could conceivably be started before but finished after the 15-day window closes. AMS ultimately agreed with the arguments presented in many of the public comments that this 15-day window would impose significant challenges. As a result, AMS expanded this collection window to 30 days, which will ease the burden that hemp growers faced from the shorter window.

Testing

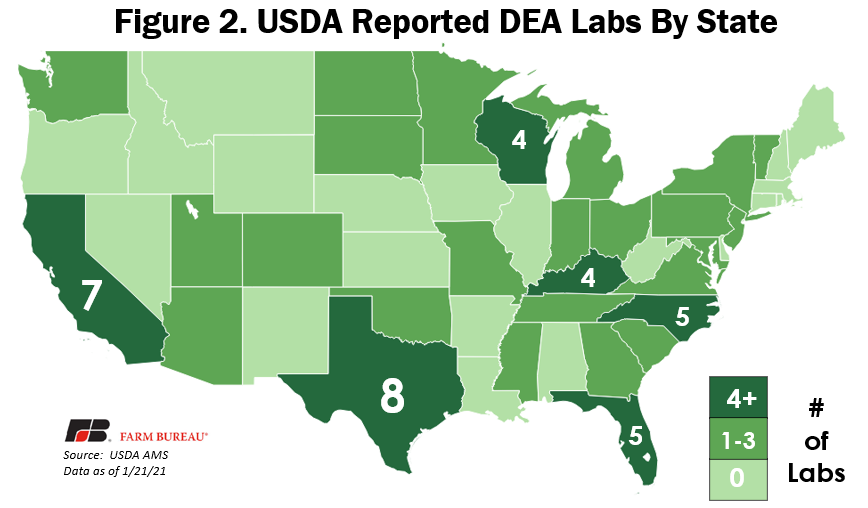

The original rule required that testing be completed by an approved Drug Enforcement Administration-registered laboratory using reliable methodology for testing the THC level. On Jan. 30, 2020, USDA reported only 44 approved laboratories in 22 different states. Having such a small number of laboratories approved to test samples from the (at the time) hundreds of thousands of acres in the U.S. was sure to result in backlogs and delayed testing times. When combined with the 15-day harvest window, some farmers were concerned about their ability to harvest their crop within the window. On Feb. 27, 2020, USDA announced the delay of enforcement of the requirement for laboratories to be registered by the DEA and the requirement that producers use a DEA-registered reverse distributor or law enforcement to dispose of non-compliant plants under certain circumstances until Oct. 31, 2021, or the final rule is published, whichever comes first.

At the time of publishing the new final rule, the testing bottleneck had not improved much. Figure 2 shows which states have a registered DEA-approved laboratory available for testing and listed on the AMS website. As of Jan. 21, 2021, there were only 70 approved laboratories in 28 different states. While this certainly marks an improvement over this time last year, it still presents a major bottleneck. AMS recognized this bottleneck and extended the delay of requiring DEA-approved laboratories through Dec. 31, 2022.

Negligence

Producers must dispose of plants that exceed the acceptable hemp THC level. However, if the plant tests at or below the negligent threshold stated in the rule, the producer will not have committed a negligent violation. The final rule raises the negligence threshold from .5% to 1% and limits the maximum number of negligent violations that a producer can receive in a growing season (calendar year) to one. This means that if hemp tests above 0.3% but below 1%, it will not be considered a negligent violation (but will still need to be destroyed). If a producer tests above the 1% level, the producer will receive a notice of violation from USDA, as well as a corrective action plan that the producer would be required to follow by a certain date and report back to USDA. Because the number of violations that a producer can receive are limited to once per year, this means that if multiple lots or fields test above that level, they will not receive multiple violations. If a producer receives more than three negligent violations in five years, they will be ineligible to participate in the program for a five-year period.

Disposal

Previously, the IFR had strict requirements for disposal or remediation of hot crops. It required the DEA or another entity authorized to handle marijuana under the Controlled Substances Act to dictate the process for disposal. This was likely to create unnecessary and costly burdens on both the farmers and the states and tribes managing their hemp programs. AMS listened to many of the comments submitted by stakeholders and gave producers additional options beyond total destruction. The guidelines for these methods are provided in a guidance document separate from the final rule (located here). The new methods for disposal include plowing the crop under, mulching or composting, disking, mowing or chopping down, burning and burying at a depth of at least 12 inches. Many of these methods are more economical and preferred by producers over the stricter requirements laid out in the IFR.

Summary

The 2018 farm bill legalized the production of hemp as an agricultural commodity and removed it from the list of controlled substances. In October 2019, USDA released its IFR for establishing a domestic hemp production program. This week, USDA published its final hemp program rule, which is slated to go into effect on March 22. The rule includes a number of improvements ranging from a longer window of time between crop testing and harvesting, to a better sampling method and a higher threshold for negligent violations.

Trending Topics

VIEW ALL