The Squeal is Real - U.S. Pork Exports to China Plummet

TOPICS

Trade

photo credit: Alabama Farmers Federation, Used with Permission

Veronica Nigh

Former AFBF Economist

In a typical year, the majority of U.S. pork exports to China occur within the first seven months, with peak exports occurring in April through June. But as everyone is aware, 2018 has been anything but typical on the trade front. On April 2, U.S. pork, fruits, nuts, wine and ginseng found themselves on the receiving end of China’s irritation about recently imposed U.S. steel and aluminum tariffs. The irritation came in the form of an additional 25 percent tariff on U.S. pork and an additional 10 percent tariff on the rest of the targeted agricultural products. While there have been ad hoc reports of declining sales and suspiciously thorough port inspections for the non-pork products on the list, complete data has been hard to come by. But for U.S. pork, the significant impact these tariffs are having on U.S. export volumes is more apparent because of mandatory export reporting. The data is clear – U.S. pork exporters are squealing, but with dismay, not delight.

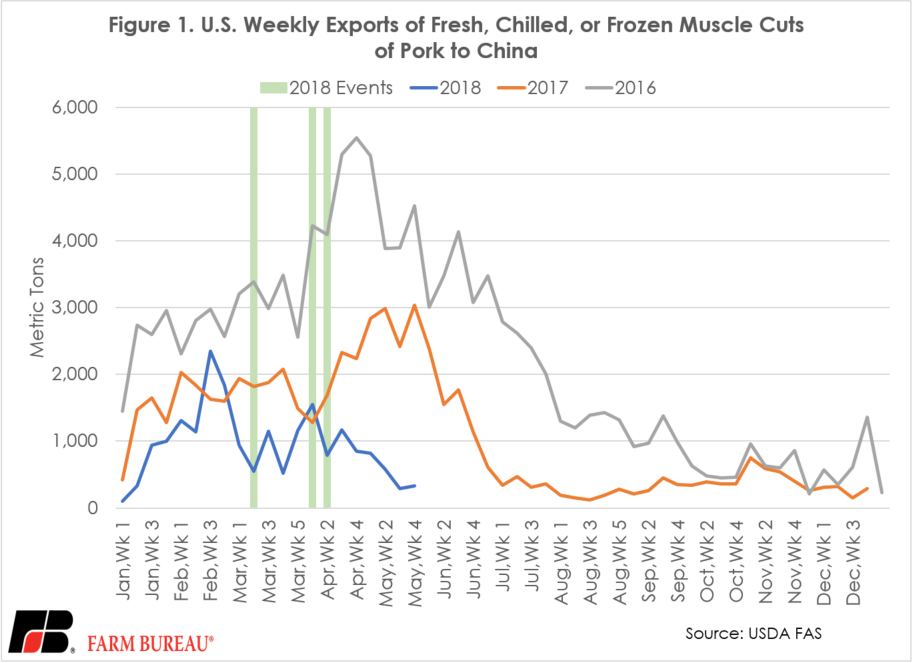

Very quickly, a reminder of a few relevant dates: March 1, U.S. tariffs on steel and aluminum imports were announced; March 23, the new tariffs went into effect; April 2, China countered with tariffs aimed at more than 120 U.S. products. These events, unfortunately all too common as of late, are designated by green bars in Figure 1.

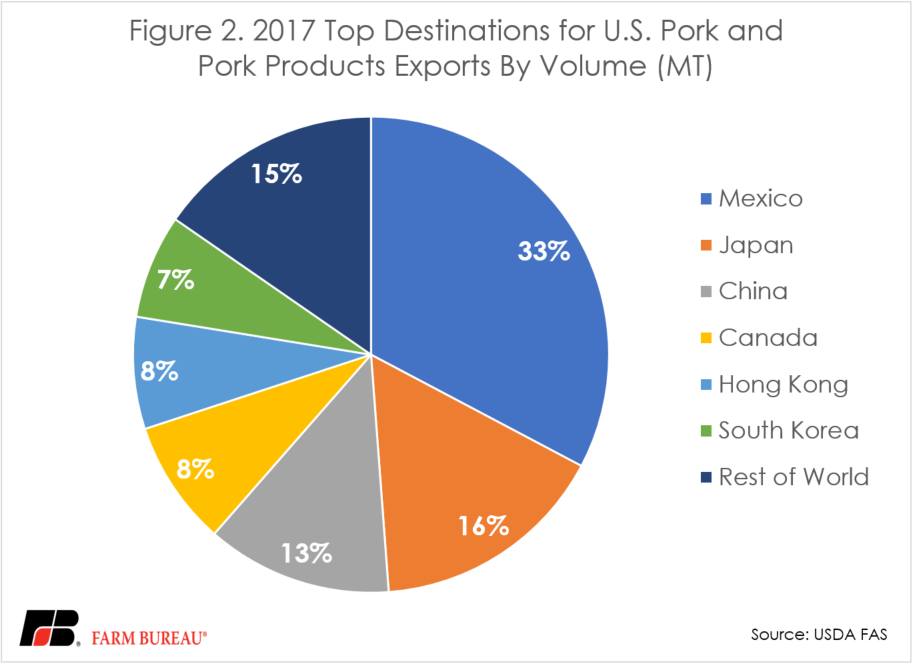

In Figure 1 we note that the volume of U.S exports of pork to China has varied considerably over the last three years. In 2016, the 362,000-plus metric tons of U.S. pork and pork products exported to China set new records. The next year, pork exports were down nearly 15 percent, yet China solidly remained the third-largest market for U.S. pork, as it has been since 2011. In 2017, China represented 13 percent of U.S. pork exports, as depicted in Figure 2.

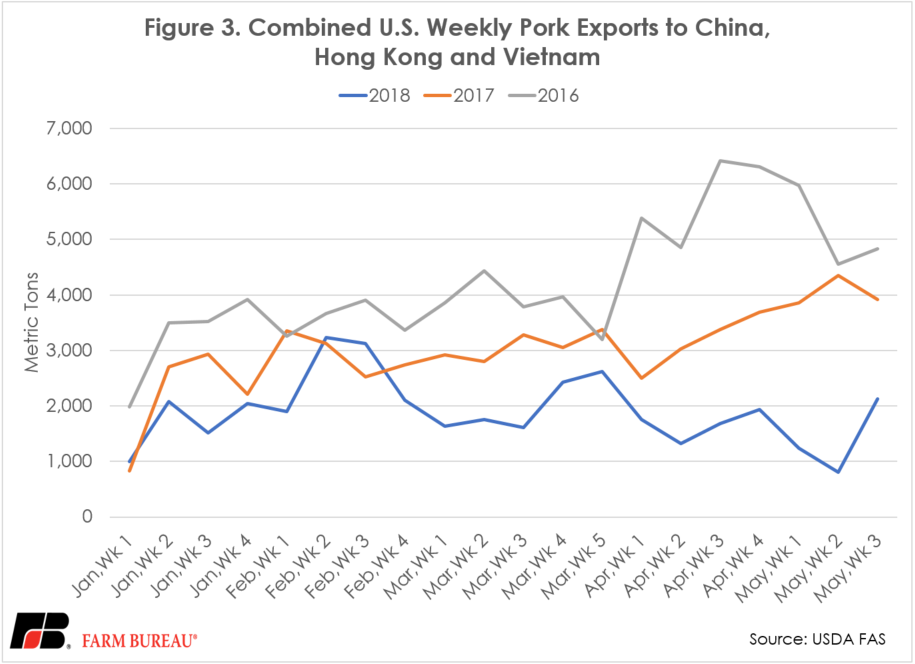

For those who follow trade with China, the next question that comes to mind is “what is happening in Hong Kong and Vietnam?” When actions that impact trade between the U.S. and China, Hong Kong or Vietnam occur, we often observe an increase in trade between the U.S. and one or both of the other two markets. In fact, because of the gray market that exists between China, Hong Kong and Vietnam, these three markets are often referred to as a single market. In 2017, nearly half a million pounds of U.S. pork and pork products, or 1 of every 5 pounds of exported U.S. pork was destined for China, Hong Kong and Vietnam. However, as shown in Figure 3, 2018 combined weekly exports of U.S. pork to these three markets do not suggest any sizable diversion is occurring, at least not yet. So far, the additional 25 percent tariff China has applied to U.S. pork seems to be having the intended effect - a reduction in U.S. pork exports to China.

Trending Topics

VIEW ALL