The EU-Japan EPA, What Does it Mean for U.S. Agriculture?

Veronica Nigh

Former AFBF Economist

A Short Econ Lesson

For the purpose of growing the economy and increasing consumption, economists tend to favor trade agreements in the following order: multi-lateral, regional, bilateral. Why? In a multi-lateral agreement (think the World Trade Organization or WTO negotiations from years back) tariffs on goods are lowered from all countries, causing consumer prices to fall and allowing a consumer to buy more product with the same income level. In essence, your consumer dollar stretches further. In a regional agreement (think the Trans-Pacific Partnership or TPP negotiated under the previous administration and abandoned by the current) tend to encompass more countries, so in ways they are similar to a multi-lateral, but because the member countries are not in the same kind of global deal, they may not make as many reforms as they would have in a global setting. In a bilateral agreement, (think the recent agreement between the EU and Japan) the price of goods sourced from the other country party to the agreement falls, but goods from other sources stay the same. Again, think the price of EU cheese going into Japan is going to fall, but that from the U.S. will remain the same. Rather than expanding consumers’ purchasing power, a bilateral agreement tends to lead consumers to substitute products, buying products from the FTA partner country, rather than products from non-FTA countries still facing the higher tariff. Bilateral trade agreements tend to shift market share, but don’t create as much new trade. Regional trade agreements lie somewhere in between because they tend to encompass more countries than bilateral agreements, but not as many as multilateral agreements.

EU-Japan Economic Partnership Agreement

Understanding the hierarchy of trade agreements is key to understanding why the EU-Japan FTA, announced this week, is such a threat to U.S. agricultural exports to Japan. Japan has long been a key market for our industry, consistently ranking as the fourth largest market for U.S. agricultural products. In 2016, the U.S. sent $11 billion worth of U.S. agricultural products to Japan, more than 8 percent of our total exports. We have achieved this export success on the back of high-quality products, strong trade servicing, and consistent marketing.

Despite this success, the U.S. could do better. Japan continues to maintain high tariffs on agricultural goods, especially when compared to other developed economies. Reductions in these tariffs will certainly mean greater sales for the country able to reach and ratify a trade agreement. This is why American Farm Bureau Federation and the vast majority of the U.S. agricultural community celebrated the signing of the TPP on February 4, 2016, and mourned the U.S. withdrawal on January 23, 2017.

The EU recognized the U.S. withdrawal from TPP as an opportunity. While negotiations between the EU and Japan began on March 25, 2013, the negotiations went into hyper-drive once the U.S. withdrew from TPP. The laser focus produced an announcement on July 5 that an agreement had been reached. The EU agricultural community is bullish. In fact, EU Commissioner for Trade Cecilia Malmström stated "We hope that we could triple our agriculture exports. EU exports to Japan overall could, according to our calculations, be boosted by one-third." The EU exported more than $6.5 billion in agricultural goods to Japan in 2016, which is also the EU’s fourth largest market.

The agreement still has a number of details to be hammered out and in any case, is not expected to be implemented until early 2019.

So what does it mean for U.S. agriculture? Unfortunately, it likely means that we will lose market share in an important market – that’s what tends to happen when you’re outside looking in on a bilateral FTA.

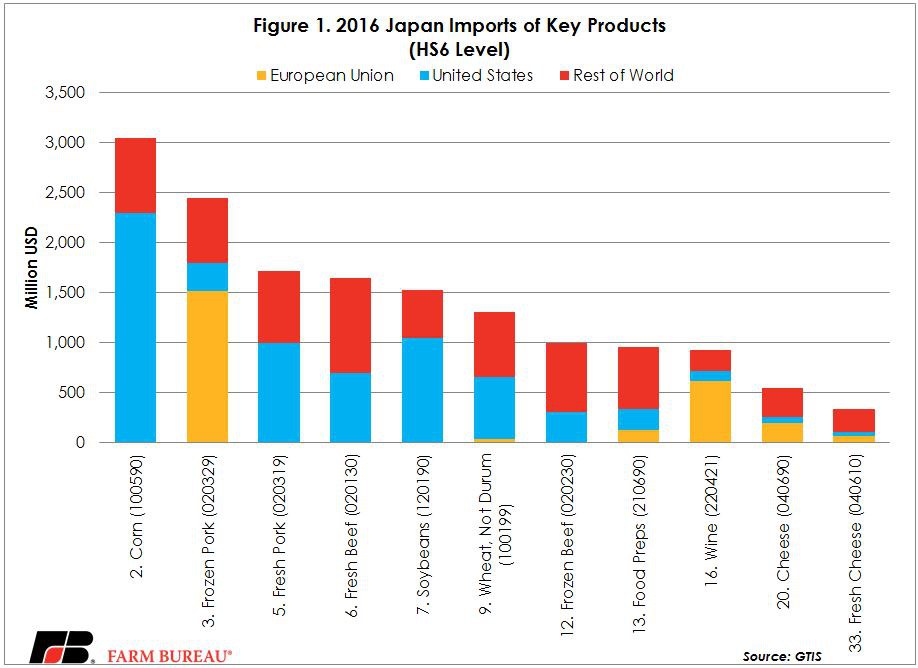

The U.S. competes head to head with the EU in a wide variety of products. Figure 1 gives a graphical representation of some of Japan’s top imported products and how we compare to the EU. U.S. exports of some products, like corn and soybeans, probably won’t experience a significant impact. These are not products the EU specializes in, can’t grow enough of, or simply are so far out of price competition with the U.S. that strong competition isn’t likely. For other products, like pork, beef, processed foods, wine, and cheese, however, this agreement could lead to significant erosion of U.S. market share. The EU already has a strong presence in the Japanese market that a significant tariff advantage will only improve. The adoption of European-style rules on non-tariff issues such as geographic indicators, technical barriers to trade, sanitary and phytosanitary measures will also challenge U.S. competitiveness.

Upon review of the initial results of the EU-Japan FTA, it appears the EU got a deal very similar to what the U.S. would have gotten under TPP. But don’t take our word for it. The details of the TPP are still available here. An early draft of the EU-Japan FTA results is available here. Time stands still for no man, nor does trade wait for U.S. agriculture.

Trending Topics

VIEW ALL