Tariff Threats Roil Crop Markets

TOPICS

Trade

photo credit: Arkansas Farm Bureau, used with permission.

John Newton, Ph.D.

Former AFBF Economist

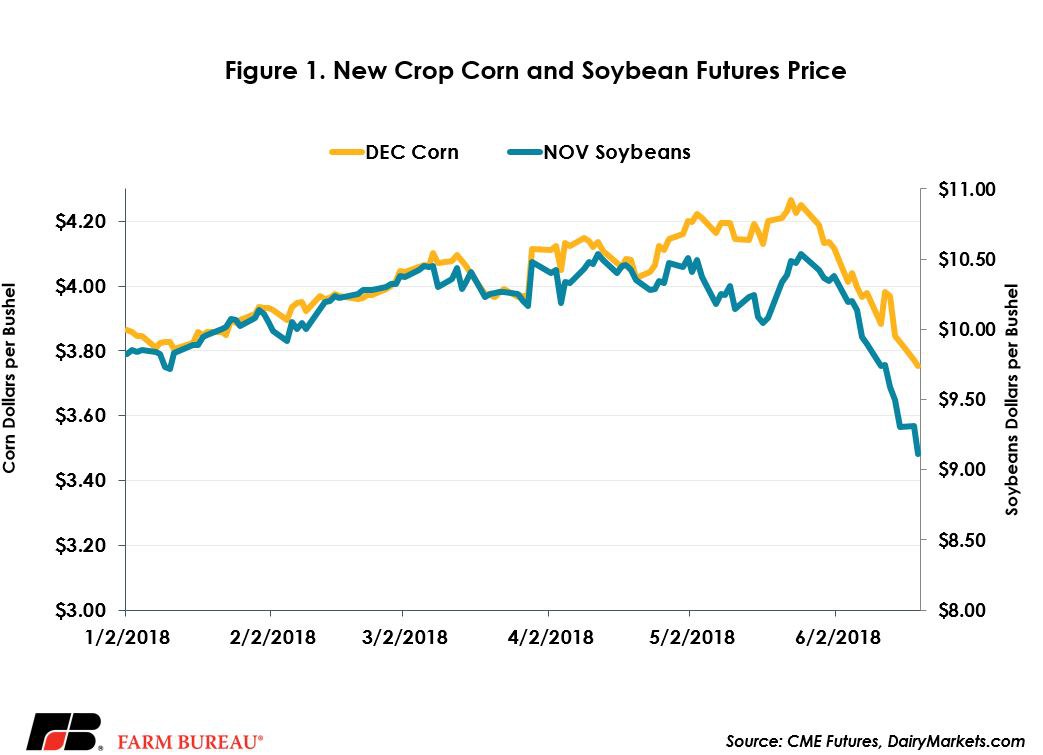

Following a late-May price rally that coincided with a “cease fire” in the tit-for-tat trade tensions between the U.S. and China and a commitment by China to “ramp up” purchases of U.S. agricultural commodities, many commodity futures contracts traded at or near contract highs in 2018. For example, new-crop corn reached a high of $4.265 per bushel on May 23 and new-crop soybeans reached a high of $10.535 per bushel two days later. Largely due to poorer than anticipated cotton crop conditions, i.e. only 42 percent of the crop in good-to-excellent condition as of June 10, new-crop cotton futures reached a high of 95.2 cents per pound on June 11.

By mid-June, shortly after Commerce Secretary Ross returned from China, the trade tensions had not only resumed, but they intensified. On June 15, the U.S. announced a 25 percent tariff on $50 billion worth of Chinese products and China responded quickly by releasing version 2 of the 301-probe list capturing 90 percent of U.S. agricultural exports to China (The Never-ending Retaliatory Tariff Exchange, China Edition). When, three days later, on June 18, the U.S. announced plans to identify $200 billion in Chinese goods to target for tariffs, commodity prices plummeted.

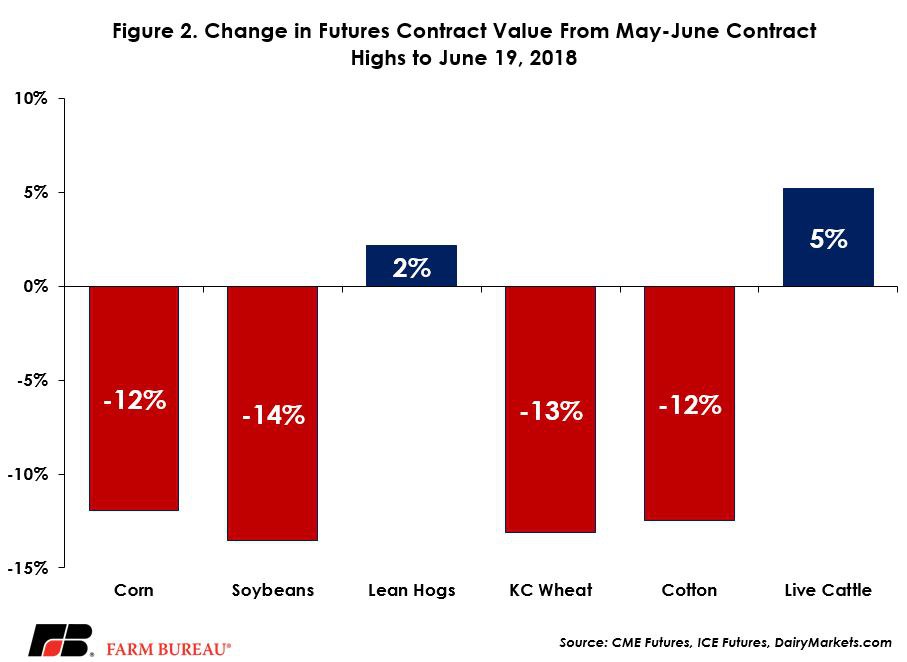

At closing on June 19, many futures contracts traded to contract or multi-year lows, in large part due to the combination of favorable growing conditions and mounting trade tensions. New-crop corn and soybean futures fell to their lowest levels of the year at $3.755 and $9.11 per bushel, down 51 cents and $1.42 per bushel, respectively. Kansas City wheat futures fell to $4.83 per bushel, down from $5.56 in mid-May, a loss of 73 cents per bushel. Cotton fell to 83.3 cents per pound – but likely is finding support due to poor crop conditions and the potential impact on the crop size. Finally, pork and cattle also fell slightly on news of escalating trade tensions, but remain above their mid-May futures contract values.

The escalating trade tensions have had an impact on the futures contract and cash values for a variety of crops. For farmers marketing old-crop corn, soybeans, cotton or wheat, the declining futures and cash market values could reduce farm profitability. For farmers actively attempting to market their new-crop corn, soybeans, wheat or cotton, the increased price volatility impacts their ability to manage price and revenue risk. For example, the $1.42 per bushel decline in new-crop soybean futures is equivalent to $5.9 billion on the 4.3-billion-bushel soybean crop. Similarly, the decline in new-crop corn prices is equivalent to $7.2 billion based on the projected size of the crop.

A Timely Resolution is Encouraged

Historically, farmers and ranchers have had to deal with a variety of uncertainties. These uncertainties include but are not limited to risks from weather, pests or disease that could result in crop or livestock losses; shifts in global supply and demand and the impact on market prices; increased uncertainty associated with regulatory compliance; and the ability to find and hire the labor needed to harvest a crop or care for animals.

Now, farmers and ranchers are facing market uncertainty in a tit-for-tat trade dispute. Will farmers and ranchers face tariffs of 25 percent or more by the time combines begin to roll across the Corn and Cotton belts? Or will China and other partners reduce the barriers to trade and ramp up purchases of U.S. agricultural products such as beef, pork, corn, cotton and soybeans?

While other sectors of the U.S. economy are surging, the farm economy is facing adversity from many angles such as low commodity prices and income, rising interest rates, record debt and poorer loan performance. One factor that will certainly help to improve the farm economy, and is in the best interest of U.S. agriculture, is a timely and successful resolution of these trade disagreements.

Trending Topics

VIEW ALL