Tariff Motivation 101, Reviewing the U.S. Trade Deficit

TOPICS

TradeJay Rempe

Senior Economist

photo credit: AFBF Photo, Mike Tomko

Jay Rempe

Senior Economist

As a presidential candidate and throughout his 18-plus months in office, President Trump has committed his administration to reducing the U.S. trade deficit in goods and services. According to the administration, the trade deficit is evidence that the U.S. is “losing” in international trade and could hinder growth in U.S. gross domestic product. By reducing the trade deficit, the administration seeks to accelerate economic growth and job creation in the U.S.

A trade deficit or surplus is a financial accounting of the flow of goods and services between one country and the world. A trade deficit occurs when a country imports more than it exports. Importantly, trade deficits and surpluses are influenced by a variety of factors including currency values, consumption, savings and investment rates.

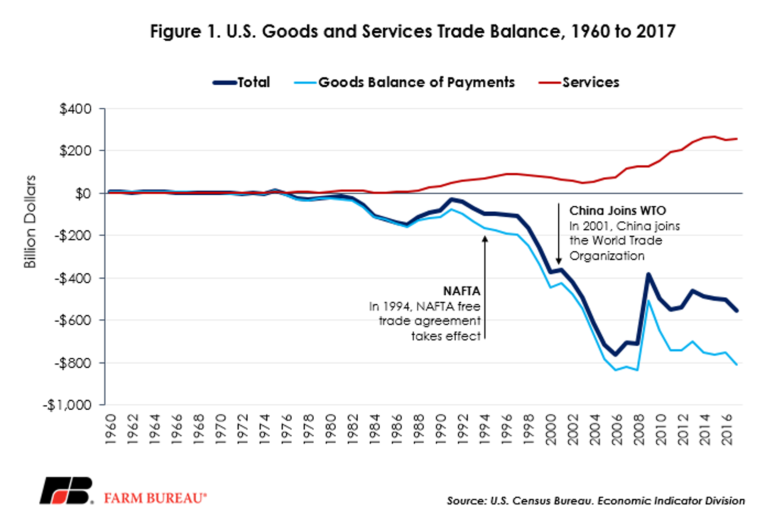

The U.S. has run a negative trade balance for nearly 50 years and each year the trade deficit exceeds hundreds of billions of dollars. In 2017, the trade deficit was $552 billion in total and represented an $807 billion trade deficit in goods and a $255 billion surplus in services.

Figure 1 shows not only the annual U.S. trade balance since 1960, but also how various factors can impact trade’s ebbs and flows. For example, following the recession in 2009, U.S. consumption levels fell dramatically, and as a result, imports into the U.S. dropped and the trade deficit declined to the lowest levels since 2001.

While the U.S. has a trade deficit in a number of good and services, U.S. agriculture is one of the few sectors that consistently runs a trade surplus. The agricultural surplus in 2017 was $17.2 billion, and over the last decade U.S. agriculture has contributed over $300 billion in trade surpluses. For 2018, USDA’s May Outlook for U.S. Agricultural Trade projected U.S. exports at $142.5 billion and imports at $120 billion. If realized, this would result in a trade surplus of $21 billion, up 22 percent from 2017 and the highest level since 2014. Figure 2 highlights the trade surplus in agricultural products.

It’s well documented that trade deficit reduction is a driving force behind the administration’s position on international trade. The administration is attempting to address the trade deficit on multiple fronts simultaneously including renegotiating the North American Free Trade Agreement, revising the Korea-U.S. free trade agreement, launching a Section 301 probe against China and imposing section 232 tariffs on imports of steel and aluminum.

For agricultural producers on the front lines of these trade disputes, two big questions emerge: First, are trade deficits inherently bad? And, second, is the U.S. losing to the rest of the world by having such large trade deficits?

Are Trade Deficits Good or Bad?

Economists do not unanimously agree that a reduction in the deficit will lead to economic growth and job creation. Those in favor of trade argue that trade deficits follow gross domestic product, i.e., they are influenced by strong consumption levels and downward pressure on currency values through the lack of savings and investment. Those against trade deficits claim they weaken GDP and can be a threat because the country is buying more than it is selling. This theory, importantly, does not consistently agree with empirical evidence from the U.S. economy and its trade deficit.

The first theory is supported by evidence. U.S. GDP continues to grow year-over-year and the U.S. economy is consumer-driven -- meaning Americans are more prone to spend than save. In this context, imports are an important component of meeting consumer demand. Thus, the trade deficit is largely a reflection of underlying economic conditions and consumer demand. When consumers are spending and the economy is growing, the U.S. trade deficit widens. When consumers cut back on spending and the economy is shrinking, the trade deficit narrows. The U.S. tends to run an ongoing trade deficit because it is the world’s largest, most dynamic economy. A growing trade deficit, if anything, is indicative of the underlying strength of the U.S. economy. This would support the theory that trade deficits are not a bad thing.

When U.S. consumers purchase products from businesses in other countries, they use U.S. dollars. In turn those foreign businesses, more often than not, use those U.S. dollars to purchase U.S. goods, assets, companies or facilities. Dollars generated by imports are also used to finance trade and investment in other countries, which help grow the world’s economy. Thus, the ebb and flow of goods, services and capital throughout the world all have an influence on the U.S. trade deficit.

Is the U.S. Losing?

In response to the second question, the U.S. isn’t inherently a loser or winner because it has a trade deficit. Countries do not trade. People and businesses trade—it is the central Nebraska popcorn producer who sells to a theater chain in Mexico; the Kansas wheat farmer whose wheat is shipped to Japan; the Iowa equipment manufacturer that sells farm equipment in the Middle East; the U.S. crop protection company that buys supplies from a Chinese chemical company; or the Virginia consumer who purchases French wine.

When trade happens, the transaction wouldn’t occur unless both the seller and purchaser are satisfied. And presumably, both parties are made better off by the transaction. The sum of all these transactions equals either a trade surplus or deficit. That’s not to say there aren’t losers from trade. There are—mostly producers who are unable to compete with imported products. A trade deficit, though, isn’t the reason for the losses. Rather, as David Ricardo identified in the early 1800s, it is competitive advantages in the marketplace. So, no, the U.S. is not losing; we are merely competing in markets in which we have a competitive advantage over others.

Summary

While the administration has made reducing the trade deficit a top priority, there is no evidence to suggest it is a drag on the U.S. economy. Moreover, the trade deficit reflects the strong purchasing patterns of U.S. consumers, i.e., spending versus savings, relative to the consumption patterns in other parts of the world. It also reflects the higher per capita income in the U.S. relative to the counties we trade with. For these reasons, it is anticipated that the U.S. would run a trade deficit.

The existence of a trade deficit is not evidence of bad trade agreements, unfair trade practices or a lack of American competitiveness. It is an accounting of the billions of transactions by individuals and businesses across the globe competing to improve their profitability and economic wellbeing. That’s capitalism, and that’s the American way.

What’s not capitalism, and not the American way, however, are unfair trading practices that put U.S. businesses, including farmers and ranchers, at an unfair competitive disadvantage. Such is the case when it comes to biotechnology approval (Biotechnology Roads Left Untraveled) or intellectual property theft. However, for these challenges the World Trade Organization has dispute settlement mechanisms. At a time when farm income is at a 12-year low, and likely to fall even lower due to recent price movements, tariffs that ultimately come full circle and hurt farmers and ranchers should not be the dispute settlement mechanism.

The $12 billion package of agricultural assistance announced yesterday by the administration will provide a welcome measure of temporary relief to farmers and ranchers who are experiencing the financial effects of the trade war. The package should help many farmers and ranchers weather the rough road ahead and assist in their dealings with their financial institutions. However, our long-term emphasis should continue to be on trade and restoring markets.

Trending Topics

VIEW ALL