Sustainability Markets, Part 4: Is Carbon a Commodity?

TOPICS

Sustainability

photo credit: Mark Stebnicki, North Carolina Farm Bureau

Shelby Myers

Economist

AFBF’s Market Intel is publishing a five-part series to highlight the opportunities, challenges, policy levers and overall operation of agricultural ecosystem credit markets.

This Market Intel article discusses how agricultural ecosystem credits could be priced and purchased, particularly if they were priced as a commodity.

A challenge of agricultural ecosystem credit markets is quantifying the generated assets in a streamlined and cost-efficient manner. After that hurdle is overcome, the next question is how are these assets priced?

How much is an asset worth? An agricultural ecosystem credit can be priced in several ways depending on the type of business that is operating the market. Among current private market-operators, payments are coming in the form of a per-acre cash payment or a per-metric-ton payment. Farmers can either be paid for the practice implemented or be paid based on outcomes. Payments range from 30 cents per acre for research to $3 per acre for a specific practice to $10 per acre for general enrollment or $10 per carbon credit to $15 per credit. These are early estimates and many companies have not publicly announced their pricing proposals. A common question is whether a credit, a sequestered unit of carbon in this scenario, is considered a commodity. And if it is, how does that change the outlook of the carbon market?

A commodity is defined as “an economic good: such as a product of agriculture or mining; an article of commerce especially when delivered for shipment; a mass-produced unspecialized product.” If carbon is considered a commodity, it would need to meet the basic qualification that there is little differentiation between carbon sequestered by one farm and carbon sequestered at another farm. For that to be the case, market-operators and buyers would need to agree that the conservation practices implemented in an agricultural ecosystem credit market program produce the same benefit in an equitable amount, regardless of type of farm or ranch, conservation practice implemented, size of implementation or scope of implementation.

For this discussion, if carbon is to be considered a commodity, two risks need to be addressed. The first is the risk of over-supply. If the number of buyers demanding asset credits is held constant and there is an over-supply of credits due to a large number of farmers and ranchers generating assets, the price per ton of a credit will fall. Farmers may look to store credits until prices rise, but there is little information about how long a credit holds value and how the buyers’ willingness to pay would change if they are asked to pay for credits with benefits that occurred in the past. If low prices are not resolved, the low price will discourage farmers and ranchers from participating in the agricultural ecosystem credit market and fewer participants will find it economically viable to continue participating. If the goal of a market is broad participation, the economic viability of the farm participating will need to be maintained to keep participants from stepping away from the market.

The second risk that needs to be addressed is the price received by the farmer for generating the asset. In a commodity market, every farmer receives the same price for the same commodity as determined by the market it is trading on. Localized prices may differ due to basis risk when the local cash price differs from the futures price in the market, or a price differential may be applied due to the quality of the commodity sold at the elevator. The buyer of the commodity pays that same price to acquire the commodity in bulk before it moves on to the next step in the value-added process. The value-added process takes the raw commodity and turns it into food.

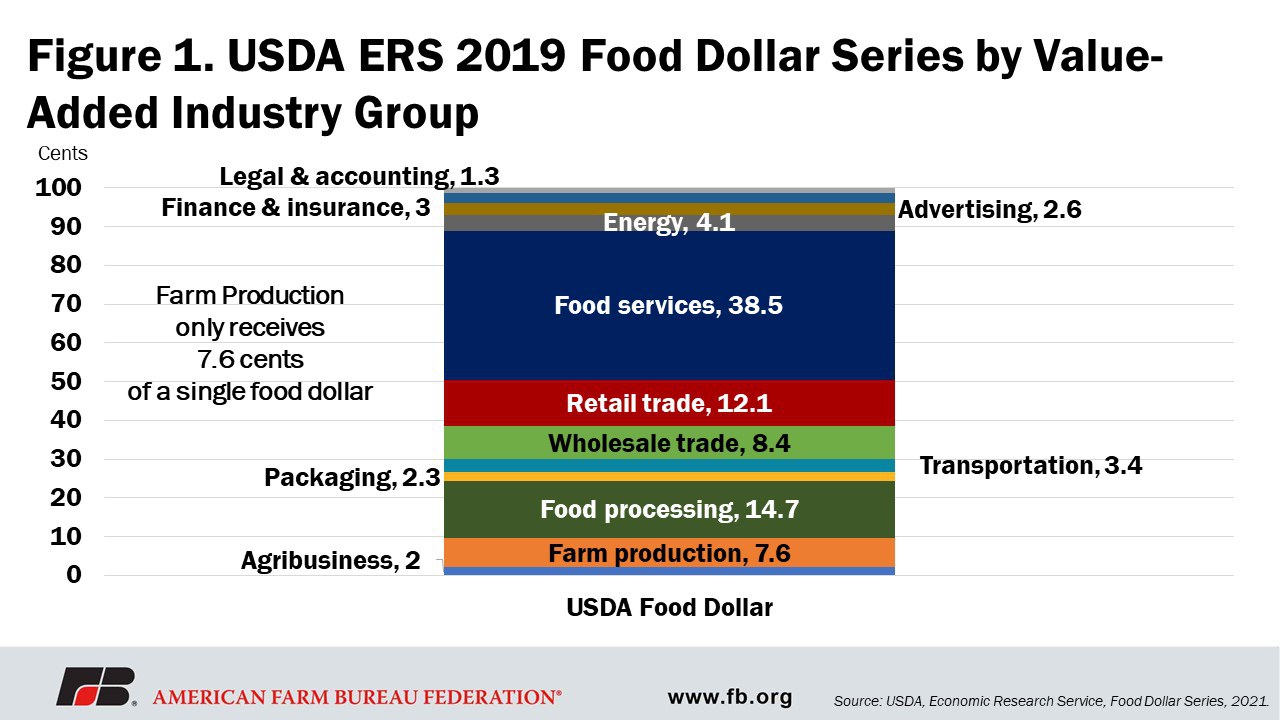

Through its food dollar series, USDA’s Economic Research Service tracks expenditures on each of the various food commodities sold in proportions that represent their share of the annual sales in the U.S. food market. The information is broken down to the share of the food dollar by the input-components used to make it. ERS tracks the contributions of 12 industry groups in their role to bring food to the market. The 12 groups are agribusiness, farm production, food processing, packaging, transportation, wholesale trade, retail trade, food service, energy, finance and insurance, advertising and legal and accounting.

For the 2019 calendar year, the farm production value in the value-added food dollar was 7.6 cents. Agribusiness was 2 cents of the food dollar. Food processing represented 14.7 cents of the food dollar, while packaging represented 2.3 cents. Transportation was 3.4 cents of the food dollar. Wholesale trade represented 8.4 cents and retail trade was 12.1 cents. The food services portion of the value-added food dollar was the largest portion, representing 38.5 cents. Energy was 4.1 cents, with finance and insurance representing 3 cents and advertising at 2.6 cents. Legal and accounting’s share of the food dollar was 1.3 cents. Figure 1 compiles USDA’s value-added food dollar for 2019.

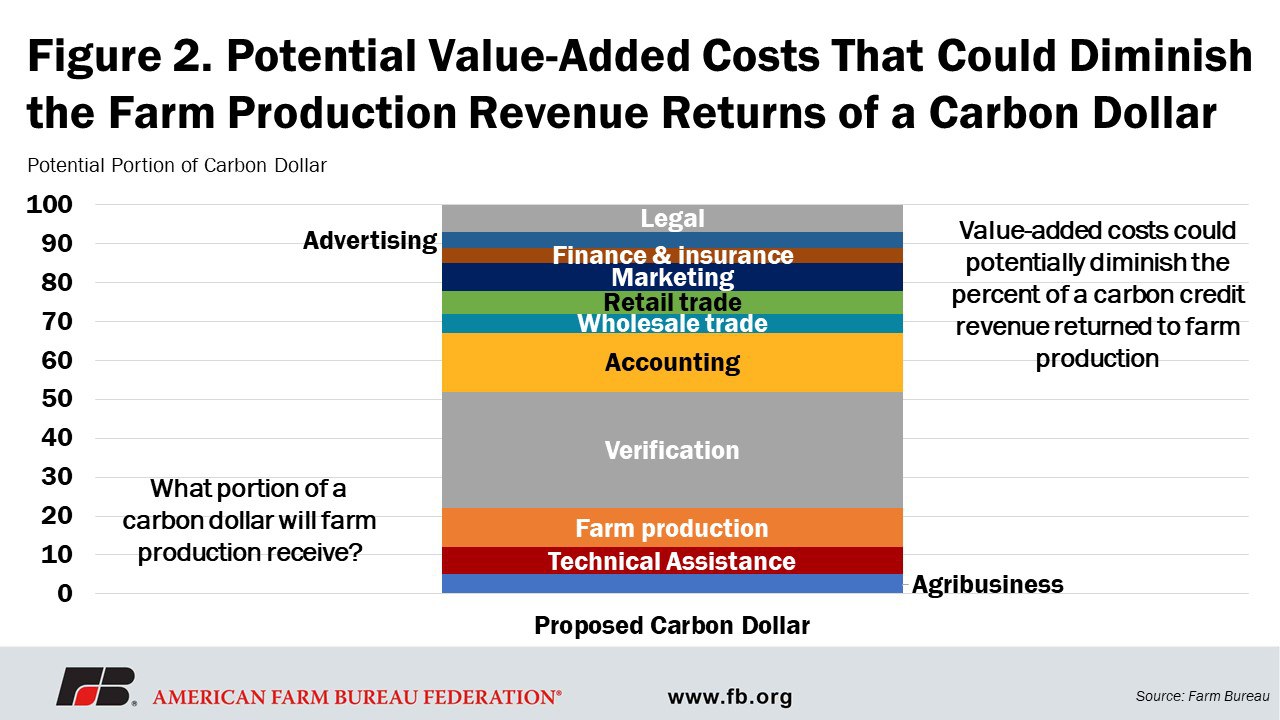

The food dollar example speaks to the share of a purchased commodity’s price that comes back to the farmer. If carbon is treated as a commodity, what share of the purchased carbon credit will come back to the farmer? The input costs and technical assistance consume a portion of the farm production revenue generated for producing a credit. After a carbon credit is produced, we know there are costs associated with verification (i.e., Part 3: Barriers to Participation in Ag Ecosystem Credit Markets). The accounting system required to track and maintain credits in a market, as well as the prevention of double-counting credits across markets, will require an added fee. Not to mention that market-operators could require transaction fees and/or enrollment fees to keep the market staffed and to maintain the infrastructure needed to keep the market operating. There may be wholesale and retail trade that occurs after a credit leaves the farm that would lessen the share returned to farmers. Finance and insurance services, advertising and marketing services, and legal services could decrease farmers’ share of the carbon dollar. The farm production share of the carbon dollar could quickly diminish in the process of generating a carbon asset credit for market purchase the same way the farm production share of the food dollar has decreased with the added costs of bringing the commodity to market. Figure 2 shows potentially how a carbon credit dollar could be portioned out on a percent basis.

Summary

Ultimately, in private markets, the price of an ecosystem credit will be determined by the market-operator. A farmer or rancher can expect to be paid for some portion of the cost it takes to generate the agricultural ecosystem credit, which may or may not include costs like soil sampling and quantification methods, while the buyers could be more likely to bear additional costs for operating the market, such as third-party verification. There are some market risks that could impact the price farmers receive for generating an agricultural ecosystem credit. There is the risk of an over-supply of credits, which could drive down the price farmers receive for generating agricultural ecosystem credits. There is also the risk of a diminishing farm production share of the carbon dollar, similar to the farm production share of 7.6 cents of the food dollar. The market-operator has the final decision on how it structures its operations, which in turn will determine the pricing strategy.

The next and final Market Intel article in this series looks at the development of good business practices in these markets and assesses the long-term impacts of agricultural ecosystem credit markets.

Top Issues

VIEW ALL