Sustainability Markets, Part 3: Barriers to Participation in Ag Ecosystem Credit Markets

TOPICS

SustainabilityShelby Myers

Economist

photo credit: Alabama Farmers Federation, Used with Permission

Shelby Myers

Economist

AFBF’s Market Intel is publishing a five-part series to highlight the opportunities, challenges, policy levers and overall operation of agriculture ecosystem credit markets.

This Market Intel article considers some of the barriers to participate in agriculture ecosystem credit markets that farmers and ranchers could face. Making any kind of change on a farm or ranch creates some kind of cost. Some of those costs are explicit, cash expenses, while others are trade-offs that force a farmer or rancher to give up something in order to participate. All barriers to participation carry risk that weighs differently from farm to farm. More risk-averse farmers may require more tools and support to participate, while those with the financial footing to be riskier could participate with less concern. Every farm and ranch is different, which makes it difficult to estimate how conservation practice adoption will impact the ultimate profit of a farm or ranch.

Explicit Cash Expenses

Explicit cash expense barriers associated with adopting conservation practices come in the form of input costs, variable costs and fixed costs. Input costs include operating costs that require upfront purchases necessary to begin production. These are items such as fertilizer, pesticides, seeds, weaned animals, feed and any other production input. Variable costs are costs that will change depending on the amount of intended production on a farm or ranch and include items like fuel and oil, electricity, labor (hired and custom), repairs and maintenance, water use and storage. Fixed costs are costs that must be paid but are not dependent on the level of production. These include operator labor, machinery, soil testing, taxes, asset depreciation/capital consumption, rent and interest expenses.

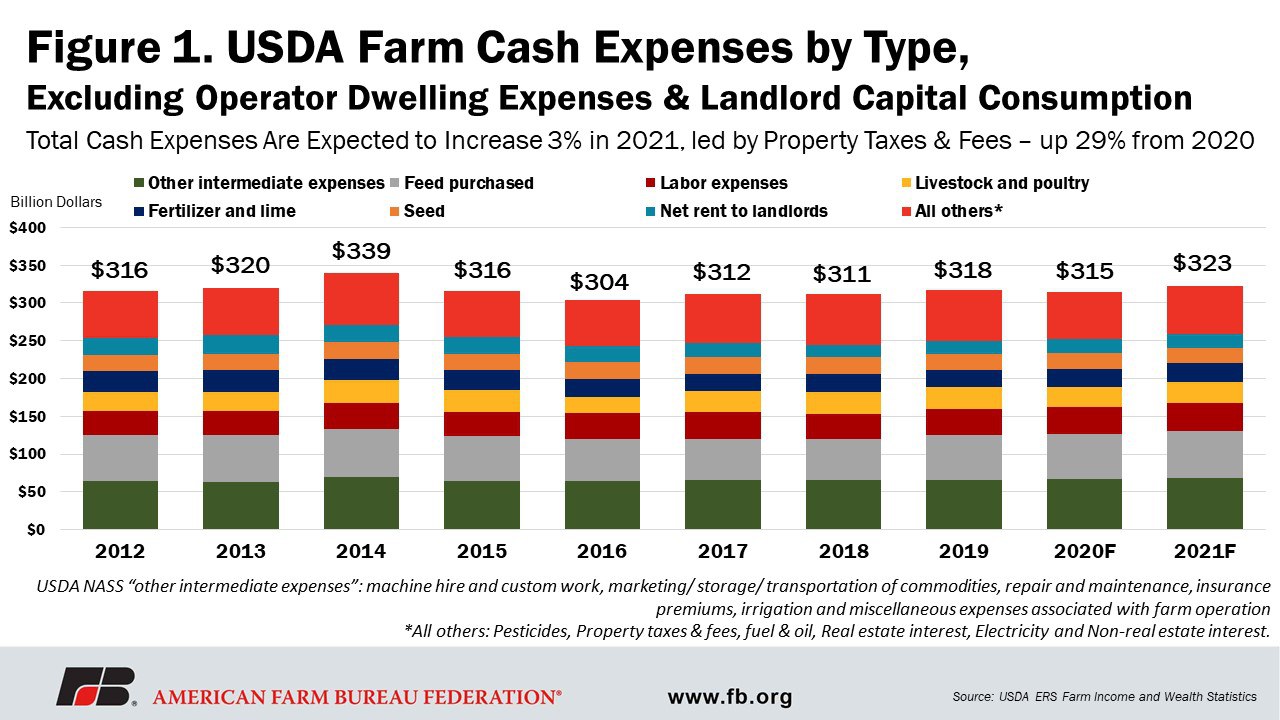

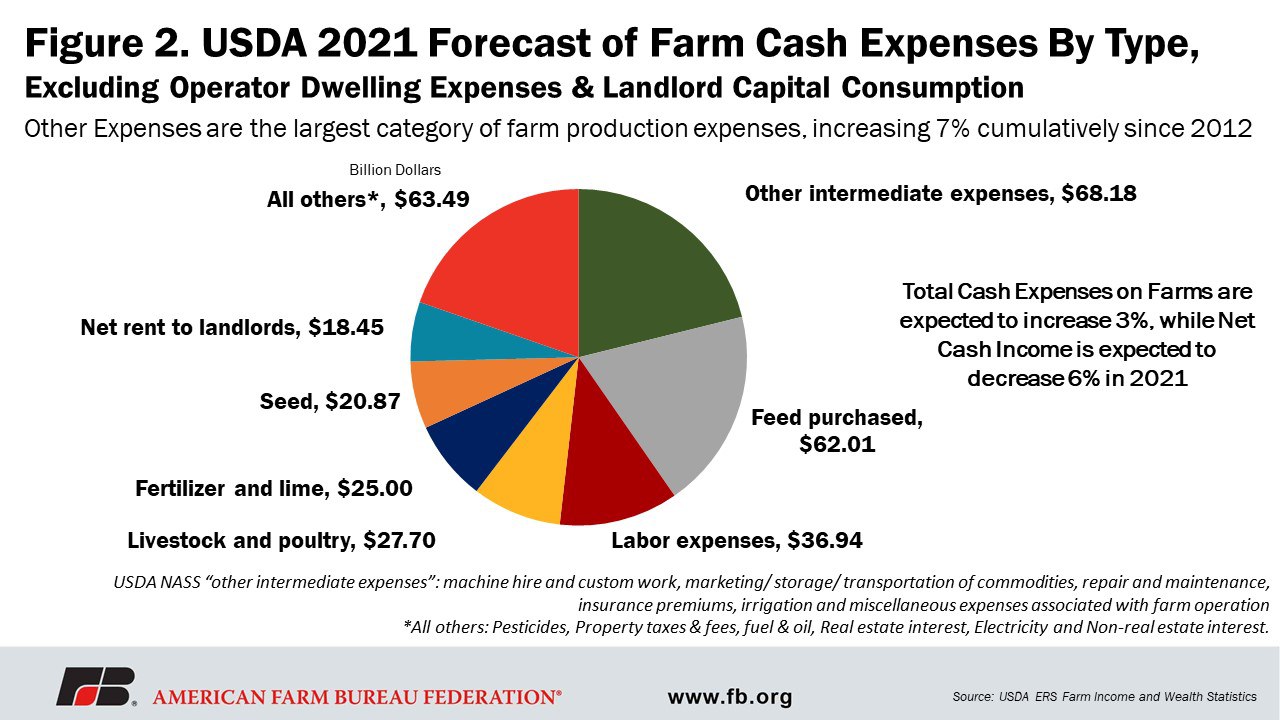

When USDA estimates net cash income, cash expenses include feed purchased, labor expenses, livestock and poultry, fertilizer and lime, crop seed, net rent to landlords, pesticides, property taxes and fees, fuel and oil, interest on real estate and non-real estate, electricity and other intermediate expenses. Those “other intermediate expenses” are the largest category of expenses and tend to be the most difficult to budget for considering they are usually unexpected costs. For example, while you can expect bumps along the way during harvest, it is difficult to estimate and budget for the combine to have a breakdown in the middle of the field and know what the maintenance and repair costs plus labor will be. The “other intermediate expenses” category includes items like machine hire and custom work, marketing/ storage/ transportation of commodities, repair and maintenance, insurance premiums, irrigation and miscellaneous expenses associated with running a farm.

Figure 1 displays USDA-Economic Research Service’s estimates of farm cash expenses, excluding expenses that occur on the operator’s dwelling and landlord capital consumption.

A change to a farm or ranch operation could increase costs associated with the operation, depending on the conservation practice adopted. For example, as reported by farmers experimenting with conservation cropping systems, in a no-till cropping system, expenses spent on machinery and hired labor may be saved -- $10 to $12 per acre and $4 to $15 per acre, respectively -- but more money would be spent on chemicals used to manage weeds that have taken root -- typically $7 to $12 per acre. In a cover crop system, farmers have said increased expenses come in the form of cover crop seed purchases, typically $8 to $15 per acre depending on the mix, and the overall cost to actually plant the cover crop, which would include fuel, labor and any unexpected costs incurred, between $5 to $15 per acre, bringing the total cover crop investment up to $30 per acre. But according to research studies, up to $5 to $14 per acre could be saved in fertilizer or herbicide crop chemicals. The overall investment is more than the return in savings, thus providing some kind of cost-sharing to help offset upfront additional costs could help promote widespread adoption.

These costs are based on how the market and the farm operate today. However, looking down the road, there could be unexpected financial costs that have not been considered. Many of the costs associated with conservation practices are also priced based on market conditions. If cover crop demand increases at current supply levels, there could be an unexpected price increase for cover crop seed. Farming is also very dependent on the weather. Events commonly called “acts-of-God-events” could disturb the soil, or even overall farm operations, and potentially decrease the amount of carbon sequestered or unexpectedly worsen the water quality. This would lower the price a farmer or rancher could expect for the credits they were working to generate for purchase and would not return the revenues expected for participating in an agriculture ecosystem credit market. A risk management tool that can protect the financial investments made annually to participate in these markets and mitigate the risk in the event of an “act-of-God” weather occurrence may encourage more farmers and ranchers to participate.

Figure 2 shows USDA’s forecast of 2021 farm cash expenses by type, with “other intermediate expenses” as the largest cash expense in 2021.

Examples of Trade-off Barriers

Increased costs and financial barriers are not the only concerns farmers and ranchers have about participating in an agricultural ecosystem credit market, as indicated by most anecdotal and peer-reviewed research reports. There are some non-financial trade-offs, though some may have financial impacts. The first is the labor trade-off. While labor may be a lower upfront cost on some farms and ranches or is even just a single person’s income, there is a labor trade-off for conservation practice adoption. Especially during seasonally busy times, such as planting and harvesting, operators have set plans to ensure the necessary work gets done in a timely fashion. Many conservation practices, even those that may be low-cost to implement, simply can’t be accomplished because there aren’t enough people to get the job done or enough money to hire a worker or workers to do it.

Another trade-off is the time required to gain the knowledge to implement some conservation practices, like getting the cover crop mix just right or learning when certain steps of the land conversion need to happen. With that, there is a time trade-off waiting for the benefits of the practice to occur. The available research promotes the benefits of conservation practices but acknowledges the benefits happen over time, not necessarily in the short-term.

There are trade-offs of time, money and expertise consulting with a lawyer when considering whether or not to enroll in an agricultural ecosystem credit market. With the contracts, there is a trade-off of relinquishing some amount of farm data in order to quantify the assets being generated on the farm and put them into a credit. And with all of that, there is a trade-off of time and relationships in securing authority from all the associated parties with an ownership interest of the soil and practices involved. When evaluating whether or not to participate in an agricultural ecosystem credit market, farmers are not only considering the financial barriers but also trade-off barriers.

Verification

A market’s credibility comes from its ability to quantify and verify that the asset generated is legitimate. Many market-operators are relying on third-party verification systems to add a layer of credibility to their market. Regardless of how verification occurs, the bottom line is that verification will be an added cost to market participation. The question becomes, who bears the cost of verification?

Additionality

In the ecosystem credit market space, “additionality” is defined as generating an ecosystem service above what would normally be occurring to determine whether the action has an actual effect compared to the baseline. Additionality barriers come at the rate of practice adoption and at what magnitude adoption occurs and the baseline for measuring adoption benefits.

The rate of adoption and the magnitude of adoption on a farm, or even in a region, can be an impact of additionality. Does the variety of practices adopted in a region increase the benefits over time or can every farm or ranch in an area adopt almost all the same practices? Is there a diminishing marginal return on benefits based on practices? Does a farm or ranch have to add practices to their current system even if they are already incorporating conservation on the farm or ranch?

The last question leads to the barrier of how to establish a baseline. When does the baseline start? Does it begin at the time of sign-up? But what if the farm or ranch is an early-adopter (see below)? Can a baseline be established retroactively? At what point does the market need to start its measuring before it can quantify the assets generated?

Early-Adopters

For decades, farmers and ranchers have been leading the way in promoting soil health, conserving water, enhancing wildlife, efficiently using nutrients and caring for their animals. As illustrated in part two of this series on conservation adoption (i.e., Common Land-Use Practices Under Consideration for Conservation Adoption), a large number of farmers and ranchers have already adopted conservation practices with the goals of improving productivity, providing clean and renewable energy, and enhancing sustainability. In fact, 15% of all farmland is already used for conservation and wildlife habitat. U.S. farmers have enrolled over 140 million acres in certain USDA conservation programs, equal to the total land area of California and New York combined. The 140 million acres does not include the additional millions of acres already enrolled in voluntary or state-led conservation initiatives.

The conservation work already being done by farmers and ranchers should not be discounted just because the progression of technology and market development have rapidly increased. Finding solutions to allow early-adopters to receive equitable benefits of participating in ecosystem credit markets will be important in establishing markets.

Technological Support

Because of the variety of farms and ranches (i.e., soil types, cropping systems, climate, etc.), there are many ways to adopt and apply conservation practices. Innovative research and precision technology have evolved to help make this easier. Systems for getting farm data inputted, analyzed and responsive are ever-improving. For farmers and ranchers to utilize these supportive technologies, and even participate in ecosystem credit market platforms, rural broadband and on-demand applications must be significantly upgraded.

Summary

Many barriers make it difficult for farmers and ranchers to participate in agriculture ecosystem credit markets. Growing a crop or raising livestock requires significant cash to cover the associated expenses. However financial barriers are not the only hurdle to participation. Trade-off barriers such as labor availability, education, legal advice, verification costs, additionality requirements, being an early-adopter, and lack of quality broadband can prevent farmers and ranchers from being able to participate in these markets. While making any kind of change is costly, change also carries various amounts of risk. Some farms are able to extend their risk tolerance to participate, while others may not have the resources, financial or otherwise. While this list may not cover every obstacle a farmer may face trying to participate in an ag ecosystem credit market, the barriers detailed here and others need to be resolved by market-operators or policymakers to encourage broader participation for farmers and ranchers who voluntarily want to participate in these markets.

The next Market Intel article in this series will discuss how ecosystem credits could be priced and purchased.

Trending Topics

VIEW ALL