Specialty Crop Considerations for the Farm Bill

photo credit: Colorado Farm Bureau, Used with Permission

Daniel Munch

Economist

For nearly 100 years, the history of the farm bill largely tracks the history of food production in the United States as the legislation has evolved to meet the needs of farmers and consumers alike. Agriculture’s role in providing food security, and in turn national security, to the United States is more important than ever. And now, work on the next farm bill has started during a period of volatility on every front – political, economic, weather and beyond.

The latest Census of Agriculture from 2017 found the value of farm level sales of fruits, vegetables, nuts and nursery crops, broadly known as specialty crops, totaled $64.7 billion or about 17% of total U.S. agricultural sales and 30% of total U.S. crop sales. This vital segment of the agricultural economy supports over 220,000 farms and provides nutritious, fresh foods for consumers around the globe. Given the wide variety of specialty crops grown and the unique methods utilized in their production, producers that fall into this category generally have fewer effective risk management options than growers of major field crops and require more specialized market promotion, technical assistance and disease and pest management programs. For this reason, the farm bill, which has historically focused on programs for major row crops, has increasingly been used as a mechanism to support specialty crop producers through targeted funding and programs. Despite these improvements, the farm bill still has room for growth in providing these growers the stability they need in an increasingly volatile world.

The Specialty Crops Competitiveness Act of 2004 defines specialty crops as fruits and vegetables, tree nuts, dried fruits, and horticulture and nursery crops, including floriculture. This includes specialty field crops such as dry beans and lentils widely grown in northern plains states like Montana (which contains 35% of national acreage) and North Dakota (which contains 23% of national acreage). California grows the largest share of U.S. fruits, nuts and vegetables (61% of fruit and nut acreage and 45% of vegetable acreage) with Florida and Washington hovering around 5% each of total U.S. acreage of fruits, nuts and vegetables. The USDA also reports that, in 2020, California held the largest share of fruit and nut cash receipts (73%) and vegetable and melon cash receipts (43%). Florida and Washington both had about 7% of vegetable and melon cash receipts in 2020, and 4% and 12% of fruit and nut cash receipts, respectively. Meanwhile, Montana and North Dakota, held about 1% and 2%, respectively, of the total vegetable and melon cash receipts for 2020. The regional concentration of specialty crop production in a small number of states leads to unevenness in political interest across the country. This means issues facing specialty crop growers may not always be prioritized widely, complicating the ability for growers to access programs that fit their operations’ needs.

Specialty crop growers face risk associated with unexpected weather events and disasters, losses due to pests and disease, uncertainty regarding government regulation or credit conditions, uncertainty in price and the ability to find buyers and uncertainty related to human factors such as labor access that may effect their businesses. While all farmers face these risks, the nature of specialty crop production and their associated markets often lead to heightened levels of risk. For instance, many specialty crops are sold in thinner markets than conventional crops, in which the market involves a very small number of buyers or sellers. This means there is less information available to establish prices that reflect actual supply and demand factors, making it more difficult for producers to forecast cash flows. Thinner markets complicate the ability of government and insurance providers to offer actuarily sound products that protect against price risk. This also can make establishing hedging options such as futures markets unfeasible. Additionally, growers may face heightened costs associated with finding new buyers when a single contract or agreement falls through. Not to mention the risk associated with the wide array of specialized production and labor processes utilized to plant, grow, and harvest specialty crops. Unexpected changes to guest worker visa programs like H-2A, which fruit, nut, nursery and vegetable growers heavily rely on, leave businesses uncertain as to whether they will have the labor necessary to operate. State level wage and overtime rule changes further tighten producers’ bottom lines. During 2020, COVID-19 outbreaks that impacted the meat processing sector also raised concerns for employees in harvesting and packing operations needed to process specialty crops, revealing the wide-reaching impacts associated with staffing risk.

Federal Crop Insurance Program (FCIP)

The USDA offers risk management products to crop producers through the Federal Crop Insurance Program (FCIP). Eligible perils covered under FCIP are defined by the USDA to include, “adverse weather conditions (e.g., hail, frost, freeze, wind, drought and excess precipitation), earthquake, failure of the irrigation water supply (if caused by an insured peril), fire, insects, plant disease (except for the insufficient or improper application of pest or disease control measures), wildfire, and volcanic eruption. Crop insurance does not cover damage or loss of production due to the inability to market for any reason other than actual physical damage for an insurable cause of loss.” There are currently four different types of FCIP plans used to insure specialty crops. The first includes yield-based policies such as Actual Production History (APH) and Yield Protection (YP) which allow producers to select a percent of yield to insure based on their yield history and the percent of a Risk Management Agency (RMA) or futures price. Revenue based policies such as Actual Revenue History (ARH) and Revenue Protection (RP) are based on revenues (either historical or expected) and an RMA market reflective reference price or futures price. Dollar plans such as Dollar Amount of Insurance (DOL), Fixed DOL and Tree Based Dollar Amount of Insurance (TDO) are based on the cost of establishing a crop. Lastly, the Whole Farm Revenue Protection (WFRP) programs insure revenue for the entire farm under one policy to protect from eligible losses and is the successor to the previous Adjusted Gross Revenue (AGR) program. Other supplement coverage options are available to producers that may be in regions particularly susceptible to certain losses. For instance, the Hurricane Protection-Wind Index (HIP-WI) Endorsement covers a portion of a deductible when a county or adjacent county falls within an area of sustained hurricane-force winds.

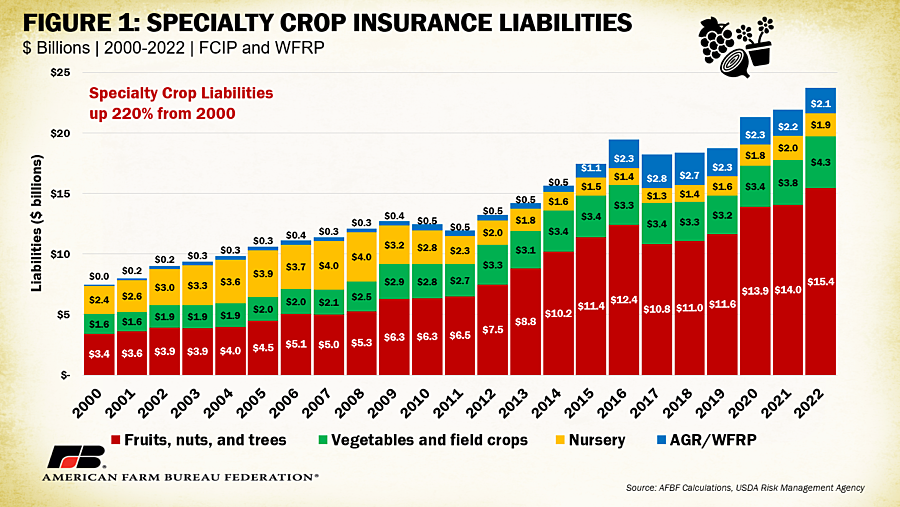

The RMA currently offers 76 different crop insurance policies for specialty crops generally available in the primary regions where they are grown. In 2022, total specialty crop liabilities under FCIP and WFRP programs reached nearly $24 billion, a 220% or $16 billion increase from 2000 and an 8% or $1.8 billion increase from last year. By category, fruits, nuts and trees have experienced the highest numerical increase in liabilities since 2000 with a $12 billion jump or 350% increase. Liabilities through the AGR/WFRP program saw the largest percentage increase over the same period (+22,300%) an increase of $2 billion which may cover more than just specialty crops on a specific operation. During this 22-year period, nursery liabilities under FCIP programs declined by 19% or about half a billion dollars while vegetable and specialty field crop liabilities increased 165% or $2.6 billion. Specialty crop producers, apart from nurseries, have insured more value under FCIP. Notably, while the value of specialty crop liabilities has jumped, the number of policies sold has hovered between 114,000 and 119,000 since 2005 with no clear associated increase—perhaps, linked to market trends that have pushed for a smaller number of larger farms. This means that farms are likely expanding in size and insuring more value instead of insurers increasing sales of new policies to additional farms.

As expected, states with a high prevalence of specialty crop production hold a high frequency of FCIP policies sold. In 2022, California leads the pack with nearly 23,000 active specialty crop FCIP policies sold with almonds (5,057 policies), grapes (4,451 policies), oranges (1,715 policies) and walnuts (1,552 policies) taking the top four spots in the state. North Dakota followed closely in second place with almost 23,800 active specialty crop FCIP policies sold with sales overwhelmingly linked to dry pea (11,893 policies) and dry bean (10,262 policies) production. Alaska held the fewest sold specialty crop FCIP policies with three dry pea plans.

Noninsured Crop Disaster Assistance Program (NAP)

While the FCIP provides a wide array of policies, it falls short in addressing the 350+ unique specialty crops grown and in providing adequate risk protection for producers across every region of the country. Crop producers not covered through FCIP may qualify under the Noninsured Crop Disaster Assistance Program (NAP) which is administered through USDA’s Farm Service Agency (FSA) and has permanent authority under Section 196 of the Federal Agricultural Improvement and Reform Act of 1996. It receives funding as necessary from USDA’s Commodity Credit Corporation which has a line of credit with the U.S. Treasury to fund certain farm programs.

USDA defines NAP eligible crops as any commercial crops grown for food, fiber or livestock feed for which there is no CAT coverage available under the federal crop insurance program, with limited exceptions. These crops include mushrooms, floriculture, ornamental nursery, Christmas trees, turfgrass sod, aquaculture, honey, maple sap, ginseng, and industrial crops used in manufacturing or grown as a feedstock for energy production, among others. Trees grown for wood, paper, and pulp products are not eligible. NAP applicants pay an administrative fee of the lesser of $325 per crop or $825 per producer per county without exceeding a total of $1,950 for farms that cross counties.

To receive a NAP payment, a producer must experience at least a 50% crop loss caused by a natural disaster or be prevented from planting more than 35% of intended crop acreage. For any losses in excess of the minimum loss threshold, a producer can receive 55% of the average market price for the covered commodity. Buy-up coverage may be purchased at 50%-65% in 5% increments of established yield and 100% of average market price, contract price, or other premium price. In 2020, 32% of NAP applications included buy-up coverage while 82% of FCIP liabilities had some form of buy-up coverage. The low share of NAP buy-up coverage is thought to be linked to the passage of the 2018 farm bill. The USDA has said that, though the 2014 farm bill introduced buy-up coverage originally (for crop years 2015-2018), it was made permanent in the 2018 farm bill. Since the 2018 farm bill did not pass in time to reinstate the option during sign up only catastrophic levels were available until May 2019 for crop years 2019 and 2020. After the bill passed FSA allowed producers to retroactively obtain buy-up coverage, but by that time many growers already knew whether they would suffer losses and didn’t choose to buy-up.

Premiums are equal to 5.25% times the producer’s share of the crop, eligible acres, the approved yield per acre, the coverage level, and the average market price. Farmers who qualify as beginning, limited-resource, socially disadvantaged, or veteran farmers may qualify for a service fee waiver or premium reduction. NAP users are subject to an annual payment limit of $125,000 per person for catastrophic coverage and $300,000 for buy-up coverage. A producer is ineligible under NAP if the producer’s total adjusted gross income (AGI) exceeds $900,000.

In 2020, the USDA reported that even though NAP applications covered over a 147 types of specialty crops, farmers in about 40% of U.S. counties did not submit specialty crop NAP applications between 2015 and 2020. New York, Puerto Rico and North Carolina had the most total NAP applications in 2020, each with more than 5,000. NAP is most often used by non-specialty crop growers, with specialty crop applications making up between 25% and 38% of the total between 2015 and 2020 (between 57,000 and 95,000 total specialty crop applications).

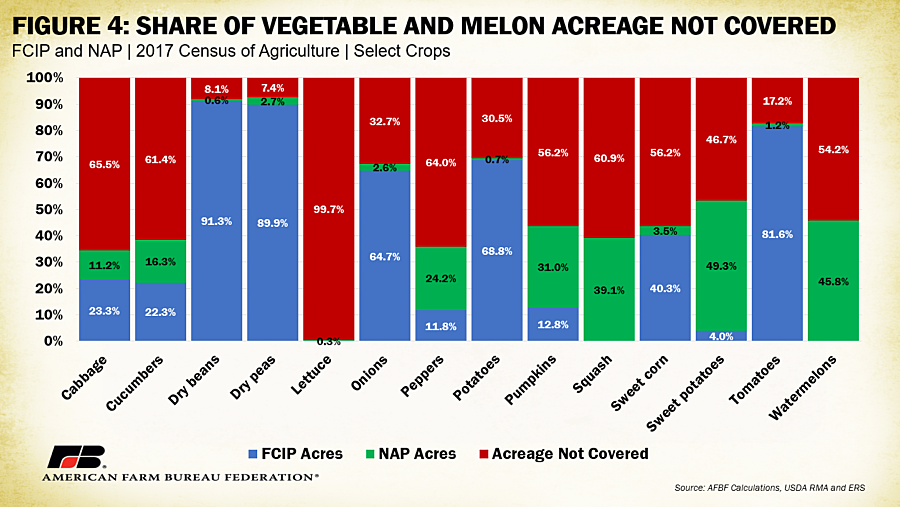

Covered acreage varies from crop to crop. For crops with FCIP offerings the share of acres covered by NAP is often lower than the share covered by FCIP. For growers in areas where FCIP is not offered, NAP provides protection to a significant portion of acreage. RMA does not currently offer FCIP policies for hazelnuts, kiwifruit, lettuce, squash, watermelons, and most leafy greens/herbs/spices/root crops making many of these producers heavily reliant on NAP coverage. Alternatively, many of these crops may be left uninsured. NAP only provides protection against production losses due to natural disasters, not revenue losses, which can make the coverage less helpful to growers of crops that face lower weather risk. This leaves many gaps in the ability for specialty crop growers to effectively manage risk not faced by growers of conventional row crops. Figures 3 and 4 display the share of fruit, nut, vegetable and melon acreage not covered (and covered) by FCIP and NAP by crop using 2017 Census of Agriculture data.

For the listed fruit and nut varieties an average of 43% of acres remain uncovered through FCIP or NAP. For the listed vegetables this average uncovered share moves to 47%. Over 80% of the acreage of hazelnuts, kiwifruit, strawberries and lettuce remains uncovered. Over 20% of cherry, pepper, pumpkin, squash, sweet potato and watermelon acreage relies on NAP coverage. Even with this analysis of a small subset of specialty crop varieties the magnitude of risk that remains for specialty crop producers is revealed. The lack of data and information in thinly sold specialty crop markets remains a strong barrier to the design of effective products, especially those outside the scope of direct disaster losses.

Speaking of disaster losses, given the gaps in existing risk management offerings for specialty crop growers via FCIP and NAP, ad hoc disaster assistance has often been utilized as a means for producers to fill those gaps. However, ad hoc disaster programs require frequent congressional authorization and lack uniformity and timeliness in producers’ abilities to benefit. They often overlook many causes of losses or qualifying provisions necessary to benefit these more vulnerable growers. Refer to a previous article, Revisiting Disaster Programs in the Farm Bill , for background information regarding ad hoc disaster assistance and farm bill authorized disaster assistance programs including the Tree Assistance Program (TAP) which makes payments to qualifying orchardists and nursery tree growers to replant or rehabilitate trees, bushes and vines damaged by natural disasters.

Title X: Horticulture

Title X, the horticulture title of the 2018 farm bill, contains many programs administered by USDA that support specialty crop producers as well as USDA-certified organic agriculture production. The USDA has summarized select provisions in Title X and other titles of the 2018 farm bill that support specialty crop and USDA-certified organic growers. This summary of 2018 updates is provided below:

- Specialty Crop Market News Allocation. Reauthorizes program supporting market data collection. Authorizes $9 million annually in appropriations through FY2023. (§10101)

- Specialty Crop Block Grants. Reauthorizes program and provides mandatory funding of $85 million annually, with funding for multi-state project grants. (§10107)

- Agricultural Trade Promotion and Facilitation. Consolidates into a single program USDA’s four market development and export promotion programs, including the Market Access Program and the Technical Assistance for Specialty Crops program, among others. (§3201)

- Federal Crop Insurance, Specialty Crops. Requires the Federal Crop Insurance Corporation to designate a specialty crops liaison in each regional field office and provide contact information to specialty crop producers. (§11105)

- Specialty Crop Research Initiative. Reauthorizes mandatory funding of $100 million annually through FY2023 and makes other program changes. (§7305)

- Emergency Citrus Disease Research and Development Trust Fund. Establishes a trust fund to extend support for emergency research and extension involving citrus disease. Provides annual mandatory funds of $25 million. (§12605)

- Citrus Disease Subcommittee. Extends the citrus disease subcommittee through FY2023 and changes the composition of the subcommittee. (§7104)

- Acer Access and Development Program. Reauthorizes appropriations of $20 million per year through FY2023 to promote the domestic maple syrup industry. (§12501)

- Marketing Orders. Requires imported cherries and pecans to comply with marketing order grade, size, quality, and maturity provisions or comparable restrictions. (§12503)

- Purchase of Fresh Fruits and Vegetables for Distribution to Schools and Service Institutions. Extends the requirement that USDA purchase additional fruits, vegetables and tree nuts for use in domestic nutrition assistance programs. (§4202)

- Labeling Exemption for Single Ingredient Foods and Products. Allows that the nutrition facts label of any single-ingredient sugar, honey, agave and syrup, including maple syrup, bear the declaration “Includes Xg Added Sugars.” (§12516)

- Organic Certification. Makes changes intended to enhance enforcement and limit program fraud and increases funding for technology upgrades. Amends the eligibility and consultation requirements of the standard-setting board. (§10104)

- Organic Production and Market Data. Reauthorizes mandatory funding of $5 million annually. (§10103)

- National Organic Certification Cost-Share Program. Reauthorizes mandatory funding, rising to $8 million annually in FY2022-FY2023 to remain available until expended. (§10105)

- Organic Agriculture Research and Extension Initiative. Reauthorizes program and increases mandatory funding, rising to $50 million annually in FY2023. (§7210)

Further information on trade specific programs addressed within the farm bill can be found in a previous article: Revisiting Agricultural Trade and Food Assistance Programs in the Farm Bill

Conclusion

Specialty crop producers face a unique set of risks not widely experienced in conventional row crop production. The general lack of reliable market information for the many varieties of fruits, nuts, vegetables and nursery plants acts as a barrier to establishing effective risk management options. Even with a growing number of programs through the FCIP and the addition of NAP, a large percentage of specialty crop acreage remains uninsured. This shifts pressure to ad hoc disaster assistance programs which have their own set of gaps and lack actuarial soundness. Not to mention, the specialized labor demands, production practices, pest and disease management techniques and marketing approaches needed in a successful specialty crop operation calls for targeted support programs. The farm bill has increasingly addressed issues facing specialty crop producers in Title X. Over recent decades, more program supporting specialty crop producers have been created. As discussions ramp up for the 2023 farm bill, it is important to consider the unique market challenges facing specialty crop producers and the current farm bill provisions in place to make informed future recommendations.

Much of the above information is based on summaries provided by the Congressional Research Service and by the USDA in their recent report: Specialty Crop Participation in Federal Risk Management Programs.

What We're Saying

Specialty Crops Need Economic Aid

Jan 6, 2026

READ MORE

USDA Announces Payment Rates for Farmer Bridge Assistance Program

Jan 6, 2026

READ MORE

Farm Bureau Recaps Challenges and Successes of 2025

Dec 17, 2025

READ MORE

Farm Relief Payments Bring Needed Support, but Gaps Remain

Dec 10, 2025

READ MORE