Rising Fuel Costs Continue to Impact Farmers

TOPICS

Market IntelShelby Myers

Economist

photo credit: Getty

Shelby Myers

Economist

Like all Americans, farmers and ranchers are facing higher prices at the pump, as well as on the farm. Growers have been facing these price increases throughout the spring as they work to plant during one of the most important crop years in recent history. Growers have expressed concerns about the availability and delivery of diesel fuel when they need it most, especially as they have faced delayed planting in many areas. The window to plant crops this year was smaller than usual, so fuel delivery needed to be timely, but it also was very expensive.

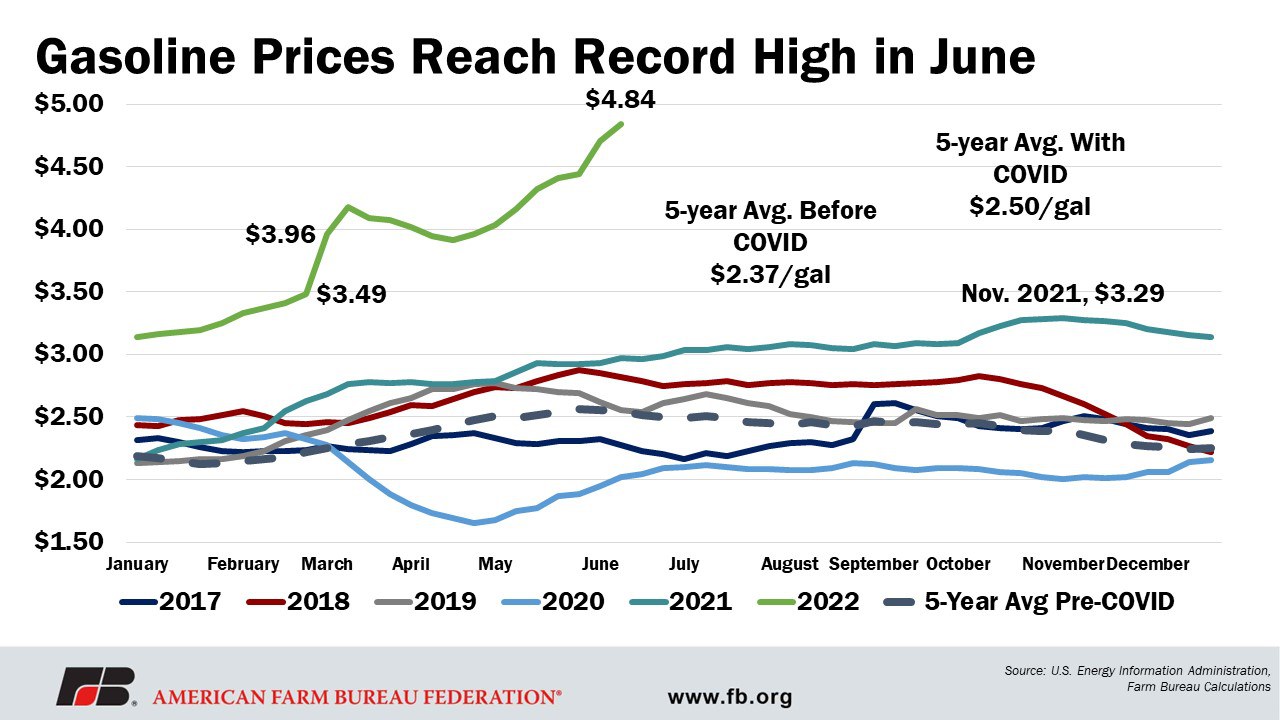

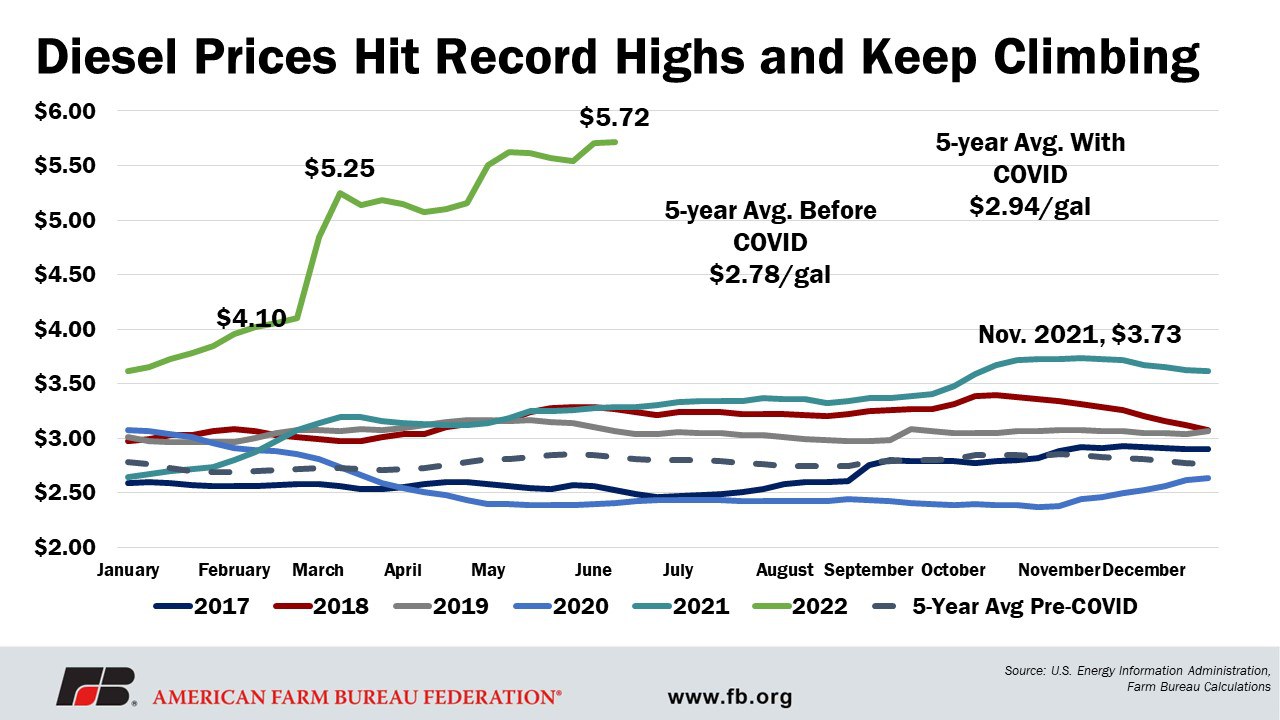

Gasoline prices hit a new high, rising above $5.006 in June, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration. This is up $1.937 per gallon, 63% higher than the same week in June 2021. This new high price of gasoline is nearly two times higher than the five-year average price of gasoline before 2020 when COVID lockdowns pushed gasoline demand way down. Diesel prices rose to $5.718 per gallon in June, up $2.432 per gallon, or 74%, compared to $3.286 per gallon in June 2021. The current high price of diesel is more than two times the price paid before 2020. Looking back to the end of February 2022, when Russia invaded Ukraine, the price of diesel jumped by $1.15 per gallon within the two weeks following. Before Russia’s actions, diesel prices were still rising, but were barely $4 per gallon and had sat around $3.60 per gallon as 2021 closed.

So why are gas and diesel so much more expensive now than just a few months ago or even a year ago?

Factors Increasing Fuel Costs

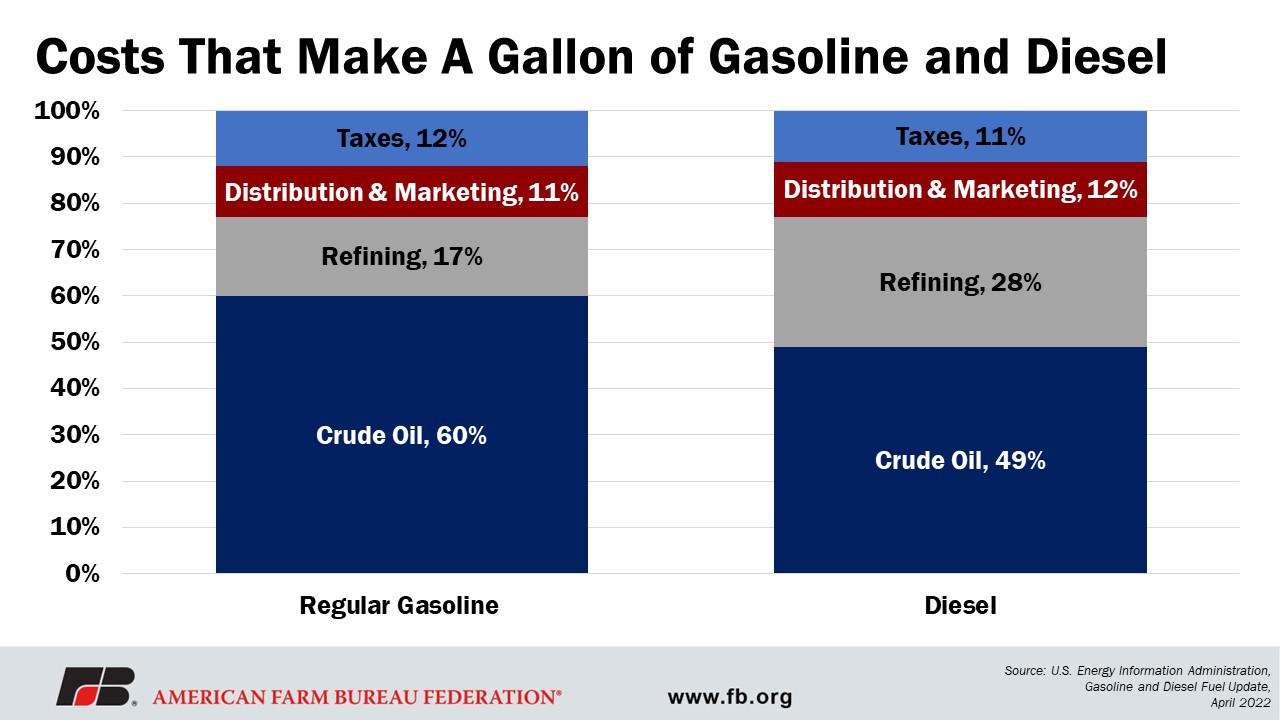

The U.S. Energy Information Administration breaks down the costs within a gallon of fuel. As of April 2022, the most recent data available, 60% of the cost of regular gasoline is crude oil, 17% is the cost to refine, 11% is costs associated with distribution and marketing, and 12% is taxes, which vary based on the state in which you are pumping gasoline.

In April 2022, the cost of diesel, the primary fuel option for farmers and ranchers, was also made up of four parts – 49% is based on crude oil, 28% is refining, 12% is costs associated with distribution and marketing and 11% is taxes, which varies by state.

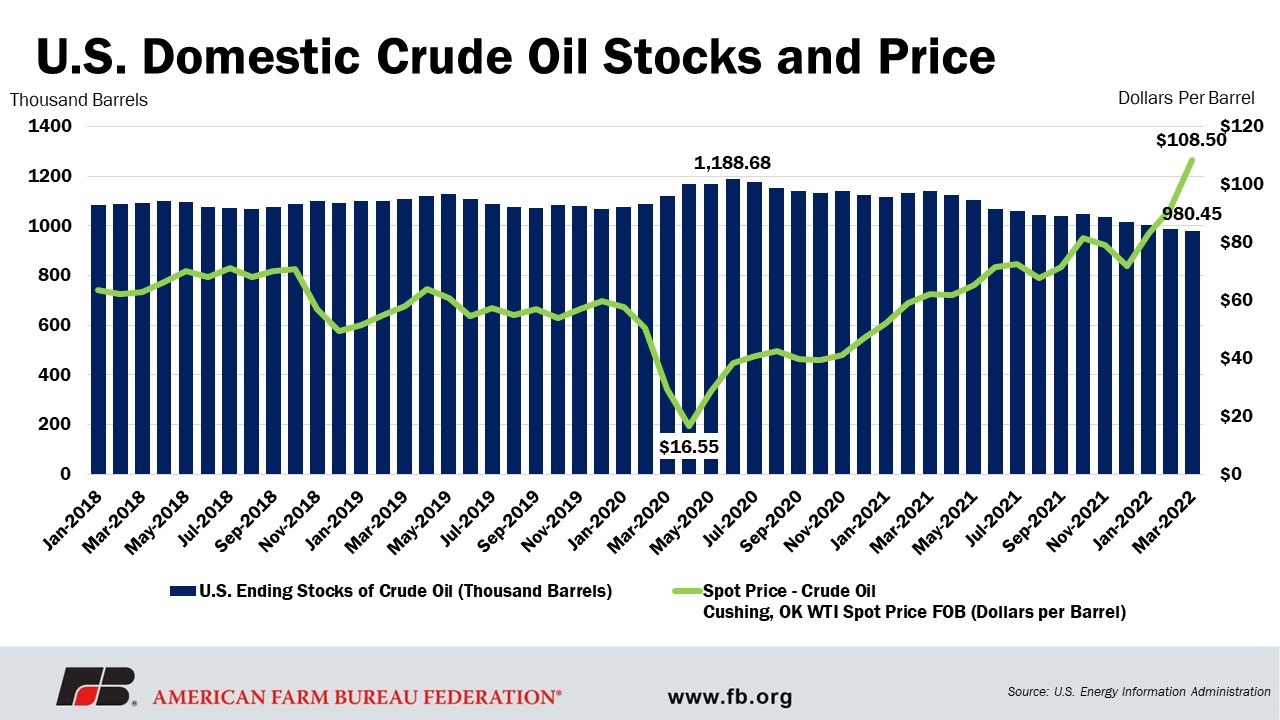

As shown, the price of crude oil is the largest contributing factor in the price of a gallon of gas. Diving deeper into the crude oil market, obviously, supply and demand play a significant role in setting the price of crude oil, especially since crude oil is a commodity.

Supply of Crude Oil

The U.S. supply of weekly crude oil stocks, similar to ending stocks of corn or soybeans, is at its lowest point since 2004, meaning there is less supply on hand. And weekly ending stocks of regular motor gasoline are down 16% compared to the same first week in June last year, moving from 258.661 million barrels a year ago to 218.184 million barrels. U.S. diesel inventories are down 21% compared to the same first week in June last year, lowering from 137.214 million barrels to 108.984 million barrels. It’s important to note that in the U.S., it is normal for inventories to decline in the spring and summer months due to increased demand from road travelers.

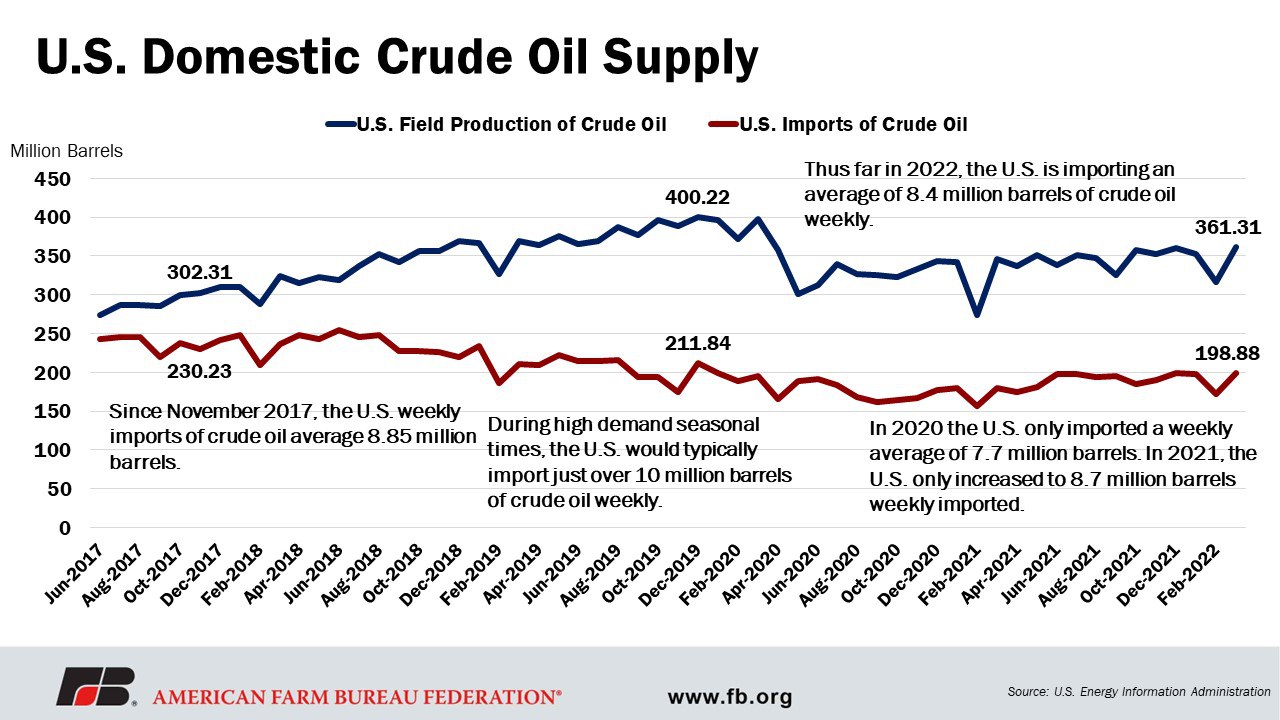

The U.S. was at peak monthly production of crude oil in December 2019, producing just over 400 million barrels. In March 2022, the U.S. was producing just over 361 million barrels for the month. The U.S. has only just begun consistently producing over 300 million barrels monthly since November 2017 and in the past four years has only dipped below 300 million barrels in February 2018 and February 2021.

We continue to see evidence of the U.S. economy trying to play catch-up to production slowdowns and interruptions created by COVID-19, with additional hurdles, like Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, impeding supply from catching up with demand.

Since the U.S. started domestically producing over 300 million barrels monthly in November 2017, U.S. weekly imports of crude oil have averaged 8.85 million barrels. During high-demand seasonal times, the U.S. would typically import just over 10 million barrels of crude oil weekly, but imports have been declining as a result of the 2020 COVID lockdowns, when demand dropped and imports followed suit, with the U.S. only importing a weekly average of 7.7 million barrels. In 2021, U.S. imports increased slightly to 8.7 million barrels weekly. Thus far in 2022, the U.S. is importing an average of 8.4 million barrels of crude oil weekly.

Demand of Crude Oil

While the U.S. is relatively behind its normal domestic production of crude oil and limited imports are causing supplies to be short, demand is rising, both domestically and globally. As noted, mid-March through the end of September is the peak demand time for gas and diesel, so it is normal for inventories to lower during this time. What makes the situation difficult this year is that the U.S. does not have the same quantity of additional supplies, like imports, to supplement the increased demand.

The East Coast, in particular, will continue to see fewer imports. In addition, East Coast ports are likely to have an increase in exports as the U.S. supplements demand from European and Latin American countries that would normally secure supplies from Russia.

This dynamic, however, is creating a market force that puts U.S. consumers at a disadvantage. Crude oil, gasoline and diesel are all considered global commodities. Global market forces in the short-term are incentivizing suppliers to sell off inventory at the cash price today, rather than the lower posted future price. This creates a disincentive for suppliers to hold back any inventory that would likely move through domestic channels, thus shortening domestic U.S. supplies. It has been reported that the spread between current and future prices has been as much as $1 per gallon. This would mean that suppliers would lose as much as $1 per gallon if they were to hold on to inventory for 30 days or more.

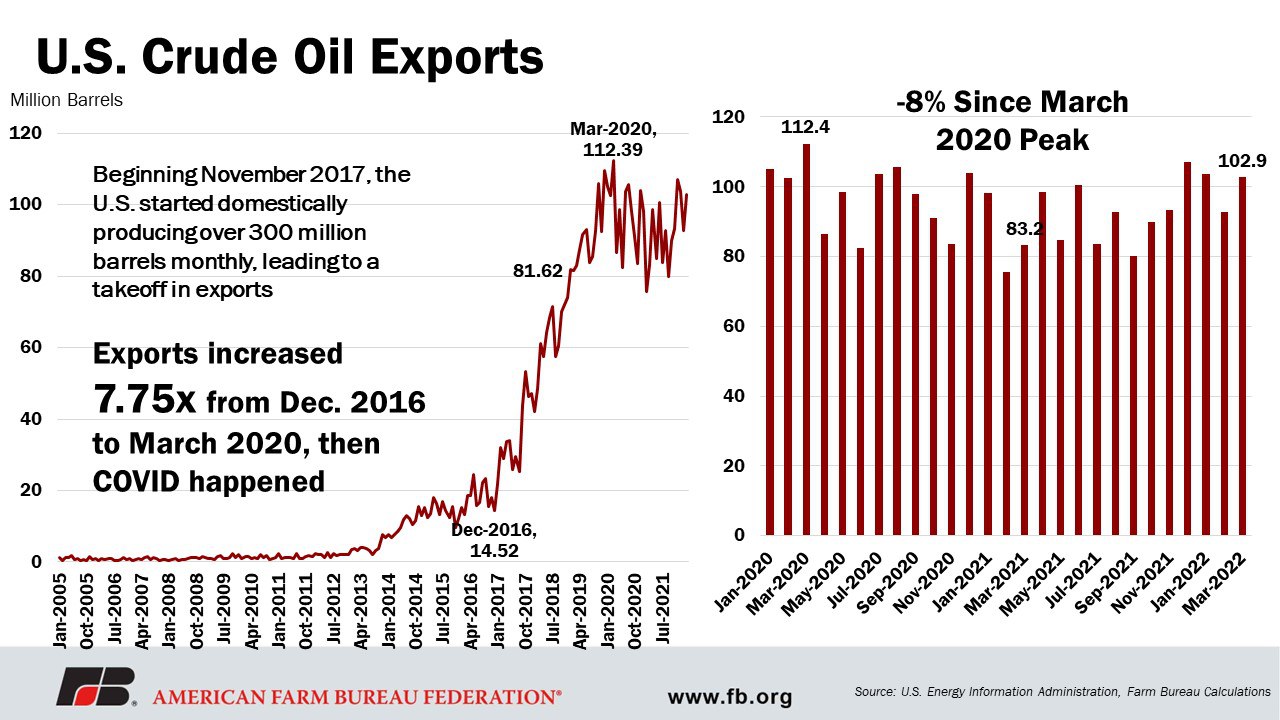

The most recently reported data for U.S. exports of crude oil says the U.S. exported nearly 103 thousand barrels of crude oil, about 8% behind the U.S. peak export quantity in March 2020. Year-over-year comparisons show the U.S. exported about 24% more crude oil in March 2022 compared to March 2021, however, in March 2021 the U.S. was exporting about 26% less crude than in March 2020. As the U.S. ramped up domestic production in the beginning of 2017 to reach the point of consistently producing over 300 million barrels monthly, U.S. crude oil exports took off, multiplying by nearly 7.75 times the quantity the U.S. was exporting in December 2016.

The Bottom Line for Farms

Fuel prices have risen sharply since Russia invaded Ukraine, and high fuel prices continue to add to the conversation of high input prices for all agricultural producers. In 2020, fuel represented about 3% of total on-farm expenditures. Earlier this year, USDA expected fuel costs to increase more than 2% as part of net farm income projections compared to the cost of fuel in 2021 and we expect that increase to be larger when USDA updates those numbers in September. Since 2013, fuel has increased as a farm production expenditure cumulatively by 3%.

This expectation comes with the latest USDA cost of production data, which estimates that the cost of fuel, lube and electricity combined is projected to increase 34% in 2022 compared to 2021, after just a slight cost reduction, decreasing 1% from 2020 to 2021. A glimmer of hope for farmers is USDA’s estimate that the price of fuel may decrease about 18% in 2023 compared to 2022, but these projections are very early and there is significant uncertainty.

It is getting more costly to farm and while some – not all – commodity prices have increased, farmers are not necessarily making more money. In fact, with higher expenses, many farmers and ranchers are concerned they will not be able to break even, let alone make any kind of profit. And, if the market takes an unexpected turn that pushes commodity prices lower, farmers will likely not be able to make enough revenue to cover these high production costs.

Beyond the farm, diesel and gasoline are used to transport farm products to and from the farm. The rising cost of diesel and gasoline will inevitably increase the cost of the food consumers buy at the grocery store.

Summary

The rising price of fuel and other inputs – with no end in sight – weighs heavily on farmers and ranchers. For diesel and gasoline, crude oil supply and demand fundamentals are pushing prices up at the pump. If the U.S. cannot increase production and is not importing the supplemental quantities needed to meet the increased demand, prices could continue to rise. Furthermore, limited domestic refining capacity for those crude oil supplies could further strain supply availability as demand rises, which could also contribute to increased costs. It will be important to keep an eye on domestic production to see if the U.S. can return to its peak production level of nearly 400 million barrels a month. To do this, two things need are needed. First, domestic crude oil production companies must have regulatory flexibility and second, refiners need a business environment that fosters certainty and increases domestic capacity to deliver. The upcoming hurricane season could also impact diesel supplies, especially if any of the hurricanes hit areas that refine diesel or contribute to offshore production. Given that the U.S. is in a very supply-sensitive market, any one misstep could drive fuel prices even higher.

Trending Topics

VIEW ALL