Revisiting NAFTA: The Way it Could Be

photo credit: Robert Couse-Baker / CC BY 2.0

Veronica Nigh

Former AFBF Economist

Implications

For a few hours Wednesday, April 26, the trade world was on edge based on press reports the president was considering signing an executive order withdrawing the United States from the North American Free Trade Agreement. By late that evening, the immediate concern of exiting NAFTA had passed after President Donald Trump announced: "It is my privilege to bring NAFTA up to date through renegotiation.” The scare prompted many to wonder out loud however what tariffs the United States would face in Mexico and Canada if NAFTA was not in effect. Because of the transparency the World Trade Organization brings to international trade, we already know.

Most Favored Nation Tariffs on Agricultural Goods

In nerdy trade speak there are three categories of tariffs countries apply to trade with one another. The first category is for those nations not part of the WTO. These tariffs tend to be the highest of the three categories. The U.S. is a member of the WTO and is not subject to these higher tariffs when trading with the other 163 nations that belong to the WTO.

The second category is what’s known at Most Favored Nation tariffs. These are the maximum allowed tariff rates WTO members have committed to charge on imports from other WTO members. WTO members are allowed to charge lower rates below their bound commitments, but they cannot charge more. Countries can change applied tariff rates at any time, with little prior notice, as long as they are below the bound tariff rates.

The third category is preferential tariffs, which are negotiated under free trade agreements between specific countries. Under these agreements, a country promises to give another country's products lower tariffs than their MFN rate. As result of NAFTA, the U.S., Canada and Mexico have reduced the tariffs to zero for most products entering their countries from the other members.

With that background in mind, if the U.S. were to leave NAFTA the preferential tarrif rates would no longer apply. Instead U.S.-producer agricultural commodities (and other exportable products) would face higher MFN tariff rates. Mexico and Canada have very different tariff profiles when it comes to MFN tariff rates. The MFN tariff schedule for each country is reviewed below.

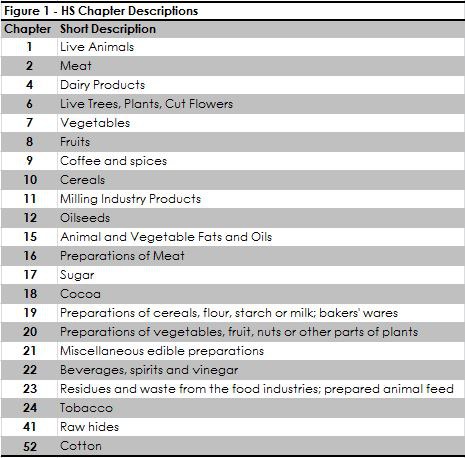

A systematic way to compare across the countries is to utilize the World Customs Organization’s internationally agreed Harmonized System at the sub-heading (HS6) level. Under the HS system, the broadest categories of products are identified by two-digit chapters (e.g. 07 is edible vegetables and certain roots and tubers). These are then sub-divided by adding more digits: the higher the number of digits, the more detailed the categories. For example the four-digit code or heading 0703 is a group of products that includes onions, shallots, garlic, leeks and other alliaceous vegetables, fresh or chilled. The sub-heading 070310 is onions and shallots, while 070320 is garlic. A short description of each chapter is included below in figure 1; a full description can be found on the United States International Trade Commission website.

Share of Lines with Tariffs above Zero

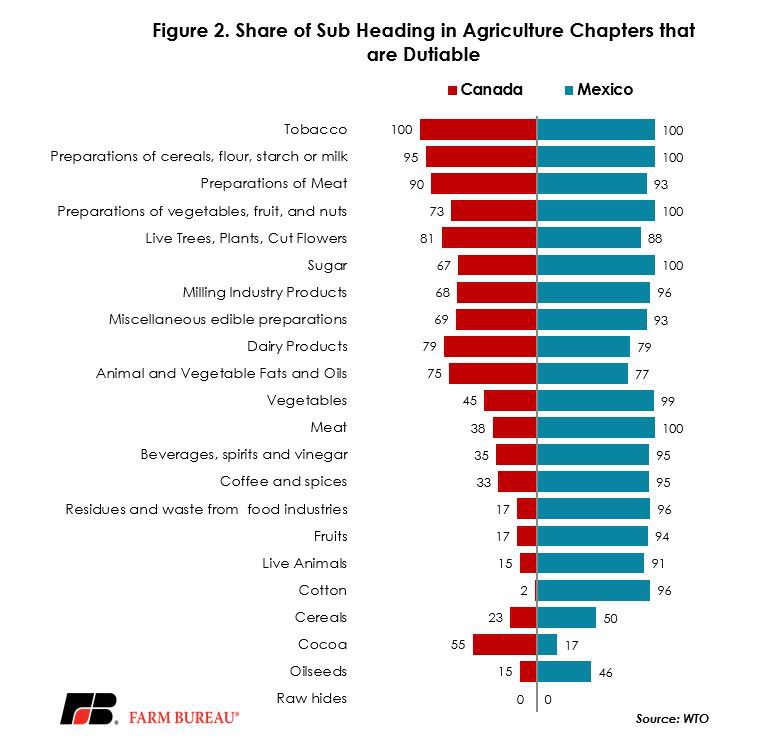

Mexico still has large shares of agricultural chapter sub-headings with tariffs above zero. Figure 2 highlights that in 15 of the 22 chapters, 90 percent or more of the sub-headings still have taxes on imports. This includes a number of chapters very important to U.S. agricultural trade – live animals, meats, vegetables, prepared foods and cotton.

A significantly smaller share of agricultural chapter sub-headings is subject to tariffs above zero in the Canadian market. Figure 2 highlights that in only 3 of the 22 chapters, are 90 percent or more of the sub-headings facing import taxes. For anyone with knowledge of the makeup of Canadian agriculture, they should come as no surprise; dairy (chapter 4), live trees and plants (chapter 6) and animal and vegetable oils (chapter 15).

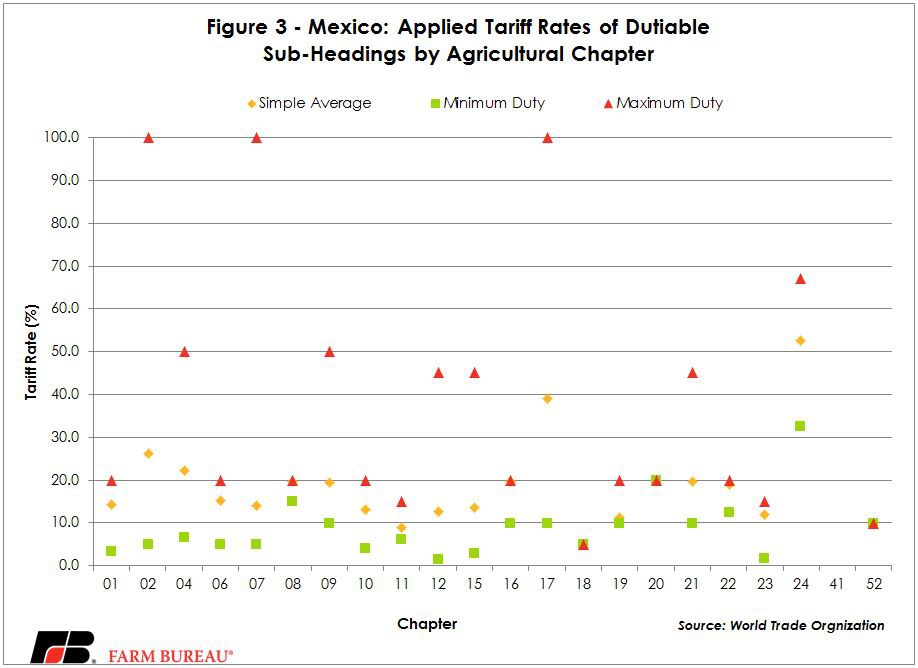

Mexico

In figure 3 we notice that not only are many tariff lines still in effect, but those import taxes can be quite significant. For example, the simple average applied tariff on taxable lines within chapter 2 – Meats in 2016 was 26.4 percent. However, this average is quite misleading, as the range of tariffs within chapter 2 is quite wide. For example, in 2016, almost all fresh, chilled or frozen chicken, with the exception of livers, faced applied tariffs of 100 percent. Meanwhile, the applied rates for beef (fresh or chilled) and pork (fresh, chilled or frozen) were 20 percent. At the lower end of the scale, sheep and goat meat, fresh, chilled or frozen were subject to a rate of 10 percent. Clearly, this is a case where details matter, but averages can be helpful to appreciate the relative difference between large categories of products. Eleven of the 22 chapters have average tariffs that exceed 15 percent.

Canada

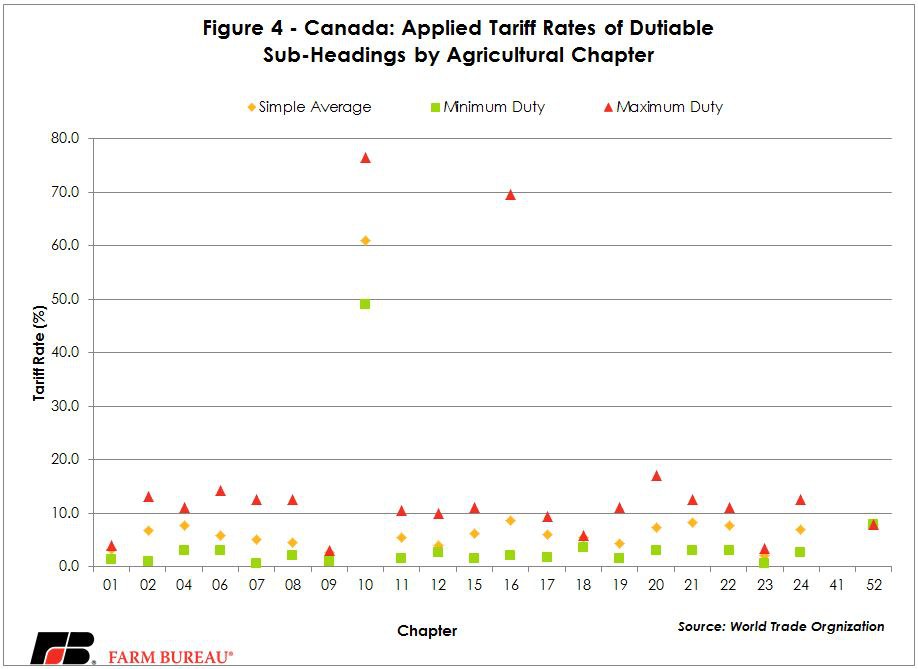

Figure 4 reveals that the simple average applied tariff on dutiable lines in Canada are significantly lower than in Mexico. For most chapters, the average tariff is below 10 percent and the maximums rarely exceed 20 percent, with chapter 10 (grain) and chapter 16 (preparations of meat) serving as outliers.

It is incredibly important to note here, the topic of tariff rate quotas. Tariff rate quotas are instruments where quantities inside a quota are charged lower import duty rates, than quantities over that quota. Tariffs on amounts above the quota can be high. The applied rates discussed in this article include in-quota rates only. TRQs are tools that countries utilize to manage imports of sensitive products into their markets. Canada utilizes TRQs to protect its dairy and poultry industries. If the U.S. were to leave NAFTA, the U.S. would forfeit TRQs that were created through the agreement and would only be able to utilize the TRQs established through the WTO.

All of the applied tariff rates cited in this article are publically available through the WTO. We encourage interested exporters to utilize this resource to better understand the tariff rates your products would face in Mexico and Canada in the absence of NAFTA.

Trending Topics

VIEW ALL