Revisiting Disaster Programs in the Farm Bill

TOPICS

USDA

photo credit: Texas Farm Bureau

Daniel Munch

Economist

Going back almost 100 years, the history of the farm bill largely tracks the history of food production in the United States as the legislation evolves to meet the needs of its modern-day constituents – farmers and consumers. Agriculture’s role in providing food security, and in turn national security, to the United States is more important than ever. And now, work on the next farm bill has started during a period of volatility on every front – political, economic, weather and beyond.

In 2021 alone, farmers and ranchers faced over $12.5 billion in crop and rangeland losses associated with events including extreme drought, wildfires, hurricanes, derechos, freezes and flooding. Of that figure, over $6.5 billion in losses were not covered by existing Risk Management Agency (RMA) programs. To help address these losses and others, the farm bill generally authorizes a range of disaster assistance programs to help producers recover from natural disasters. Understanding these existing programs and the ad hoc disaster assistance that has supplemented farm bill programs will provide clarity as 2023 farm bill discussions ramp up.

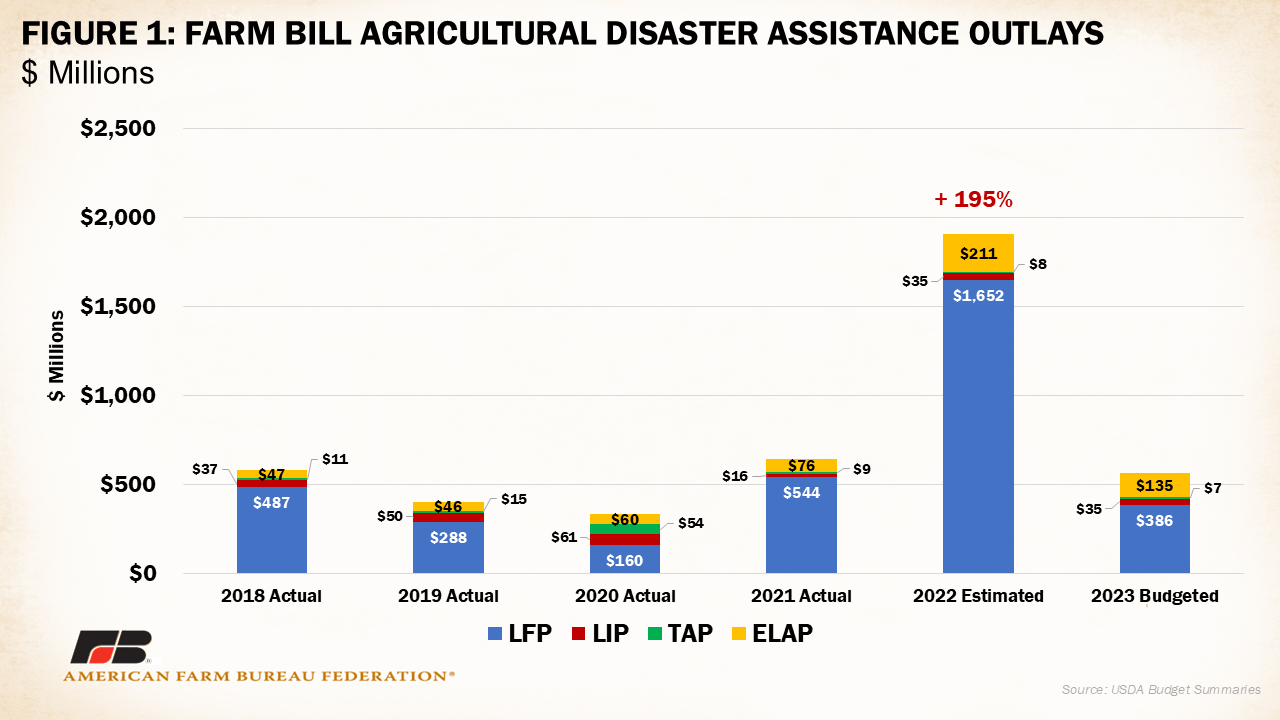

The 2014 farm bill permanently authorized four agricultural disaster programs for livestock and trees: the Livestock Indemnity Program (LIP); the Livestock Forage Disaster Program (LFP), the Emergency Assistance for Livestock, Honey Bees, and Farm-Raised Fish Program (ELAP) and the Tree Assistance Program (TAP). Producers do not pay a fee to participate in these programs and advanced sign-up is not required. They are all administered through the Farm Service Agency (FSA) and funded via the Commodity Credit Corporation (CCC). In fiscal year 2021, $544 million was paid through LFP, $76 million was paid through ELAP, $16 million was paid through LIP and $9 million was paid to producers through TAP. Program expenditures in fiscal year 2022 are expected to increase by 195% across the four programs, with LFP estimated to pay $1.65 billion, ELAP estimated to pay $211 million, LIP estimated to pay $35 million and TAP estimated to pay $8 million. Payments cannot exceed $125,000 per year through LFP. There are no limits on payments for LIP, ELAP or TAP, though to be eligible a producer’s average adjusted gross income over three recent taxable years cannot exceed $900,000.

Livestock Indemnity Program (LIP):

LIP provides payments to eligible livestock owners and contract growers for livestock deaths in excess of normal mortality caused by extreme or abnormal damaging weather, disease, and attacks from wild animals reintroduced or protected by the federal government. The program also compensates producers when an animal is injured as a direct result of an eligible loss condition but is not killed and is sold at a lower price. Covered livestock includes beef and dairy cattle, bison, hogs, sheep, goats, alpacas, deer, elk, llamas, reindeer, caribou, horses, emus, chickens, ducks, geese and turkeys. LIP does not cover wild roaming animals, pets or livestock used for recreational purposes. The payment rate is 75% of the average fair market value of the deceased animal. Rates are reported by the USDA for each type of livestock annually (for example $1,077.94 for adult beef bull, $21.72 for a tom turkey, and $108.52 for a boar 451 pounds or more). A complete list of 2022 payment rates can be found here. For eligible contract growers the payment is based on 75% of the natural average input cost for the applicable livestock. Payments for livestock sold at reduced prices are calculated by multiplying the national payment rate for the livestock category minus the amount the owner received at sale multiplied by the owner’s share.

The 2018 farm bill amended certain parts of the LIP program; these changes went into effect in 2019. They provided eligibility flexibility to unweaned livestock losses from extreme cold regardless of vaccine protocol or management practice. They also expanded coverage for livestock losses due to disease cause or transmission by a vector that is not controlled by vaccination or an acceptable management practice (diseases previously covered under ELAP). The Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018 removed LIP from the $125,000 payment limitation; the limitation now only applies to LFP.

Livestock Forage Disaster Program (LFP):

LFP makes payments to eligible producers who have experienced grazing losses on drought-affected pastureland or on rangeland managed by a federal agency due to a qualifying fire. Producers must own, cash or share lease, or be a contract grower of covered livestock (beef and dairy cattle, bison, deer, elk, emus, horses, goats, llamas, reindeer, and sheep) during the 60 days prior to the beginning date of a qualifying drought or fire. They must also provide pastureland for livestock that is physically located in a county affected by a qualifying drought during the normal grazing period for the county or is managed by a federal agency where grazing is not permitted due to fire. For drought, payments are 60% of the estimated monthly feed cost. For producers who sold livestock because of drought the payment is equal to 80% of the estimated monthly feed cost. Payment frequencies are dependent on drought intensity levels published weekly for a specific county by the U.S. Drought Monitor. Categories are displayed in Table 1. No changes were made to LFP in the 2018 farm bill.

Emergency Assistance for Livestock, Honey Bees, and Farm-Raised Fish Program (ELAP)

ELAP provides payments to producers of livestock, honeybees and farm-raised fish and compensation for losses due to disease, adverse weather, feed or water shortages, or other conditions (such as wildfires) that are not covered under LIP or LFP. Since honeybees and fish are not covered by LIP or LFP, ELAP provides assistance for losses in colonies and fish in excess of normal mortality due to eligible adverse weather or conditions such as colony collapse disorder. For livestock losses ELAP covers livestock feed and grazing losses not due to drought or wildfires on federally managed land and losses resulting from the additional cost of transporting water to livestock due to an eligible drought.

The 2018 farm bill expanded ELAP to assist for costs related to inspection for cattle tick fever regardless of findings. It also provided that payments made to veteran farmers and ranchers will be based on a national payment rate of 90%. As mentioned earlier, livestock losses due to diseases transmitted by vectors that cannot be controlled by vaccines were moved from ELAP to LIP. Lastly, the 2018 farm bill removed the $125,000 payment limitation for ELAP.

In September 2021, USDA updated ELAP to cover feed transportation costs for drought-impacted ranchers. Many ranchers who transported livestock to new feed sources were left out in the original policy, so transporting livestock to feed was added in a later version. The policy allows reimbursements of 60% (90% for socially disadvantaged, beginning, or veteran farmers or ranchers) of feed transportation costs above what would have been incurred in a normal year. This rate is then multiplied by the national average price per mile to transport a truckload of eligible livestock or livestock feed, multiplied by the actual number of additional miles the feed or livestock was transported by the producer in excess of 25 miles per truckload of livestock or livestock feed and for no more than 1,000 miles per truckload of livestock or feed during the program year. The restriction on providing assistance for transportation of water to animals on Conservation Reserve Program land was removed. It also amended “eligible drought” to cover situations in which any area of a county has been rated by the drought monitor as D2 (severe drought) or worse for at least eight consecutive weeks.

Tree Assistance Program (TAP):

TAP makes payments to qualifying orchardists and nursery tree growers to replant or rehabilitate trees, bushes, and vines damaged by natural disasters. Losses in crop production are generally covered by crop insurance or the Noninsured Crop Disaster Assistance Program (NAP). Nursery trees include ornamental, fruit, nut and Christmas trees produced for commercial sale. Trees used for pulp or timber are ineligible. Producers must incur a mortality loss in excess of 15% after adjusting for normal mortality or damage. For replacement, replanting and rehabilitation of trees, bushes or vines the payment calculation is the lesser of (a) 65% of the actual cost of replanting (in excess of 15% mortality) and/or 50% of the actual cost of rehabilitation (in excess of 15% damage), or (b) the maximum eligible amount established for the practice by FSA. Acres planted with program payments cannot exceed 1,000 acres annually.

The 2018 farm bill increased reimbursement amounts for beginning farmers and veteran farmers from 65% to 75% of the cost of replanting in excess of 15% mortality. It also makes the same change for pruning, removal and other costs incurred by salvaging plants. A final rule in April 2022 added the term “commercially viable” as a requisite for eligible tree, bush or vine losses.

Ad Hoc Disaster Assistance Programs

Though permanent disaster assistance programs, crop insurance and NAP provide a substantial safety net to livestock and crop producers, the losses that occur outside the scope of an existing policy or coverage level can be detrimental to a farm business, especially those resulting from recent large-scale weather disasters. Congress has responded to these situations by authorizing additional disaster funds via ad hoc disaster programs like the Wildfire and Hurricane Indemnity Program Plus (WHIP+) and, most recently, the Emergency Livestock Relief Program (ELRP) and Emergency Relief Program (ERP).

Wildfire Hurricane Indemnity Program + (WHIP+)

WHIP+ has been discussed extensively in previous Market Intels including: Reviewing WHIP+ and Other Disaster Assistance Programs, 2020 Disaster Estimations Reveal at Least $3.6 Billion in Uncovered Losses, 2020 Disasters Reveal Gaps in Ad Hoc Aid Legislation , Continuing Resolution Extends Disaster Coverage , and Kentucky, Arkansas Tornadoes, Midwest Derecho Renew Calls for Timely Disaster Assistance. WHIP+ has its origins in the 2017 WHIP and was established under the Additional Supplemental Appropriations for Disaster Relief Act of 2019 with $3.005 billion in funds that were used to provide financial assistance for crop losses many farmers and ranchers experienced in 2018 and 2019 because of record precipitation, extreme cold and snowfall, flooding, hurricanes, wildfires and tornadoes. Eligible crops include those covered under federal crop insurance or the Noninsured Crop Disaster Assistance Program. The payment formula for WHIP+ was based on the expected value of the crop and a WHIP+ payment factor and took into consideration the value of the crop harvested and the insurance indemnity.

Emergency Relief Program (ERP)

On May 16, USDA announced that some commodity and specialty crop producers impacted by natural disasters in 2020 and 2021 will soon be eligible to receive emergency relief payments totaling about $6 billion to offset crop yield and value losses through FSA’s new Emergency Relief Program (ERP), previously known as WHIP+. The funding was from $10 billion authorized in a September 2021 continuing resolution that also expanded ad hoc disaster coverage for additional causes of loss including derechos, winter storms, polar vortexes, freeze, smoke exposure and quality losses for crops. ERP was designed to pay producers in two phases. Phase 1 focuses on streamlining payments to producers whose crop insurance and/or Noninsured Crop Disaster Assistance Program (NAP) data are already on file. Phase 2 focuses on filling payment gaps to cover producers who did not participate or receive payments through existing programs or with other special cases. As of the writing of this article, FSA expected most payments to have been made in Phase 1 while details on Phase 2 have still yet to be released, leaving many producers waiting to receive assistance from disasters that occurred nearly three years ago. ERP program specifications and payment examples for Phase 1 can be found in a prior Market Intel: From WHIP+ to ERP: A New Name for 2020-2021 Ad Hoc Disaster Assistance. Losses in 2022 have not yet been addressed by Congress via an ad hoc program.

Emergency Livestock Relief Program (ELRP)

The same $10 billion that established funds for ERP also supported a livestock-focused ad hoc disaster assistance program called ELRP. The Secretary of Agriculture was allotted $750 million to assist producers of livestock for losses incurred during calendar year 2021 due to qualifying droughts or wildfires. The livestock producers who suffered losses due to drought are eligible for assistance if any area within the county in which the loss occurred was rated by the U.S. Drought Monitor as having a D2 (severe drought) for eight consecutive weeks or a D3 (extreme drought) or higher level of drought intensity during the applicable year. Like ERP, ELRP operates in two phases, also with Phase 2 details not currently available. ELRP assists eligible livestock producers who faced increased supplemental feed costs as a result of forage losses due to a qualifying drought or wildfire in calendar year 2021. For eligible producers, ELRP Phase 1 will pay for a portion of the increased feed costs in 2021 based on the number of animal units, limited by available grazing acreage, in eligible drought counties. Phase I utilizes data from LFP to determine which producers qualify and to calculate payments to assist with supplemental feed costs – with almost identical program requirements to LFP. The payment will be the producer’s gross 2021 LFP payment multiplied by an ELRP percentage (90% for historically underserved producers and 75% for all other producers).

Other Programs

When the President or Secretary of Agriculture declare a county a disaster area or quarantine area, agricultural producers in those or contiguous counties may be eligible for low-interest disaster loans through FSA called Emergency Loans, or EM loans. EM loan funds may be used to help eligible farmers, ranchers and aquaculture producers recover from production losses (when the producer suffers a significant loss of an annual crop) or from physical losses (such as repairing or replacing damaged or destroyed structures or equipment or for the replanting of permanent crops such as orchards). A qualified applicant can then borrow up to 100% of actual production or physical losses (not to exceed a loan total of $500,000). EM loans are permanently authorized by Title III of the Consolidated Farm and Rural Development Act. In fiscal year 2022 the program received $37.7 million of new loan authority.

Several other USDA programs assist producers in repairing, restoring and mitigating disasters on private land including the Emergency Conservation Program (ECP), Emergency Forest Restoration Program (EFRP) and Emergency Watershed Protection Program (EWP). The former two programs are administered by the FSA, which pays participants a percentage of the cost to restore land to a productive state. ECP also funds water for livestock and installing water conserving measures during times of drought. Administered by USDA’s Natural Resources Conservation Service and U.S. Forest Service, EWP assists and sponsors landowners in implementing emergency recovery measures for runoff control and erosion prevention to relieve imminent hazards to life and property created by a natural disaster.

The Dairy Indemnity Payment Program (DIPP) allows the Secretary of Agriculture to indemnify affected dairy farmers and manufacturers of dairy products who, through no fault of their own, suffer income losses with respect to milk or milk products containing harmful pesticide residues, chemicals, or toxic substances, or that were contaminated by nuclear radiation or fallout. The program is further described in a dairy programs-focused Market Intel here.

Conclusion

The 2018 farm bill reauthorized many programs that provide producers a safety net against unexpected crop and livestock losses associated with natural disasters. Additional congressional authorizations through ad hoc programs like WHIP+ and ELRP/ERP intend to fill the gaps in crop insurance and existing disaster assistance programs. While ad hoc assistance is a welcome addition in supporting farmers and ranchers, continued improvements to existing programs and crop insurance offerings can help fill gaps that leave some producers vulnerable. As discussions ramp up for the 2023 farm bill, understanding the history of existing disaster assistance programs and how they’ve performed under unprecedented volatility will allow for more informed recommendations.

Much of the above information is based on summaries provided by the Congressional Research Service and in the Federal Register.

Fact Sheets:

Trending Topics

VIEW ALL