Reviewing U.S. Dairy Supply Management Efforts

TOPICS

Supply Management

photo credit: Getty

John Newton, Ph.D.

Former AFBF Economist

Following five consecutive years of low milk prices and record U.S. milk production, some U.S. dairy farmers are again interested in coordinated intervention in dairy markets -- specifically, a milk supply management program designed to increase the price farmers receive for their milk.

Farm Bureau grassroots leaders debated this issue in 2019 and ultimately decided to oppose a mandatory quota system with the willingness to consider a flexible supply management system that is administered through the marketplace and not through the federal government, i.e., milk processors and cooperatives alongside individual dairy farmers.

Milk supply management programs, which provide incentives or penalties to limit perceived over-production, have been used previously in the U.S. with mixed results. These programs included a USDA-administered milk diversion program, government-administered and industry-funded herd buyout programs, and base-excess plans, i.e., two-tiered pricing. In addition, a milk supply management program was heavily debated during the 2014 farm bill. Today’s Market Intel article reviews these previous attempts to manage the U.S. milk supply.

USDA-Administered Milk Diversion Program

According to the Government Accountability Office, USDA’s purchases of surplus dairy products through the dairy price support program increased from $247 million in 1979 to $2.7 billion in 1983. The milk diversion program was a temporary program enacted by Congress in 1983 to address excessive dairy product purchases and the costs associated with maintaining the dairy price support program.

Under the milk diversion program, which was funded through a farmer assessment of 50 cents per hundredweight, farmers were paid to reduce their milk marketings by 5 percent to as much as 30 percent. For every hundredweight of milk production not produced relative to their established base level of production, dairy farmers were paid $10.

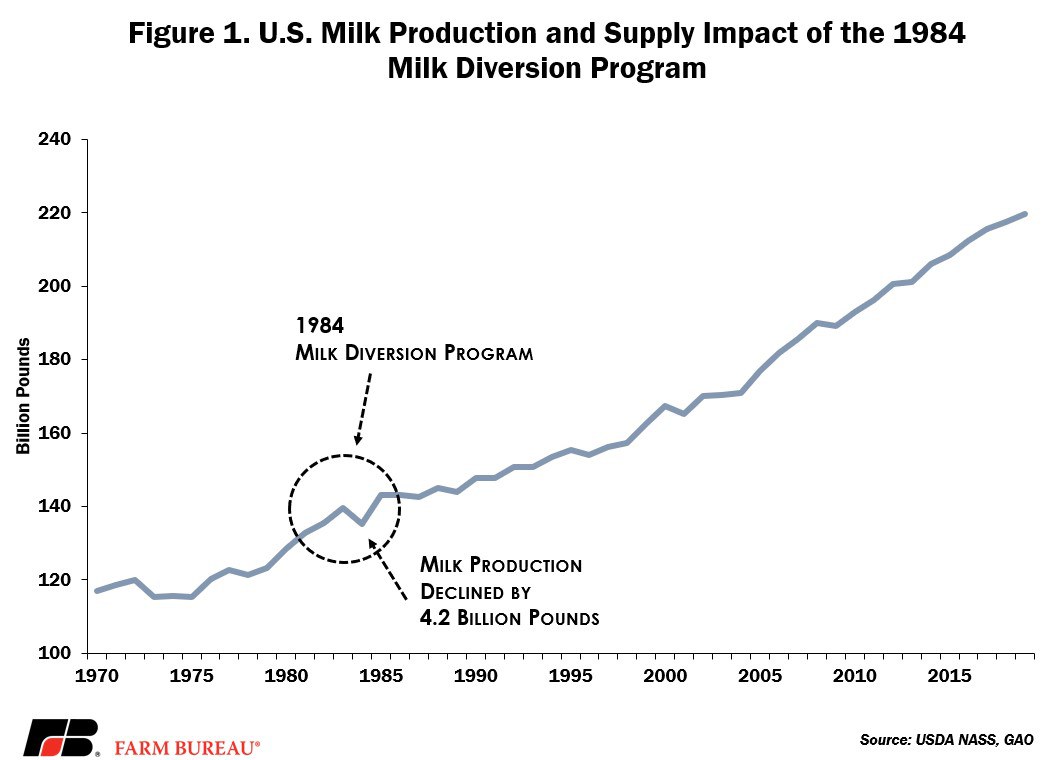

The milk diversion program was in effect from January 1984 to March 1985. Approximately 38,000 commercial dairy operations in the U.S. participated in the milk diversion program. Total milk diversion payments were $955 million, and GAO estimated that milk production was reduced by 3.74 billion to 4.11 billion pounds in 1984. Figure 1 highlights U.S. milk production and the supply response to the 1984 Milk Diversion Program.

While the milk diversion program had the desired effect of reducing milk production, GAO survey results revealed that the program’s likely participants had already reduced milk production below their base levels. Nonparticipants were those dairy farmers who were actively expanding sales. These adverse selection and moral hazard issues plagued the program, and ultimately, the milk diversion program had no measurable impact on the national average milk price or the trend in milk production.

Following the milk diversion program, U.S. milk production quickly recovered in 1985, increasing by 7 billion pounds to a record 143 billion pounds. The lack of success in the milk diversion program and the quick recovery in the U.S. milk supply ultimately led to more government intervention efforts.

Milk Termination and Herd Buyout Programs

Milk termination and herd buyout programs were designed to reduce the milk supply by removing dairy cows from production. The first effort occurred in the 1985 farm bill with the Milk Production Termination Program. According to GAO, the goal of the program was to reduce milk production by 12 billion pounds, or nearly 9 percent from the base period of 1985.

The termination program was effective for an 18-month period beginning in April 1986 and provided payment to dairy farmers who entered into a contract with USDA to terminate milk production, e.g., cull or export dairy cows. Assessments on dairy farmers helped offset the costs of administering and funding the termination program. The program was limited in that no more than 7 percent of the dairy herd could be removed each calendar year.

Participating dairy farmers were prohibited from entering dairying for at least five years. As shown in Figure 1, while the growth in milk production remained flat through 1987, national milk production did not decline as non-participating operations expanded production during the 18 months of the termination program.

Similar to the milk diversion program, the milk termination program was also subject to a free-rider and adverse selection problem whereby any production declines attributable to a decline in the milking herd from the termination program was offset by non-participating operations expanding output. The inability to measurably reduce milk production was counter to the primary goal of the program to reduce the U.S. milk supply by 9 percent.

Following the USDA-administered termination program, dairy farmer cooperatives collectively formed an industry-funded and voluntary herd buyout program. This herd buyout program paid dairy farmers to reduce milk output or take whole dairy herds out of production.

Over a 12-month period, the goal of the herd buyout program was to collectively reduce the nation’s milk supply by slightly more than 1 billion pounds. During 2004, the herd buyout program contributed to a decrease in the dairy herd size by 150,000 head. In 2009, the program contributed to a 250,000-head reduction. Over the 7-year life of the program, the herd buyout program is estimated to have removed 510,000 milking cows from production. Figure 2 details the year-over-year change in the number of dairy cattle.

Dairy Market Stabilization Program

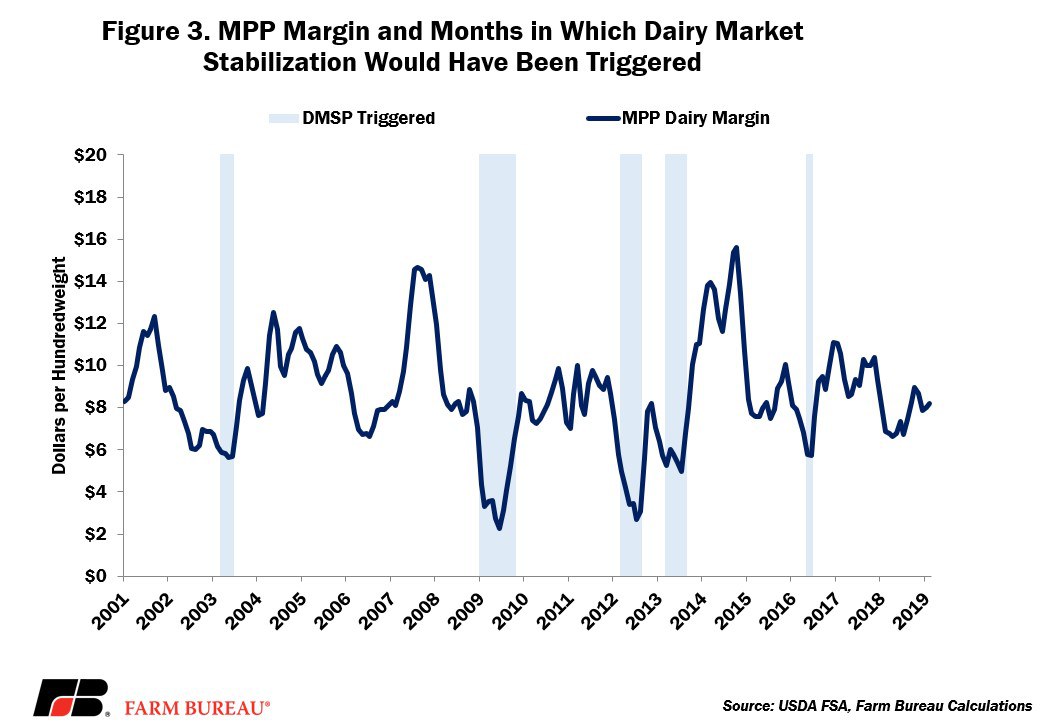

The next effort to control the milk supply occurred during the 2014 farm bill debate. The Senate version of the 2014 farm bill coupled the Margin Protection Program, a commodity support program for dairy producers, with the Dairy Market Stabilization Program. DMSP was a supply management program designed to enhance milk prices by levying a financial penalty on dairy farmers who did not reduce their milk supply when MPP margins fell below a specified threshold that triggered program payments. Although participation in the MPP was voluntary, under the Senate proposal, those enrolled in the MPP would have been required to participate in the DMSP.

DMSP would have been triggered when the MPP margin fell below $6.00 per cwt for two consecutive months, or below $4.00 per cwt for a single month. Farmers delivering a milk volume above the DMSP-assigned base would see their milk check reduced by as much as 8 percent. Farmers producing below their production base would not have been subject to a financial penalty.

In reviewing historical MPP margins, the DMSP program would have been triggered during 2003, 2009, 2012 and 2013. Had DMSP been included in the final 2014 farm bill, it would have been triggered only once in 2016, when MPP margins dipped to below $6.00 per hundredweight for two consecutive months, Figure 3. Thus, despite the financial struggles in the dairy industry in the last five years, in only one two-month period would the DMSP have been activated in an attempt to stabilize milk prices and margins.

Base-Excess Plans

The milk diversion and herd buyout programs were USDA-administered or quasi-voluntary efforts. The programs in place today are cooperative-led base-excess programs. (At one point in time, from 1965 to 1981, base-excess style programs were authorized and federally-administered under the Agricultural Marketing Agreement Act.) These two- or multi-tiered milk pricing programs are designed to provide dairy farmers with an economic incentive to adjust milk production to match seasonal demand for milk and dairy products.

Under a base-excess plan, producers establish a base level, or quota level, of milk production needed to service the market. For any excess milk deliveries beyond the base level, i.e., over-produced milk, dairy farmers receive a discounted or penalized price that is lower than the prevailing market price.

These base-excess plans match a milk processor’s milk supply with the processing and marketing capacity and provide an opportunity for dairy plants and cooperatives to effectively market only the volume of milk and dairy products demanded by their customers.

Figure 4 highlights the economic impact of a base-excess program on the weighted average milk price ultimately received by a dairy farmer producing within the base (quota) level and more than the base level (assuming a base milk price of $20 per hundredweight and an over-base value of $15 per hundredweight).

As identified in Figure 4, under a base-excess plan there are economic penalties associated with producing milk in excess of the base allotment. However, under this simple example of a base-excess plan, if the over-base price of milk, i.e., the marginal revenue, exceeds the marginal cost of production, there will be no economic incentive to reduce milk production. As a result, the costs of balancing the milk supply in a base-excess program will be borne by the producers with the highest costs.

Summary

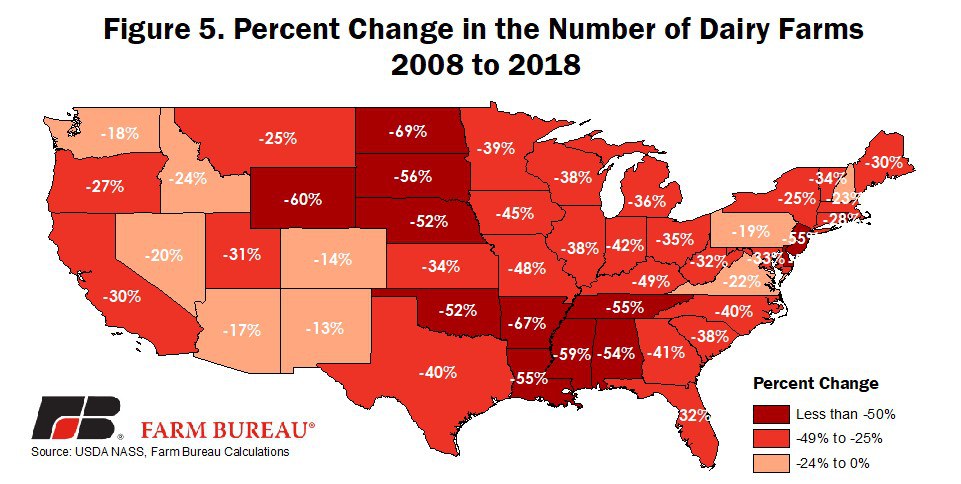

Historically, periods of low milk prices were temporary. Herd culling and the loss of farm operations resulted in milk supply adjustments that, when combined with the demand for dairy products, helped to return milk prices to higher levels. However, during this most recent downturn in the dairy economy and despite the U.S. losing 7 percent of licensed dairy operations in 2018, and 34 percent over the last decade, Figure 5, milk production continues to be record high, and only recently have cow numbers started to decline from prior-year levels.

The lack of a production response has contributed to lower milk prices and spiked interest in programs designed to reduce milk output during times of low milk prices or profitability. Today’s article provided an overview of supply management-type programs that have been used or proposed in the past.

The performance of these programs has had mixed results. The milk diversion program, the milk termination program and the herd-buyout program all contributed to fewer milking cows, but without industry-wide participation suffered from free-rider, adverse selection and moral hazard problems. Over-base programs are likely successful at balancing regional supply and demand constraints, but without region-wide or national participation, over-base programs are unlikely to have the desired effect of lifting average milk prices in the current end-product pricing scheme.

Farm Bureau members have debated milk supply management many times throughout the years. In 2019, our members voted to oppose a mandatory supply management program but were supportive of considering a flexible supply management program. Such a program should be administered by the marketplace and would include coordination among milk processors, cooperatives and dairy farmers to ultimately balance supply and demand. Importantly, such a program can operate within the confines of a free market economy without government intervention.

While this type of coordination could prove beneficial in the short-run, some reflection should be given on the long-run, such as considering reforms that would drive further investment and innovation in the U.S. dairy sector as well as expand our market access around the world. As a first step Farm Bureau dairy farmer leaders will convene in 2019 and consider these very issues as they relate to milk pricing reform and, ultimately, the profitability and viability of U.S. dairy farmers.

Trending Topics

VIEW ALL