Record High Cheese Stocks Weigh on Milk Prices, But Should They?

photo credit: Getty

John Newton, Ph.D.

Former AFBF Economist

In the late 1980s USDA effectively cleared the shelves of excess dairy products. Over a five-year period, as part of the now-expired dairy price support program, USDA purchased 1.5 billion pounds of butter, 1.7 billion pounds of cheese, and 2.7 billion pounds of non-fat dry milk totaling $6.3 billion dollars (Government Accountability Office). The dairy price support program remained in effect through the 2014 Farm Bill but saw limited use following 2009 due to milk prices above support levels.

Cheese Stocks are Record-High

Now in 2017, with U.S. milk production expected to climb to a record 217.3 billion pounds, commercial dairy product inventories have reached highs not seen since the days of the price support program.

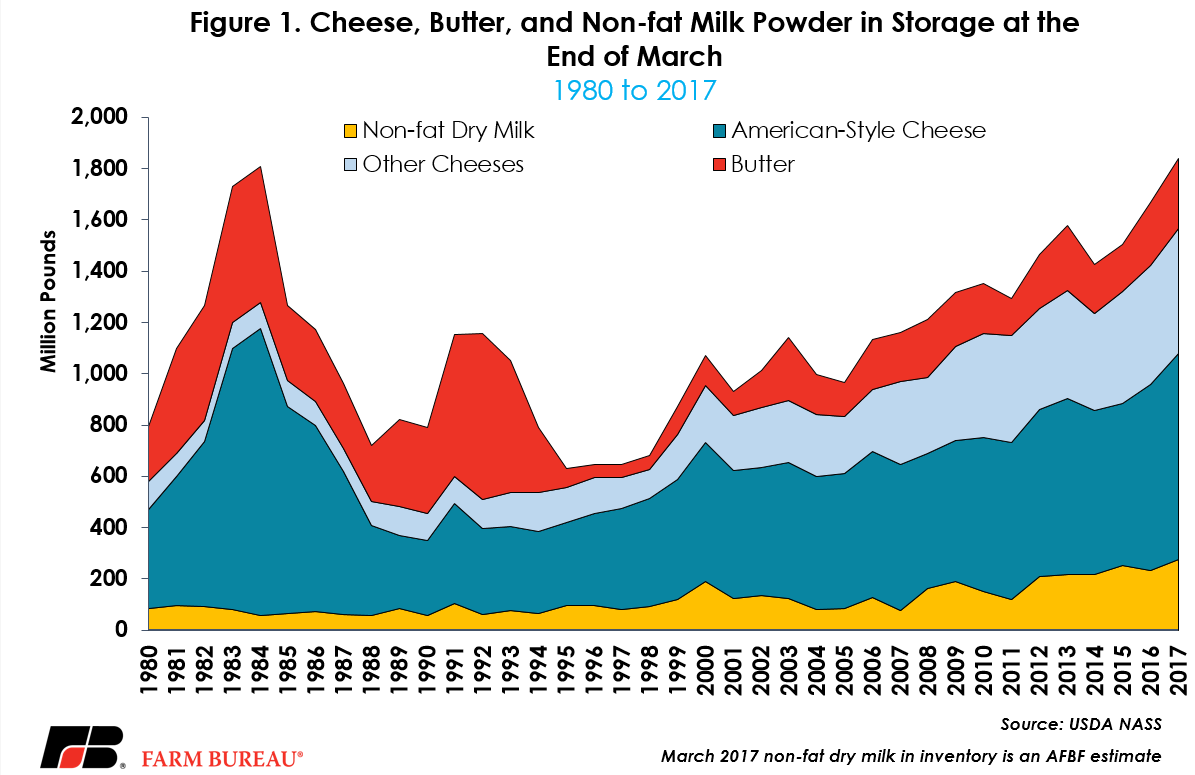

USDA’s April 24, 2017, Cold Storage report revealed March 2017 inventory levels for total cheese at a record high of 1.3 billion pounds. American-style cheese in cold storage was 803 million pounds and butter storage was 273 million pounds. For American-style cheese and butter, these March inventory levels are the highest levels since 1984 and 1993, respectively.

Additionally, USDA’s April Dairy Products report revealed manufacturers’ stocks of non-fat dry milk at 260 million pounds, 10 million pounds shy of the record-high set in 2015. USDA’s May Dairy Products report could show a new record-high inventory level for non-fat dry milk. For the week ending April 28, 2017, nearby Class III milk futures traded as much as 38 cents lower following the Cold Storage report.

Demand Also Record-High

These higher dairy product inventories are to be expected for a variety of reasons. First, the U.S. is expected to produce 70 billion more pounds of milk in 2017 than it did in 1990. These additional pounds of milk are turned into a variety of perishable and non-perishable dairy products, including beverage milk, cheese, butter, yogurt, and ice cream. While fluid milk has a limited shelf-life, non-perishable dairy products can be stored (albeit not indefinitely) and sold later based on market conditions. Milk prices have declined substantially in recent years, and at current low prices, there may be an incentive to store dairy commodities in case prices rally in the months ahead.

Second, U.S. consumers are shifting their preferences for how dairy products are consumed. In 2015, USDA’s Economic Research Service reported per capita consumption of fluid milk at 155 pounds per person, down 24 percent over the last two decades. Due to the decline in fluid milk consumption, the share of the U.S. milk supply used to produce beverage products has declined from over 60 percent in the 1960s to approximately 33 percent in 2015 (USDA Dairy Programs).

Consumers are shifting their dairy product consumption out of beverage products and into yogurts, butter, and cheeses (completely baffling the author, per capita consumption of ice cream is down 14 percent). Compared to 20 years ago on a per capita basis, U.S. consumers are eating 139 percent more yogurt, 22 percent more butter, 20 percent more American-style cheese, and 40 percent more other cheeses (Italian-style). To meet this additional demand for dairy products more products need to be held in the supply chain.

Third, it’s not only the U.S. consumer who is demanding more U.S.-produced dairy products. Since 2000, the U.S. dairy industry has grown exports from less than 5 percent of the U.S. milk supply to nearly 15 percent of the U.S. milk supply. One day’s worth of milk production out of every week is needed to fulfill the overseas demand for U.S.-produced dairy products. Exports of non-fat dry milk powders now exceed one billion pounds each year compared to less than 50 million pounds exported in 2000. Similarly, the U.S. exports more than 500 million pounds of cheese each year, representing 5 percent of cheese production. This is up from only 1 percent of cheese production exported in 2000.

Combining the growing export market, changing preferences of the U.S. consumer, and a larger U.S. population, consumption of dairy products is higher than ever before. In 2015, consumption of butter averaged 5.3 million pounds per day, 2.1 million pounds per day higher than in 1995. Italian-style cheese consumption in 2015 averaged 21 million pounds per day and is up more than 10 million pounds per day from 1995 consumption levels. Similar patterns are observed for American-style cheese (+4.4 million pounds per day) and non-fat dry milk powders (+3.7 million pounds per day).

With higher levels of consumption, higher inventory levels are needed in the supply chain to prevent disruptions in product availability. An adequate inventory level ensures that domestic and foreign customer orders can be met in a timely manner even in face of disruptions along the supply chain, e.g. plant shutdown, reduced milk supply or interruptions in transportation.

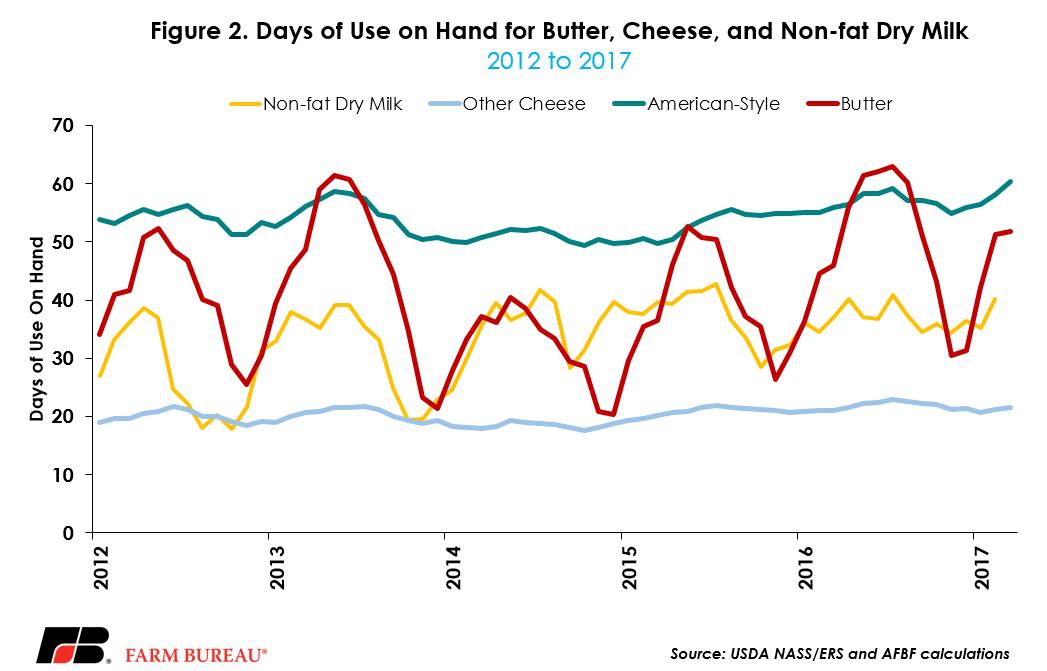

Consider that while current cheese stocks are record-high, the inventory of American-style cheese represents 60 days’ worth of consumption and is only marginally higher than levels experienced in 2016, Figure 2. Italian-style cheeses have less than one month of consumption on hand. Days of butter and non-fat dry milk on hand are higher than prior year levels, but as evidenced in Figure 2 these inventories are expected to be drawn down following the spring flush.

Summary

While dairy product inventories are record-high, the U.S. is also consuming and exporting more dairy products than ever before. Evaluating stock levels in the context of only the supply side of the balance sheet misses the interrelationship between supply and demand. Thus, by evaluating dairy product inventories in the context of higher consumption, it's revealed that inventories may not be as burdensome as recent milk price changes may suggest.

Since 2014 a variety of factors have combined to roil dairy markets, and during this time milk prices have fallen by nearly 40 percent. However, these lower milk prices, especially relative to Oceania and EU-28 prices, are creating opportunities to increase consumption of U.S.-produced dairy products even more. USDA’s Foreign Agricultural Service reported that February 2017 dairy product exports were at the highest levels observed since May 2015. Higher exports bode well for pulling down domestic stocks and potentially raising milk prices – as was the case in 2014.

Trending Topics

VIEW ALL