Previewing 2019 Agricultural Emissions

TOPICS

Greenhouse Gas

photo credit: AFBF Photo, Morgan Walker

John Newton, Ph.D.

Former AFBF Economist

The Environmental Protection Agency provides annual estimates of man-made greenhouse gas emissions in the U.S. by emissions source, as well as estimates of the amount of carbon trapped in forest and vegetation soil. Previous articles reviewed the emissions for both 2017 (Agriculture and Greenhouse Gas Emissions) and 2018 (Agriculture’s Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Sinks), as well as trends in carbon sequestration (Reviewing U.S. Carbon Sequestration).

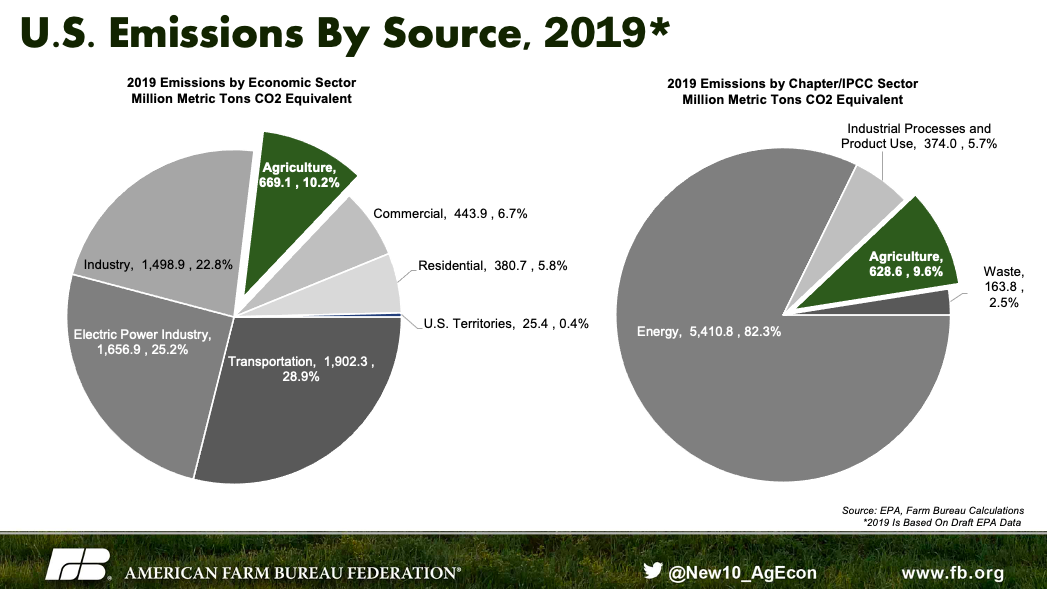

These reports not only highlight U.S. agriculture’s minimal contribution to total U.S. emissions – 10% – they emphasize how productivity gains in crop and livestock production help agriculture reduce per-unit emissions. An equally key takeaway is the impact increased investment in agricultural research can have in helping farmers and ranchers play a direct role in capturing more carbon in the soils with voluntary and incentive-based practices and markets.

Today's article provides an overview of 2019 emission estimates in EPA’s most recent Draft Inventory of U.S. Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Sinks: 1990-2019 report. This Draft Greenhouse Gas Emissions Inventory is available for public comment through March 15. The final report is expected to be published by April 15.

2019 Emissions and Sinks

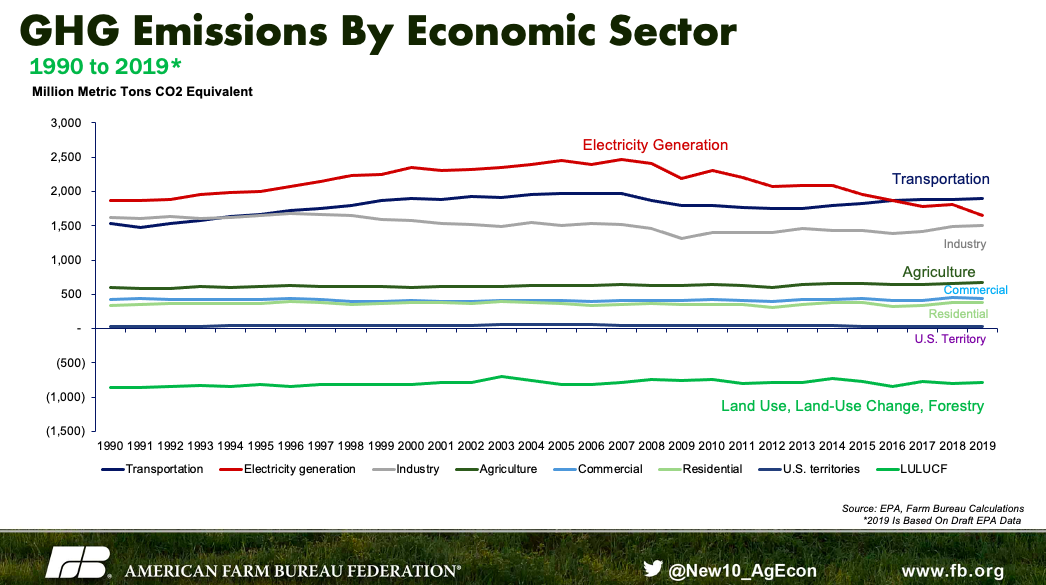

During 2019, total U.S. emissions from all man-made sources totaled 6.6 billion metric tons in CO2 equivalents. Emissions in 2019 were down 1.7%, or 166 million metric tons, from 2018. Land use, land-use changes and forestry trapped 789 million metric tons of carbon in the soils, representing 12% of total U.S. emissions. Combined, the net greenhouse gas emissions in 2019 totaled 5.8 billion metric tons, down 1.8% from 2018. These estimates put both emissions and net emissions at the third-lowest level in the last 25 years.

The largest emissions source was the transportation sector, representing 28% of total emissions and totaling 1.9 billion metric tons. Transportation emissions were up 1%, or 19 million metric tons, from the prior year. Following transportation, electricity generation represented more than 25% of total emissions at 1.7 billion metric tons. Emissions from the electric power industry were down 8% from 2018 and were at the lowest level since the series was first recorded in 1990. The industrial sector, e.g., iron and steel production or cement production, represented nearly 23% of all emissions at 1.5 billion metric tons. Emissions from the industrial sector were up nearly 1% from 2018. The commercial and residential sectors and U.S. territories represented approximately 13% of U.S. emissions and were down 0.2% from 2018.

Agricultural Emissions in 2019

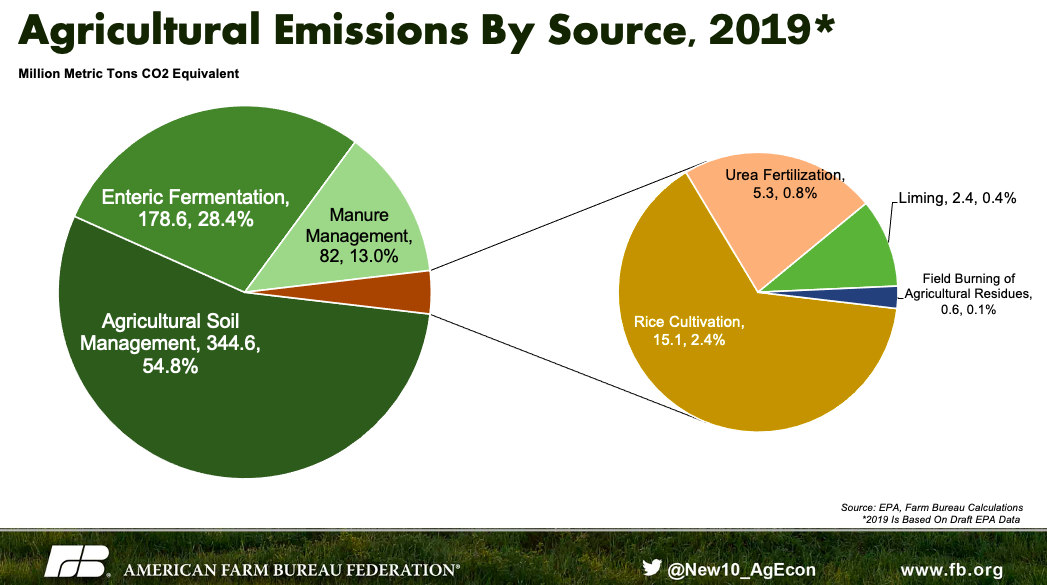

Emissions from agriculture totaled 669 million metric tons in CO2 equivalents during 2019, up 1.1%, or 7.5 million metric tons, from the previous year. Based on methodology consistent with the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, U.S. agricultural emissions totaled 629 million metric tons, up 1.2% from 2018. The largest source of U.S. agricultural emissions was agricultural soil management, e.g., fertilizer applications or tillage practices, at 345 million metric tons, approximately 55% of all agricultural emissions and only 5% of total U.S. emissions.

Following agricultural soil management, livestock-related emissions from enteric fermentation and manure management contributed 179 million metric tons and 82 million metric tons, respectively, to total U.S. emissions. These two emission sources represented 41% of agricultural emissions, but only 4% of total U.S. emissions. Other agricultural emissions sources include rice cultivation at 15 million metric tons, urea fertilization at 5.3 million metric tons, liming at 2.4 million metric tons and field burning at 0.6 million metric tons. Combined, these categories represented less than 4% of agricultural emissions and 0.4% of U.S. emissions. As a percent of total U.S. emissions, and depending on the estimation methodology, U.S. agriculture represents approximately 10% of total U.S. emissions.

Agricultural Productivity and Emission Trends

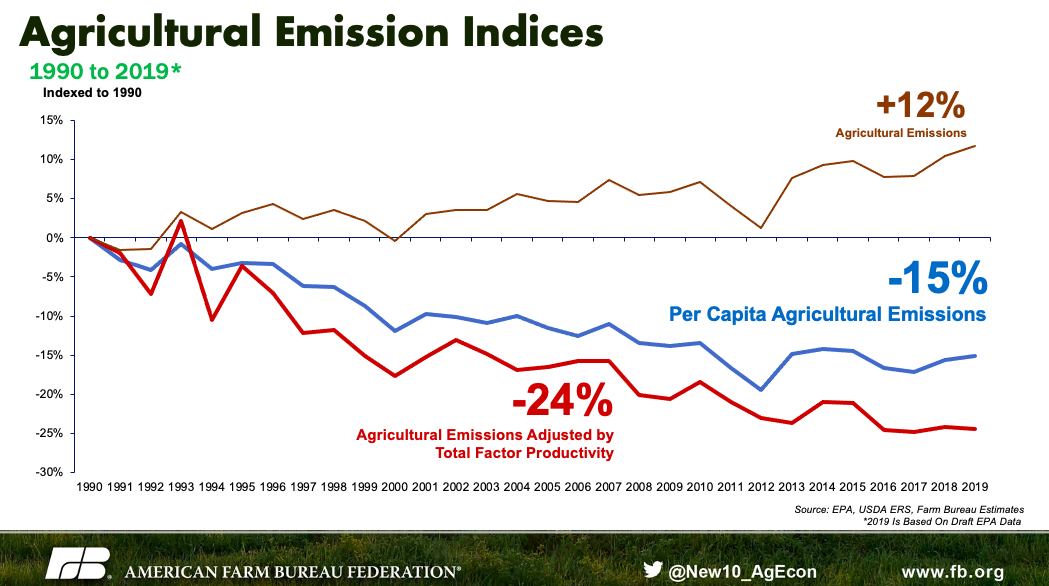

Since 1990, U.S. agricultural emissions have increased by 12%. However, when considering agricultural emissions, productivity gains provide an important perspective. For example, through improvements in crop yields, animal nutrition and breeding, compared to 1990, the U.S. is producing 80% more pork (12-billion-pound increase), 79% more corn (6-billion-bushel increase), 51% more milk (75-billion-pound increase) and 20% more beef (4.5 -billion-pound increase).

USDA’s Economic Research Service estimates indices of farm output, input and total factor productivity (Agricultural Productivity in the U.S.). Compared to 1990, the U.S. is producing 43% more food and agricultural products, while largely using the same amount of inputs, like fertilizer. During the same time, we’ve lost more than 30 million acres of cropland in the U.S. Moreover, when you consider that the U.S. population has increased by 31%, or 79 million people, U.S. agriculture has more mouths to feed than ever before. Put simply, U.S. farmers and ranchers are producing more food, fibers and renewable fuels for more people while using less land and conserving more natural resources.

When taking these productivity trends into consideration, we flip the 12% increase in total U.S. agricultural emissions since 1990 on its head. Per capita agricultural emissions have declined by 15% since 1990, and when agricultural emissions are adjusted by productivity gains, it’s estimated that aggregate agricultural per-unit emissions have declined by more than 20%.

Summary

During 2019, U.S. emissions from all man-made sources totaled 6.6 billion metric tons in CO2 equivalents, down 1.7% from 2018. When taking into consideration carbon trapped in the soils through forestry, grasslands, wetlands and cropland, U.S. greenhouse gas emissions were reduced by 12% to a net emissions level of 5.8 billion metric tons, down 1.8% from 2018.

Emissions related to agriculture totaled 669 million metric tons during 2019, up 1.1% from the previous year. Based on IPCC methodology, U.S. agricultural emissions totaled 629 million metric tons in 2019, also up slightly from the prior year. As a percentage of total U.S. emissions, U.S. agriculture represents approximately 10% of emissions, with livestock-related emissions at only 4%.

When factoring in productivity and population gains, however, both per-unit and per capita agricultural emissions are declining. That means U.S. agriculture is producing more food, fibers and renewable fuels for more people while using fewer resources and emitting less carbon.

The story does not end with productivity gains. Increased investment in agricultural research can help develop new cutting-edge plant and animal technologies to capture more carbon in the soil and reduce livestock-related emissions. Voluntary and incentive-based tools will complement these research efforts to ensure that while farmers and ranchers help to achieve climate goals, they also remain economically sustainable.

Beginning next week, AFBF Market Intel is launching a five-part series highlighting agricultural ecosystem credit markets and the opportunities and challenges they present to farmers.

Trending Topics

VIEW ALL