NAFTA: Where 's the Beef?

AFBF Staff

photo credit: AFBF Photo, Dylan Davidson

Cattle trade flows play an important role across the U.S. well beyond trade deficits and surpluses, or volumes. They provide numbers to keep feedlots full and packing plants running efficiently. They provide flexibility to adjust to market conditions along the supply chain in all three countries. In turn, these cattle become beef, and free trade agreements allow for our processing sector to ship different cuts to those countries that desire them the most. The U.S. would be hard pressed to consume domestically the variety meats from its own cattle supply; these by-products would otherwise be considered waste without access to other markets that preferred these meats. Ultimately, these relationships have increased the value of the carcass in the U.S., finding consumers that value each of these cuts. This week’s NAFTA article takes a deep dive into the details of cattle and beef trade between the U.S., Canada, and Mexico.

North American Cattle Flow

The North American Free Trade Agreement has mutually benefitted the Mexico, Canada and U.S cattle industries by allowing competitive advantage and economics to drive trade flows among the three countries. The U.S. cattle herd totaled 94 million head at the beginning of 2017, compared to Canada’s 12 million and Mexico’s 17 million. Extracting the dairy cows from this number yields beef herds approximating 80 million, 10 million and 7 million for the U.S., Canada and Mexico, respectively. The sheer size of the U.S. cattle industry gives it significant advantages in economies of scale and infrastructure. Another large difference is that cattle are raised in all 50 states in the U.S., with regional differences in production systems and local challenges. In Canada, Alberta leads the nation in beef production, home to almost 60 percent of feeder cattle. Comparatively, Texas has the largest beef cattle inventory in the U.S., at 12.6 million head, but only represents about 15 percent of the U.S. total.

Live Cattle Trade Matters Regionally

The U.S. trades significantly more live cattle with Mexico than with Canada. However, it is still a relatively small proportion compared to the national herd. Mexico primarily ships feeder animals to the southern plains where they enter into feeding programs dependent on the marketing environment, feed price and grass conditions. This could mean they are placed directly into feedlots or placed on grass. The U.S. primarily ships breeding stock south of the border. To put the volume in perspective, so far this year, beef cattle imports from Mexico have averaged 23 thousand head a week. Total U.S. beef cattle exports to Mexico over the last five years have been under 15 thousand head. Still, the number of Mexican cattle coming across the border is still small relative to the size of the U.S. herd. In 2016, the U.S. imported just under 1 million head from Mexico, representing less than 7 percent of the cattle on feed as of Jan. 1, 2017.

Cattle coming down from Canada, on the other hand, tend to be slaughter-ready, either finished-fed cattle, slaughter cows or slaughter bulls. These three groups account for more than 50 percent of the cattle imports on a weekly basis and can be as high as 98 percent of the cattle imported in a given week. Feeder cattle imports this year have averaged about 3 thousand head a week. U.S. exports of live beef cattle to Canada have historically been rather flexible, ranging from feeders, fed or breeding cattle, depending on marketing and competitiveness factors in cattle feeding and packing sectors.

More than half the packing plants in Canada are in Ontario and Quebec, placing the largest feeding province (Alberta) more than 1 thousand miles from those plants. Alberta is home to five of the larger federally inspected plants, and historically the U.S. has played a role in slaughtering fed cattle raised in Canada.

However, that could be changing. The Canadian cattle herd has shrunk significantly in recent years and is not expected to regain numbers, which could change the live cattle trade flows between the U.S. and Canada. Packing plants in Canada will need both volume and profits to stay in business. A smaller cow herd could lead to closures of slaughter facilities, resulting in more cattle shipped to the U.S. Under another possible scenario, packing capacity in Canada could reach an optimal level, prompting Canada to send fewer slaughter animals to the U.S.

Beef

On the meat side, trading between NAFTA countries is more balanced. The U.S. is a net exporter in beef products, shipping most variety meats and frozen bone-in products overseas. In 2016, Mexico’s beef trade balance with the U.S. was almost even. Mexico tends to buy a lot of variety meats from the U.S. and ships both fresh and frozen muscle cuts to the U.S.

In contrast, Canada in 2016 shipped 173 thousand metric tons more product to the U.S. than the U.S. shipped to Canada. The largest category was boneless processed beef, or hamburger, accounting for 145 thousand metric tons of the trade deficit.

Still, Mexico and Canada consistently rank in the top five export destinations in terms of value for U.S. fresh and chilled beef products and in the top 10 for U.S. frozen products. In terms of volume, Mexico and Canada are a top 10 destination for frozen product and in the top five for fresh and chilled product. The U.S. shipped $1.3 billion of $5.2 billion in fresh and frozen beef products (excluding variety meats) to NAFTA countries in 2016. The U.S. imported $2.1 billion in fresh/frozen beef products from NAFTA countries, more than 40 percent of total fresh and frozen beef products. Imported variety meat values totaled $245 million dollars in 2016, with over 50 percent coming from Mexico and Canada. Exports totaled $756 million, with 23 percent heading to Mexico or Canada. On a dollar basis, the U.S. imported $752 million more in beef products than it exported among NAFTA countries, but U.S. total beef trade is still a net exporter worldwide, generating over $1 billion in trade surplus in variety meats, fresh, frozen and chilled bone-in and boneless beef.

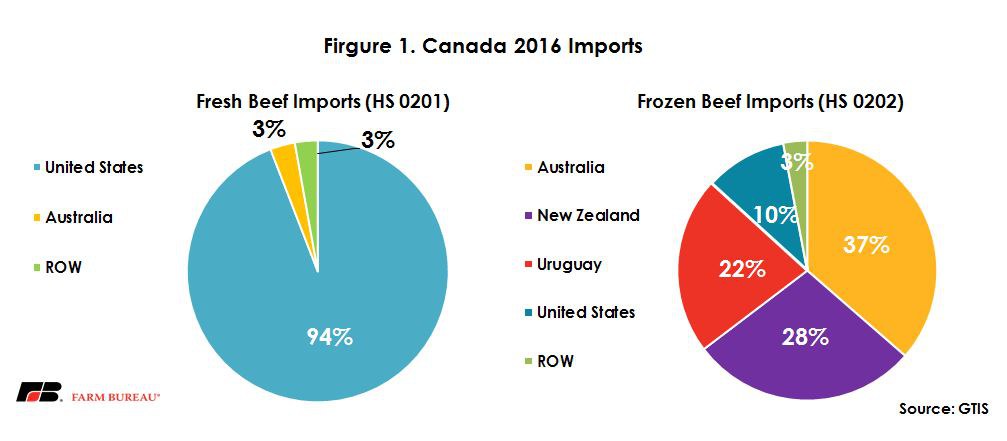

The United States is by far the dominant supplier of fresh beef to Canada. In 2016, the U.S. had a 94 percent market share by volume of the imported fresh beef market. The U.S. has a smaller share of the imported frozen beef market, with 10 percent market share by volume. By value, Canada is the world’s 11th largest fresh beef importer and the 12th largest frozen beef market.

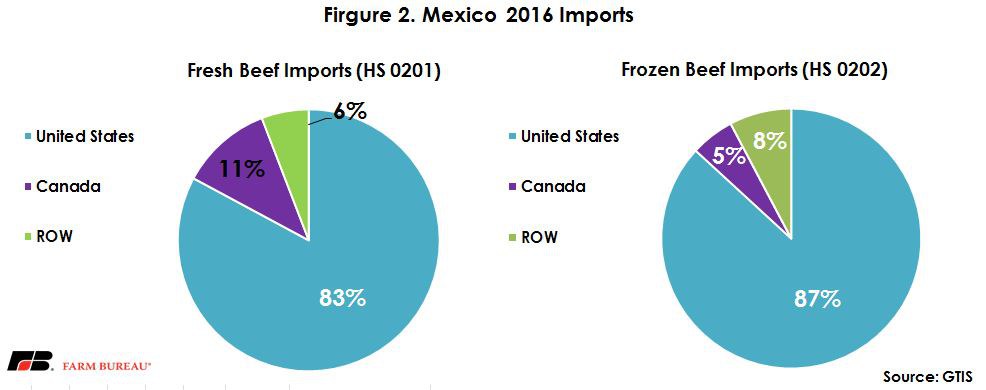

The United States is by far the dominant supplier of beef to Mexico. In 2016, the U.S. had an 83 percent market share by volume of the imported fresh beef market. The U.S. had an 87 percent market share by volume of the imported frozen beef market. By value, Mexico is the world’s ninth largest fresh beef importer and the 30th largest frozen beef market.

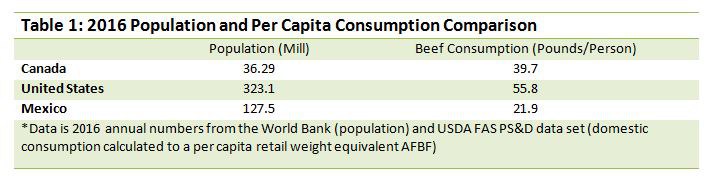

It’s important to note two details. It’s not just the size of the cattle herds between the countries but also the population and the amount of beef consumed that affect these trade flows. The U.S. population is more than double the size of Mexico’s and almost 10 times the size of Canada’s. Table 3 shows populations estimated in 2016 from the World Bank and estimated beef consumption from USDA Foreign Agricultural Service Production, Supply and Disposition database. Canadians consume beef in largely the same way U.S. consumers do with a heavy focus on higher-end meat products. Mexico in contrast consumes less beef overall and consumes more variety meats. Some of this difference can be explained by income differences between the three countries.

Trending Topics

VIEW ALL