NAFTA; The Three Little Pigs

TOPICS

USDA

photo credit: AFBF Photo, Cole Staudt

Veronica Nigh

Former AFBF Economist

The latest hogs and pigs report contained few surprises continuing the trend of higher numbers in 2017. Farrowing intentions continued their upward march. Producers indicated they expect to farrow 1 percent more hogs in Dec to Feb of 2017/2018 than last year. This is on the back of the last seven quarters in which the number of sows farrowed has exceeded year earlier levels, ranging from 1 to 4 percent higher compared to the corresponding quarter a year earlier.

In turn, the number of market hogs has grown at an even faster rate thanks to gains made in pigs per litter. The increase in annual pork production is expected to be over 3.5 percent in 2017. But where will all this pork go?

On the domestic side, per capita pork consumption is estimated to increase 0.3 pounds per person this year, bringing the total to 50.4 pounds per person. That puts U.S. pork consumption somewhere around 10th in the world but still far behind countries and regions such as the European Union and China. Exports of pork have been strong this year, up 9 percent year-to-date. However, even with both of these demand increases, pork stocks are still expected to rise relative to year-ago levels. USDA estimates ending stocks will be 18 percent higher in 2017 with more hogs coming to market.

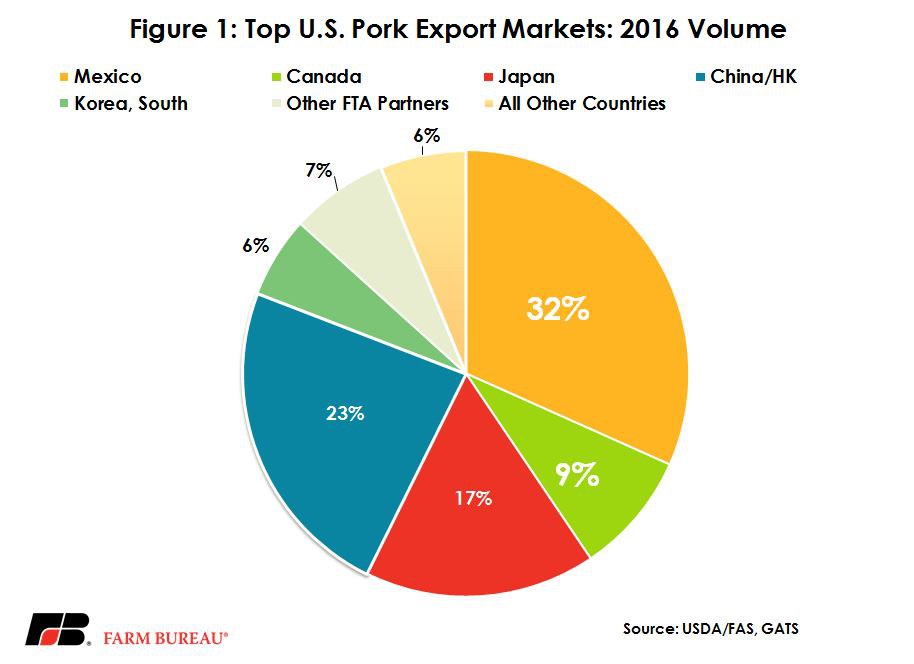

In the midst of all these increases in pork production, the NAFTA renegotiations are taking place. Mexico has been the number 1 destination for U.S. pork for the last two years, surpassing Japan in 2015. Japan was the largest pork market for more than two decades albeit Mexico was a strong number two. This year Mexico has continued to purchase high volumes of U.S. pork products, and year-to-date figures account for about 21 percent. Canada is also a strong player in the U.S. pork market, ranking number three consistently behind Japan and Mexico. Over 30 percent of exported U.S. pork trade is received by a NAFTA trading partner, and in 2015 and 2016 it was over 40 percent. Figure 1 shows the trade distribution of pork exports by country. The U.S. ships an incredible amount of pork worldwide, amounting to roughly one pig in five grown in the U.S.

FTA countries account for nearly 60 percent of U.S. export volume. In these markets, U.S. pork faces reduced tariffs compared to pork from competing nations that don’t have agreements with our partners. As a result of NAFTA, after a significant phase-in period, importers of U.S. pork in Canada and Mexico pay no tariffs. In South Korea, another important free trade agreement partner, importers of U.S. pork currently pay tariffs of 0 to 15.8 percent. This is reduced from tariffs that were as high as 30 percent before KORUS went into effect. In five years, all tariffs of U.S. pork imported into South Korea will be eliminated completely.

Compare these tariffs to two other important markets with which we do not have trade agreements. In China, U.S. pork exports face tariffs of 12 to 25 percent, in addition to a 13 percent value added tax (VAT) on most unprocessed pork products and 17 percent VAT on processed pork products. In Japan, the tariffs imported pork products face is quite significant and a bit complicated to understand due to Japan’s storied “Gate Price” system. For products subject to this system, an ad valorem tariff of 3.4 percent is applied, plus a variable, specific duty is also charged on imports below a specified threshold, with the intention of bringing the price of Japan's pork imports up to the higher domestic price. For chilled/frozen pork the gate price is applied at 524 yen per kilogram or about $2.10 per pound at current exchange rates.

However, it’s not just muscle cuts and bellies that benefit from free trade. The pork live market is also heavily intertwined. Similar to the North American cattle market, over the last 23 years the hog industries in Canada, the U.S. and Mexico have evolved based on a consistent and favorable market arrangement. Canada provides more than 5.5 million hogs, mostly weaned piglets, to the U.S. each year, accounting for the majority of live pig imports. The U.S. live hog export market is relatively small by comparison. Over the last eight years, hog exports have averaged about 40 thousand head per year. About half of these go to Mexico as breeding stock.

Canada has about 1.2 million breeding stock, and an estimated 14.1 million in total hogs as of July 1, 2017. Canada exports about 65 percent of its pork production and has similar per capita consumption figures to the U.S. Canada has built up its herd in recent years, increasing inventory steadily since 2010. However, exports of live hogs to the U.S. have been relatively stable since that time, hovering around 105,000 hogs per week.

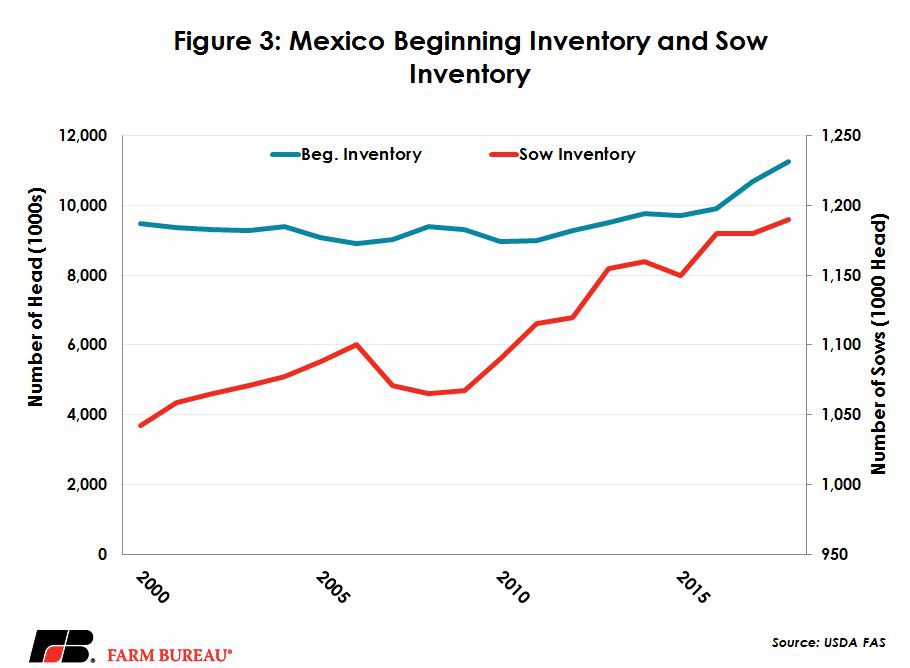

As a result of growing domestic demand, the Mexican pork industry and imports have grown. Mexico’s hog industry has expanded significantly over the last 20 plus years. Since 2000, USDA’s Foreign Agricultural Service estimates the breeding herd has grown from just over a million head to nearly 1.2 million in 2017. In 2016, imports were 45 percent of domestic consumption compared to 25 percent in 2000. Along with production and hog inventories growing, Mexico’s pork exports have also been on a steep ascent. And in 2016, USDA FAS estimates exports were 141,000 metric tons on a carcass weight, more than double the tally from 16 years ago. As an exporter, Mexico’s hog industry has a long way to go before it catches either the U.S. or Canada, but it may not be as far behind as you might think.

Relative breeding herd size suggests Canada and Mexico are neck-and-neck at about 1.2 million, while the U.S. has closer to 6 million sows. The steady improvements Mexico’s hog housing systems and the continuous improvement in genetic lines have allowed for quicker gains in production. However, the Mexican total swine numbers are below the U.S. and Canada. Mexico’s swine herd is just under 11 million this year, 3.5 million head below Canada’s herd numbers.

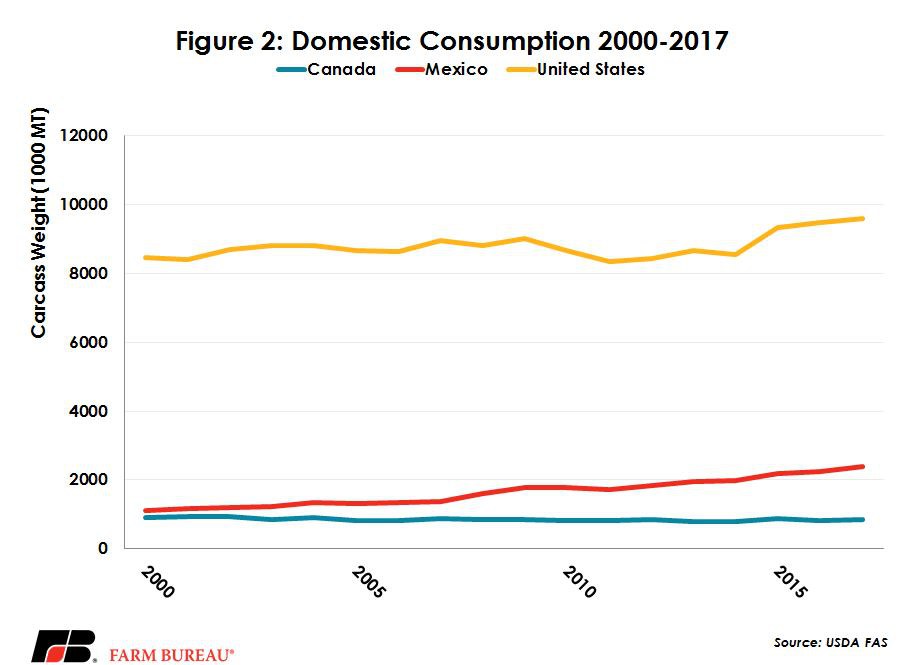

Even with Mexico’s expanding production base, nearly one of every five hogs is exported, and out of that, Canada and Mexico account for nearly half. The U.S. has been able to expand its packing capacity in the U.S. largely due to higher demand for exported product. U.S. domestic demand has grown in recent years but at nowhere near the pace seen in Mexico. There is no doubt that the loss of NAFTA would be detrimental to the U.S. hog industry, but it also has significant implications in Mexico and Canada as well. Figures 2 and 3 show the pace of domestic consumption in NAFTA countries and the rise of herd inventory in Mexico respectively.

Trending Topics

VIEW ALL