Multitude of Factors Impact US-Australia Competition in Japan

AFBF Staff

photo credit: Getty

In the wake of the Japanese safeguard tariff on U.S. frozen beef, discussions have focused on the relative change in tariff values that impact frozen beef. For those of you who may have missed it, Japan, beginning on August 1 temporarily increased the U.S. tariff on frozen beef imports from 38.5 percent to 50 percent until the end of the Japan’s fiscal year (March 31). Safeguard tariffs are implemented when the import volume exceeds a predetermined threshold.

This safeguard measure only affects countries without free trade agreements with Japan, which includes the U.S., Canada and New Zealand. Countries that have free trade agreements with Japan, such as Australia, will not experience a change in their negotiated frozen beef tariff levels. This is important because Japan is a major destination for U.S. beef, representing 20 percent of frozen exports and over 30 percent of fresh beef exports. USMEF estimates the tariff rate change will increase the price of U.S.-produced short plates by 17 cents per pound, an 8 percent increase.

The U.S. is the second largest supplier to Japan, accounting for approximately 23 percent of beef consumption while Australia is closer to 35 percent according Meat and Livestock Australia Market Snapshot. The tariff change does throw salt in the wound of the U.S. backing out of TPP and highlights the need for further work to be done to maintain market access to critical U.S. markets.

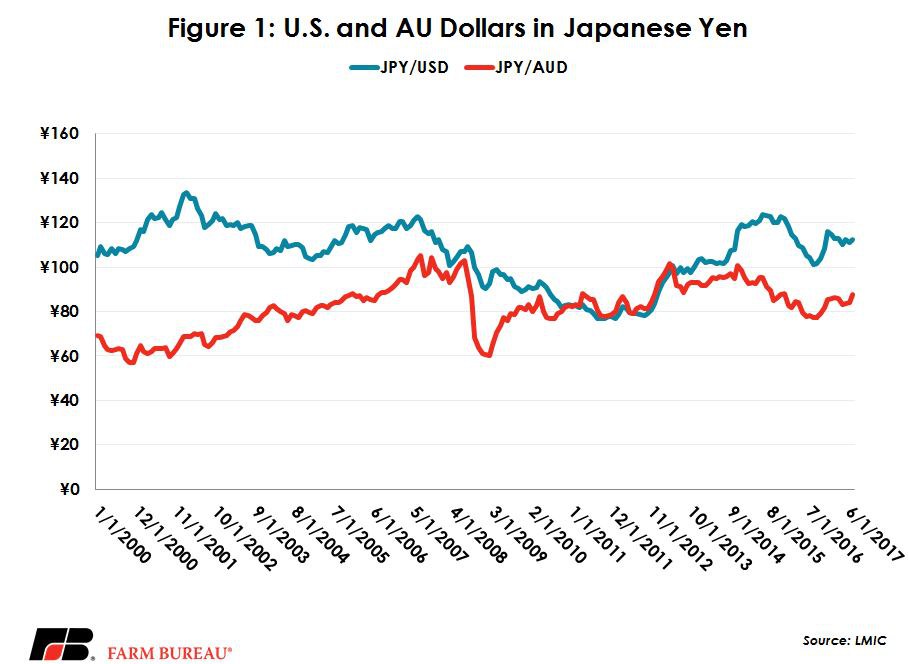

Free trade agreements offer some consistency in market access, but before we assume how much market share we will lose to Australia, we should consider all the moving parts at play. The exchange rate is a big one, but also something, that on balance hasn’t changed much in recent years. Australia has enjoyed a significant currency advantage over the last four years relative to the U.S. Figure 1 shows the Australian and U.S. dollar converted to Japanese yen. The U.S. dollar has been about 30 percent more expensive relative to Australia in 2017. Currency exchange rates go beyond affecting a specific product. They also fluctuate considerably, cannot be negotiated, and affect not only the relative value of currencies with trading partners but also competitors. Since Australia has enjoyed a significant currency advantage in the last four year, the launch of this safeguard further disadvantages U.S. frozen beef to Australian beef from a pricing standpoint. The Australian dollar was trading at $1.26 per U.S. dollar during the first week of August.

The primary loss of market share is predicted to come from U.S. short plates, a product preferred in gyuden beef bowl restaurants and heavily used by Japanese consumers. As stated above, short plate prices are predicted to rise 8 percent from the tariff increase. However, that’s not to say the value of U.S. short plates will fall to zero. Other markets could open up in the wake of Australia devoting more product to the Japanese market – creating an opportunity for the U.S. to backfill residual demand globally.

From a value perspective, short plate prices are also unlikely to fall below the price of 50 percent lean ground beef price, because there is still value in grinding the product and finding a home on the domestic market.

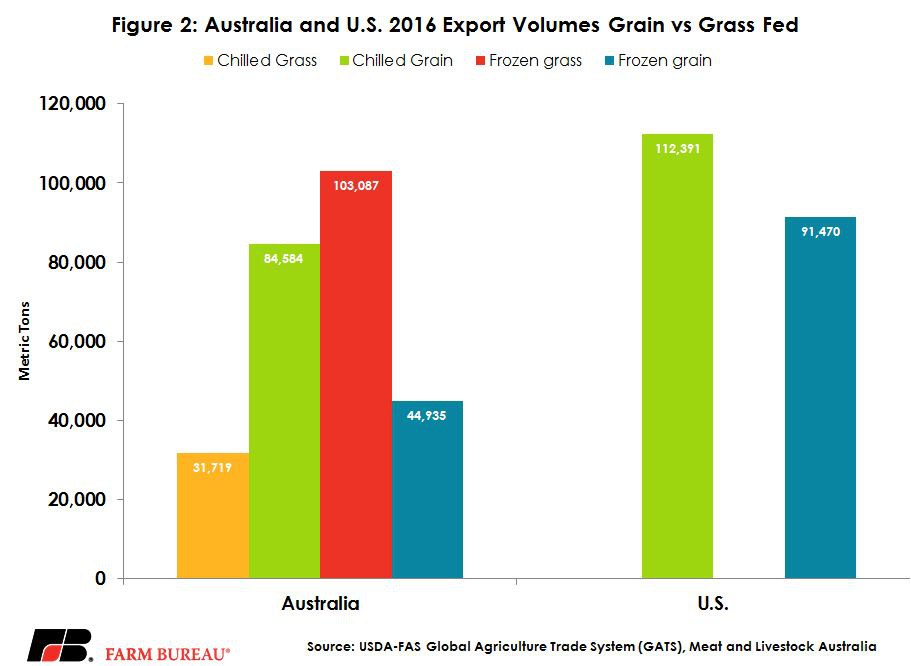

Japanese buyers also have the choice between chilled and frozen, as well as grass-fed beef and grain-fed. Japan is a much larger chilled market for Australia then frozen. Chilled product represents about 61 percent of the exports by value, compared to 39 percent frozen product according to Meat and Livestock Australia. On a volume basis, the division of grain to grass varies between chilled and frozen as well. About 32 percent of the chilled beef exported to Japan is grain-fed compared to only 17 percent of frozen beef over the 2016 calendar year. This means the U.S. shipped an additional 46 thousand metric tons of frozen grain-fed beef into Japan than Australia did in 2016. Figure 2 shows the 2016 comparison of grain-fed and grass-fed trade volumes.

Trade matters are often complicated and involve far more than supply and demand of the underlying commodity. Without question, the safeguard tariff makes U.S.-produced beef less competitive and more expensive in Japan. However, it signifies a good thing: so far during 2017, the U.S. and other countries have shipped more beef to Japan than in 2016 thereby triggering the safeguard. Year to date, U.S. exports to Japan are up 13 percent for frozen beef and 40 percent for fresh/chilled compared to last year. Variety meats are also not under safeguard measures and have also seen gains in the Japanese market. Fresh, chilled offal is up 13 percent year to date in 2017, tongues are up 22 percent, and livers are up 9 percent.

The safeguard measure is neither a positive precedent nor is it a dire setback. This safeguard is due to lift at the end of March 2018 and although fresh/chilled beef could trigger an additional safeguard measure, for now, U.S. chilled beef is enjoying a vast expansion into the Japanese market to the tune of 40 percent year to date.

Trending Topics

VIEW ALL