Market Update: Table Eggs

TOPICS

TradeAFBF Staff

photo credit: North Carolina Farm Bureau, Used with Permission

Two years after one of the worst high pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) outbreaks decimated laying flocks, egg production has recovered and prices seem to be returning to normal. This year U.S. hens will produce 8.7 billion dozen eggs. Just over 1 billion of those will go to hatcheries resulting in more chickens, but the remainder will find their way to U.S. consumers, cold storage or export markets.

Production

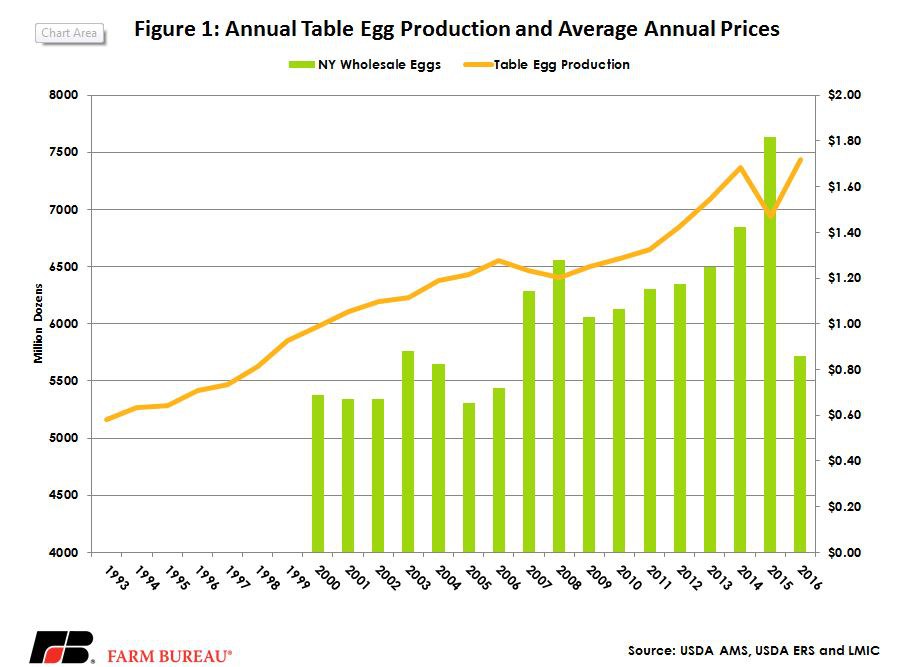

Egg production has surpassed pre-2015 levels and is sitting higher than 2014 egg production. In 2015, egg production fell by 500 million dozen as a result of lower flock numbers due to HPAI. Since 1993 the number of table eggs produced has been rapidly growing, averaging 1.7 percent a year prior to 2015. The decline in production and resulting price rally provided the boost needed to ramp up production. The following year, 2016, table egg production increased 7 percent from the year before and was up 1 percent from 2014 levels. Figure 1 shows the table egg production since 1993 and corresponding annual average prices since 2000.

Long-term, egg prices have been trending higher since 2000, when the annual average price was 68.90 cents per dozen. Egg prices remained under $1.00 per dozen until 2007, when higher feed costs pushed prices up 59 percent in a single year to $1.14 per dozen. Since then prices had been above a dollar through the late 2000s and 2010s. Avian influenza led to the second-highest jump in our price series, pushing egg prices another 28 percent higher in 2015. However, the increase in production that high prices tend to cause has led to 2016 and 2017 having the lowest egg prices in over a decade. Last year, egg prices averaged 85.93 cents per dozen and in 2017 egg prices have averaged 85.60 cents per dozen through early November.

Although production increased rapidly after HPAI hit, one of the reasons it’s taken prices so long to rebound is that higher-priced inputs pushed many food manufacturers away from egg products to substitutes. The other factor is that in response to the egg shortage the U.S. relaxed trade restrictions on imported eggs, allowing the Netherlands to ship shell eggs to the U.S. Egg imports jumped five-fold in 2015 from where they were over the last decade and 2016 maintained that high level. Imports in 2017 have slowed significantly, back to 2014 levels.

Cold Storage

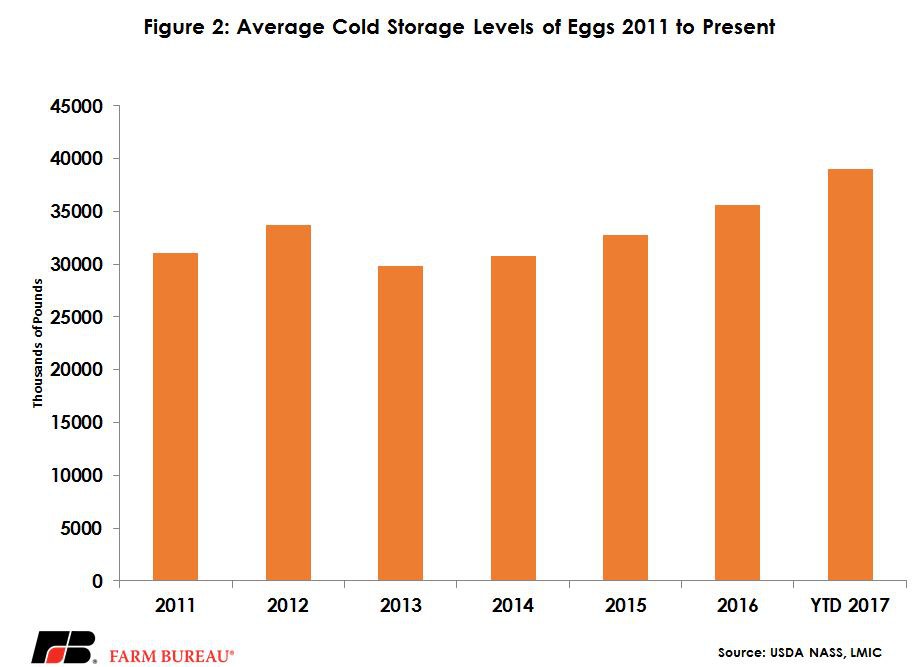

Eggs in cold storage have been slightly higher than normal this year. Over the last five years, eggs in cold storage have averaged 32 million pounds. Through the first nine months of 2017, inventories have been closer to 39 million. Some of this build up may be that food manufacturing has been slow to move back into the egg market, even with lower prices. Figure 2 shows growth in cold storage this year compared to the previous five years. Exports could potentially be contributing to the build in inventories. Egg yolks and dried egg product exports are not segmented between chicken eggs and other eggs, but those export quantities are up significantly this year. Dried egg yolks are double the shipments they were last year at this time, while fresh/chilled egg yolks are up 41 percent.

Price Outlook

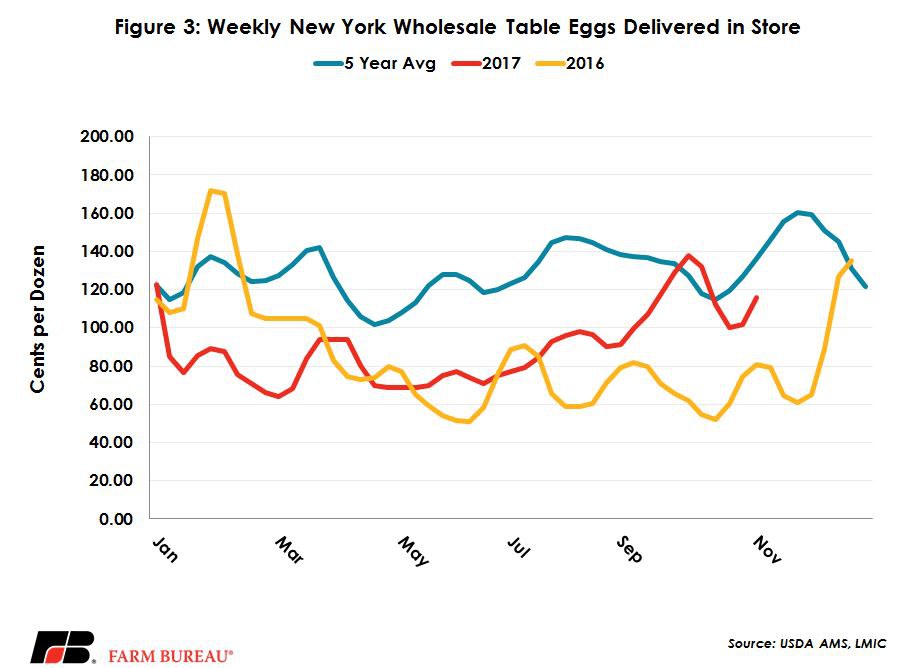

Although prices have been fairly low, late in 2017 egg prices are returning to more normal level. September wholesale egg prices averaged $1.22 per dozen, and over the last nine weeks, wholesale egg prices have been over $1 per dozen. U.S. disappearance per person has continued to grow in 2017, adding another 1 egg equivalent per person to the total of 275.7 table eggs per person per year. That number includes egg consumption in items such as baked goods, mayonnaise, ice cream and holiday favorites like eggnog. In fact, fourth quarter egg consumption is usually two-to-three eggs higher than the other quarters of the year, which is also contributing to the late price rally.

It may take a few years for egg prices to reach even pre-2015 levels consistently. Part of the reason is the supply side of the equation has caught up and grown rather quickly, while disappearance has moved slower. In 2015, table egg production fell by 5 percent, while disappearance fell by only 4 percent. In 2016, both increased by 7 percent. This year production is expected to gain another 5 percent while disappearance is expected to grow only 3 percent. A key piece to this is egg utilization in food manufacturing as a consistent source of demand for egg products. Unfortunately, there is not data that independently represents the demand from this sector but analysts rely on indicators in prices and lagged production and inventory. HPAI presents significant challenges to the supply chain for that sector and can cause disruptions that are not easily worked around in the short-term. Reformulation of baked goods is a long-term strategy that could impact future demand for eggs but that helps manage the biological challenges and risks that affect the egg supply chain. Figure 3 shows the weekly price chart for wholesale eggs in the New York market.

Trending Topics

VIEW ALL