Lesser Prairie Chicken Rule Pressures Fragile Rural Economies

photo credit: Getty

Daniel Munch

Economist

Shelby Hagenauer

Senior Director, Government Affairs

Over 18 months ago, on June 1, 2021, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) published a proposed rule in the Federal Register to list the lesser prairie chicken under the Endangered Species Act. With the final rule released, implications of the listing on agriculture in the affected region are becoming more clear. Today’s Market Intel describes some of these possible implications, which could undermine years of voluntary conservation efforts by farmers and ranchers.

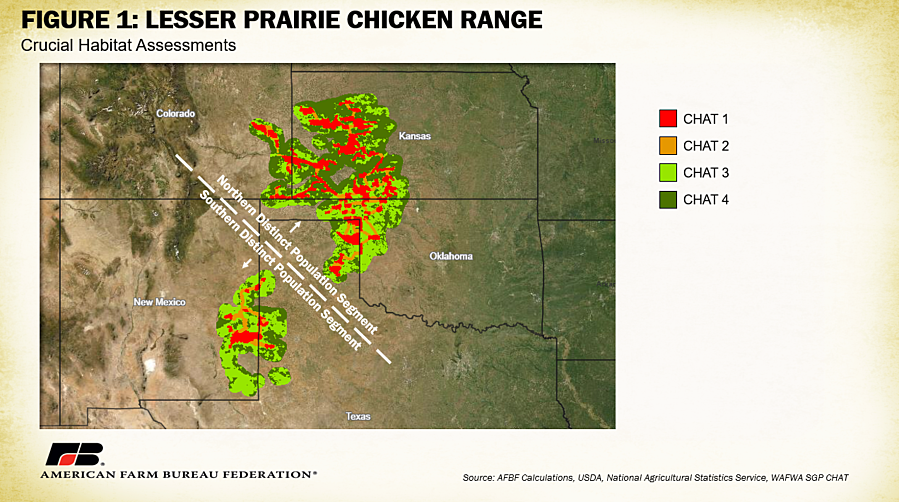

The lesser prairie chicken (LPC) is a medium-sized brown and white striped chicken-like grouse found in western Kansas, western Oklahoma, eastern New Mexico, southeastern Colorado and the Texas Panhandle. The birds inhabit shortgrass prairies and are well known for their lekking behavior in which males gather in small clearings called leks and inflate bright red air sacs in their neck and “dance.” The final rule distinguishes two populations of LPC known as distinct population segments (DPS). The Northern DPS inhabits the Texas Panhandle, Oklahoma, Kansas and Colorado and will be listed as threatened while the Southern DPS, located in West Texas and New Mexico, will be listed as endangered.

The ESA prohibits the “take” of a species listed as endangered which, under the ESA, is defined as “to harass, harm, pursue, hunt, shoot, wound, kill, trap, capture, or collect, or attempt to engage in such conduct.” The act also defines “harm” to include significant habitat modifications or degradation that “kill or injure wildlife by significantly impairing essential behavioral patterns including breeding, spawning, rearing, migrating, feeding or sheltering.” This means many human, crop and livestock interactions with a listed species could be defined as harm if determined by USFWS to be disruptive to that species.

For a species or DPS listed as threatened rather than endangered, special rules and protections are provided under section 4(d) of the ESA that can extend some or all of endangered classification protections but at varying levels. These levels are dependent on goals for a specific species’ conservation at the discretion of the director of the USFWS. Under the 4(d) rule, “take” of the Northern LPC DPS will not be prohibited if that take is incidental to agricultural practices including plowing, mowing and other mechanical manipulation of lands, routine activities that directly support cultivated agriculture and use of chemicals in direct support of agriculture when done in accordance with label recommendations on land that has been cultivated in the last five years. Producers who convert grassland into cultivated land outside this timeframe are not protected under these exceptions.

The 4(d) rule is more specific about grazing. The rule recognizes “the value that livestock grazing provides when managed compatibly and we want to encourage compatible grazing management.” However, the rule sets up a process by which ranchers must follow a site-specific grazing plan developed by a “Service-approved party.” To date, it is unclear what entities will be “Service-approved” and what the process will be for developing a new site-specific grazing plan. The rule goes into effect on Jan. 24, creating significant calendar pressures on this new process. Although criminal penalties are uncommon, violations of ESA take prohibitions can carry civil penalties of up to $25,000 per violation and criminal penalties of up to $50,000 and one-year imprisonment per violation.

The combined total value of direct agricultural receipts from crops and livestock across the five states inhabited by LPCs is nearly $55 billion or 15% of total U.S. production by value. This includes 37% ($25 billion) of the nation’s cattle and calves, 28% ($2.4 billion) of wheat and 44% ($2.6 billion) of upland cotton production by value. The LPC does not inhabit the entire area of these states, so to calculate a more precise representation of direct agriculture overlap, USDA’s National Agricultural Statistics Service’s county-by-county census of agriculture was overlaid with the Western Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies’ data on crucial habitat locations. The southern Great Plains Crucial Habitat Assessment Tool (CHAT) separates land area for LPCs into four categories. CHAT 1 areas consist of the most critical focal areas for LPC conservation and where landowners may be most likely to experience encounters. CHAT 2, 3 and 4 consist of less critical but still important land area for LPC conservation such as corridors, lek locations and general occupied range, respectively. All categories within a DPS yield ESA enforcement. Figure 1 displays the breakdown of CHAT distribution by category to show the breadth of land targeted for LPC conservation efforts. In total, over 10,000 square miles of land is designated under a CHAT 1 categorization (roughly the size of Massachusetts) and over 60,000 square miles of land is designated under any CHAT (1-4) category (roughly the size of the state of Georgia) - a significant portion of agricultural land.

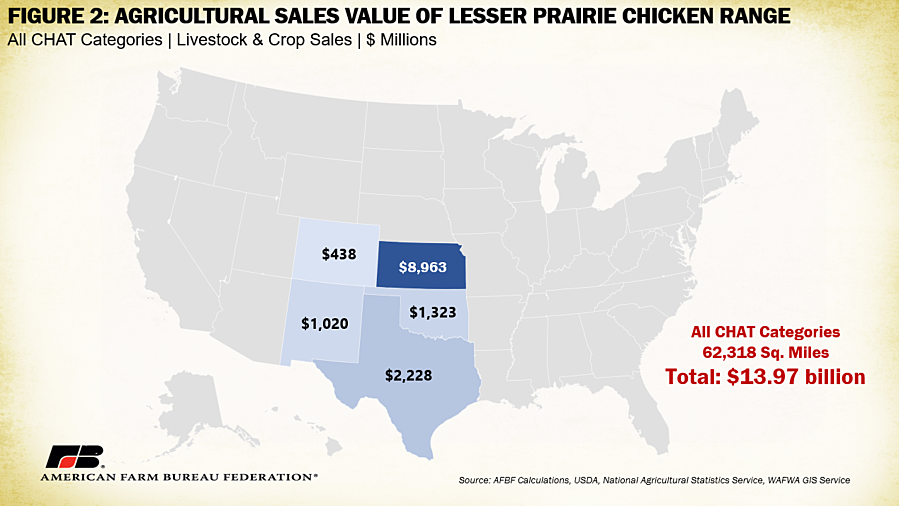

Next the percent of each county covered by CHAT 1 and CHATs 1-4 was calculated and multiplied by the agricultural sales value reported by each county under the most recent census of agriculture. For example, it was estimated that 90% of Gray County, Texas, was categorized under any CHAT (1-4) category and 32% of Gray County was categorized under the CHAT 1 category. The total value of annual animal sales in the latest ag census out of Gray County was $150 million, with 90% corresponding to a value of $135 million and 32% corresponding to a value of $48 million to estimate production value by CHAT categorization. This methodology seeks to provide an improved method of agricultural production by value overlap with an assumption that agricultural production is evenly distributed across any given county.

Figure 2 displays the value, in millions, of all agricultural sales on land categorized under all CHAT categories for the LPC. In total, nearly $14 billion in agricultural sales value occurs in the entire range of the LPC, with the bulk, or $8 billion, occurring in Kansas. Of this $14 billion figure, $10.9 billion, or 78%, comes from livestock production and the remaining $3 billion, or 22%, comes from crop production. As expected, most, or $6.9 billion, of the livestock production value is from cattle and calves.

Drilling down further, Figure 3 displays the value, in millions of all agricultural sales on land categorized under CHAT 1, or the most crucial habitat, for the LPC. In total, $3.2 billion in agricultural sales value occurs in the most critical range of the LPC, with the vast majority or $2.6 billion occurring in Kansas. Of this $3.2 billion figure, $2.6 billion, or 82%, comes from livestock production and the remaining $568 million, or 18%, comes from crop production.

The value of direct livestock and crop sales in the LPC’s range is a small piece of the broader economic impact of agriculture in this region. The bulk of these counties are rural areas reliant on food, fuel and fiber production as a primary income and employment driver. Hurdles, regulatory or otherwise, to farming or ranching diminish the economic viability of living in rural counties and can have broader impacts to the national food supply and access to it. Across Texas, New Mexico, Kansas, Oklahoma and Colorado, agriculture and its downstream economic value supports over 6.3 million jobs that paid over $307 billion in wages, which, together, contribute to a total economic output of over $1 trillion around the globe. The wide range of taxes paid by farmers, ranchers, downstream industries and their employees total over $80 billion across these states, funding vital services including local schools and public safety.

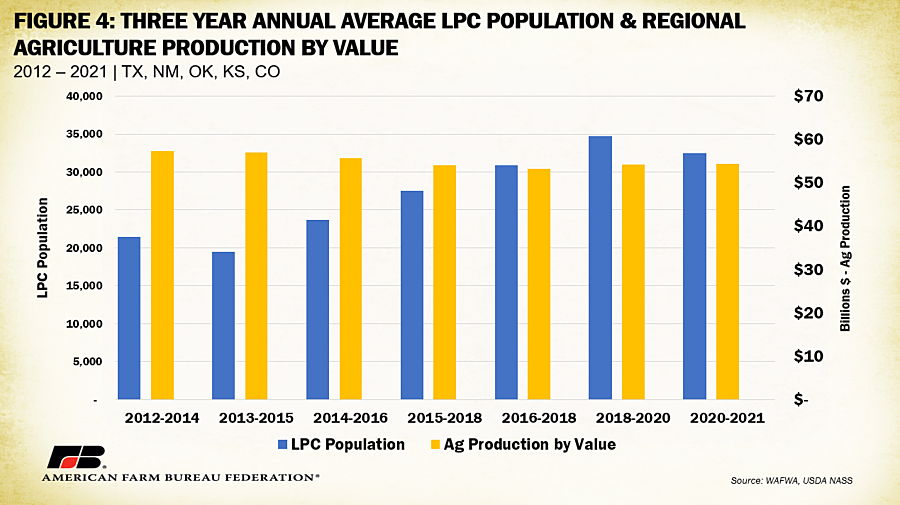

According to the latest iteration of the “Range-Wide Population Size of the Lesser Prairie Chicken 2012-2021,” the lesser prairie chicken population had been gradually increasing until 2021. Figure 4 displays the three-year annual average LPC population compared to the five-state region’s agricultural production by value.

LPC populations have increased about 50% between 2012-2014 and 2020-2021 (no surveys were completed in 2019). During the same timeframe, agricultural production by value in these states hovered around $55 billion in nominal (current) dollars. In other words, LPC populations have been able to recover by 50% while agricultural production in the region remained relatively stable. The rule admits “grazing by domestic livestock is not inherently detrimental to lesser prairie-chicken management and, in many cases, is needed to maintain appropriate vegetative structure” when appropriate grassland management approaches are followed; grazing approaches most ranchers in the region have voluntarily put into practice to improve land productivity.

As of the Jan. 19 drought monitor, 60% of the land area in Colorado, 77% of the land area in Texas, and over 90% of the land area in Kansas, New Mexico and Oklahoma is categorized under abnormally dry conditions or worse. Many counties in the states rated D3 (extreme) or D4 (exceptional) drought overlap directly with critical habitat zones for the LPC. Federally listed species that limit agricultural production in an area reeling from water deficits adds another obstacle to local farmers’ and ranchers’ ability to endure.

Conclusion

Farmers and ranchers are committed to the health of the ecosystems they rely on to grow crops and raise livestock. The families who choose to live in rural communities are often drawn by the diversity in vegetation and wildlife and the inherent role they play in stewarding the land as farmers and ranchers. With each dollar produced by an agricultural community multiplying through downstream channels into trillions in economic value, even small regulatory hurdles that harm farmers and ranchers can have a large impact well beyond rural America. The lesser prairie chicken ESA listing further stresses already fragile drought-stricken rural economies while alienating producers who have worked diligently and voluntarily on wildlife conservation projects.

What We're Saying

Hurricanes, Heat and Hardship: Counting 2024’s Crop Losses

Feb 18, 2025

READ MORE

Beef Prices Soar to Record Highs, Yet Farmers Struggle to Reap the Benefits

Aug 30, 2024

READ MORE

Improvements to Crop Productivity Critical in Western U.S.

Aug 1, 2024

READ MORE

Major Disasters and Severe Weather Caused Over $21 Billion in Crop Losses in 2023

Feb 29, 2024

READ MORE