Land Values and Cash Rents Are Higher in 2018

TOPICS

Market IntelBob Young

President

photo credit: AFBF photo/Morgan Walker

Bob Young

President

The release of the Department of Agriculture’s Land Value Survey earlier this month held relatively few surprises at the headline level. The total value of agricultural land, including buildings, was $2.7 trillion in 2018, up $59 billion, or 2 percent, from prior-year levels. Overall, average agricultural land values increased an average of 1.9 percent, up $60 per acre to $3,140 per acre. With the 2017 inflation rate running 2.1 percent, this would suggest the real price of agricultural land was unchanged for the year.

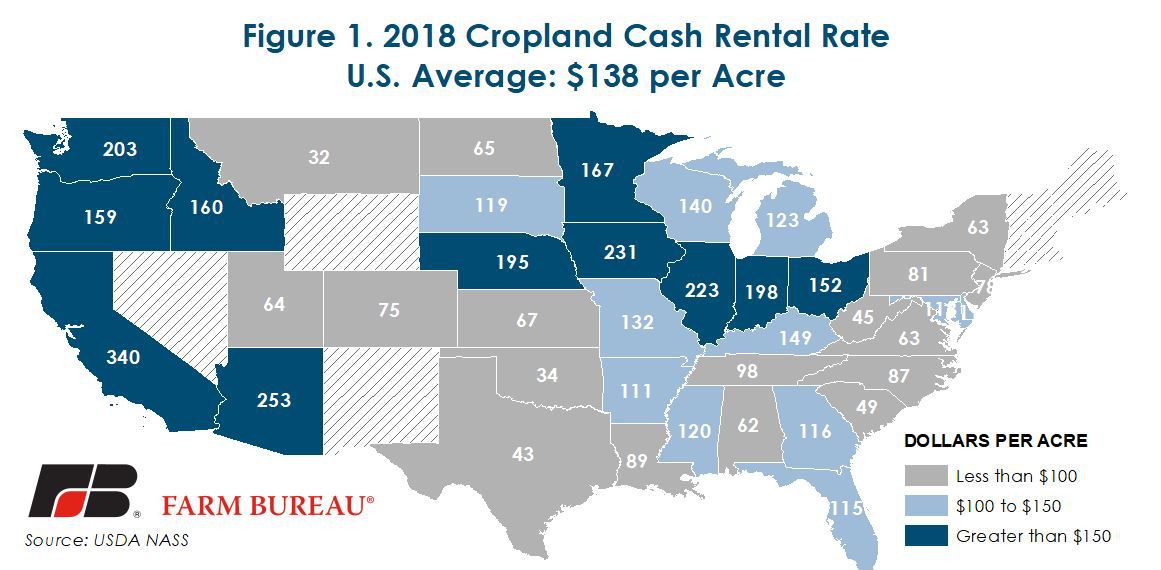

With agricultural land values rising in 2018, an increase in cash rents was not unanticipated. The national average rate moved from $136 per acre in 2017 to $138 per acre in 2018, again about the same rate as inflation. This was essentially the same rental rate as observed in 2013. While rates did bump up to a high of $144 per acre in 2015, land rent has been fairly static around this $135-to-$140-per-acre rate for the last six years. Figure 1 highlights U.S. average cash rents for cropland in 2018.

Taking the numbers apart, it is little surprise that California came in with the highest average rent – $340 per acre averaged across all land and $528 per acre for irrigated land. Corn Belt states – Nebraska, Iowa, Illinois and Indiana – all came in with rental rates near or above $200 per acre. These rates were up over the previous year’s values, even with corn and soybean prices facing significant downside pressure over the last several months.

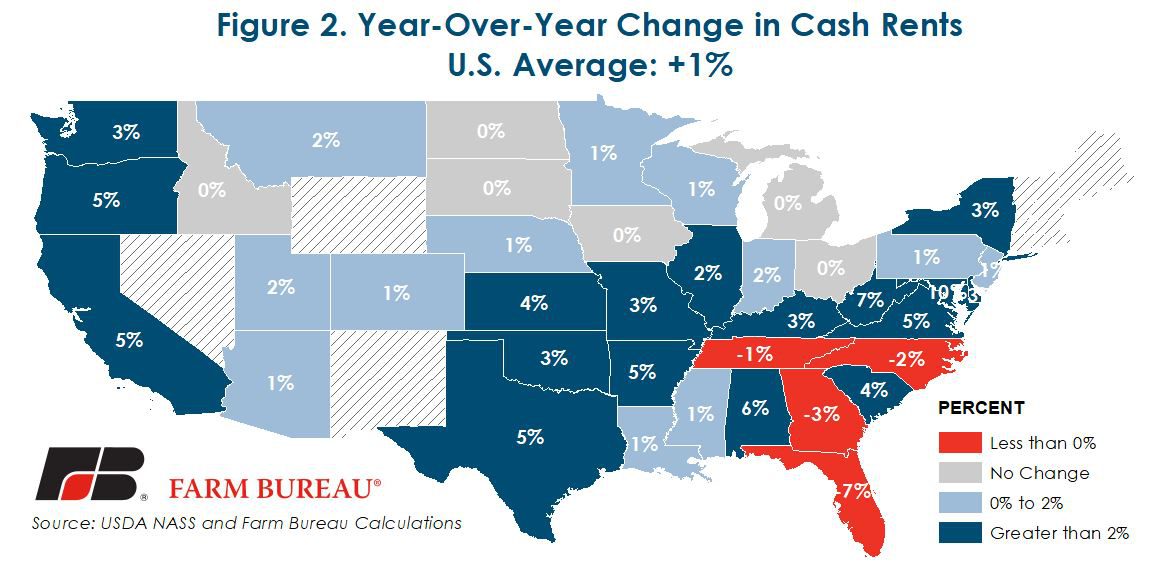

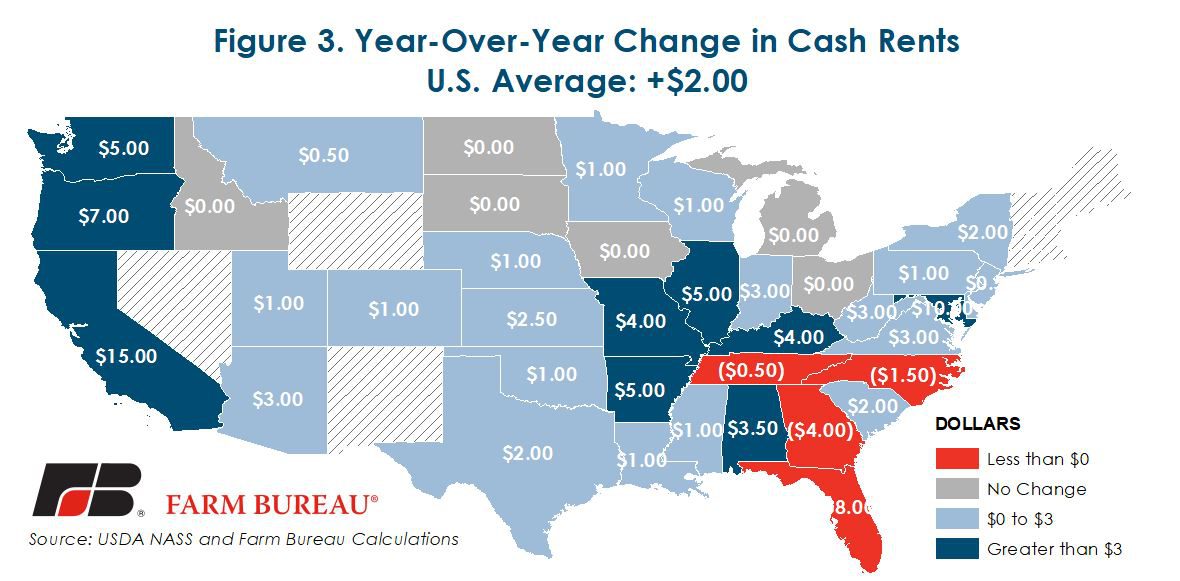

While numerous states reported 5 percent or better year-over-year gains in land rents, West Virginia showed the highest percentage increase over 2017 figures. But perspective matters. The 2017 rental rate in West Virginia was only $42 per acre and the 2018 figure came in at $45 per acre. In terms of absolute dollar change from the previous year, California again hit the top mark with rates rising by $15 per acre. Probably a fluke of numbers as much as anything else, Maryland’s rates showed the second-greatest rise, lifting by $10 per acre in 2018. Going in the other direction, Florida showed the largest year-on-year decline with rents sagging by $8 per acre. Georgia came in with the second-largest decline, dropping by $4 per acre. Figures 2 and 3 highlight the change in those cropland cash rental rates from the previous year on a percentage and absolute dollar basis, respectively.

Summary

Despite depressed commodity prices, cash rental rates for cropland increased by $2 per acre in 2018 to $138, remaining above their pre-2012 levels. The increase in cash rental rates paced with inflation and was supported by higher agricultural land values and the effects of very low interest rates. With low interest income from other sources, any kind of return from agricultural land makes it an attractive investment alternative.

How much longer can agricultural land continue to increase in value? Going back to 2000, U.S. agricultural land value and average cash rental rates have increased in 16 out of 18 years. The only years to experience a decline in agricultural land values or cash rents were 2009 and 2016. Declining revenue streams, the certainty of higher interest rates and uncertainty about the demand for U.S.-produced agricultural commodities in export markets are eventually going to weigh on land prices. Will it happen in 2019? It remains to be seen.

Trending Topics

VIEW ALL