Japan-U.S. Agriculture Agreement Could Help U.S. Catch Up to Global Competitors

TOPICS

Trade

photo credit: Dpd3ut/CC BY-SA 4.0

Veronica Nigh

Former AFBF Economist

Farmers, ranchers and many others involved in U.S. agriculture are eagerly awaiting the announcement of a mini-trade deal between the United States and Japan, a long-time, steady customer of U.S. ag products. Over the last 20 years, ag exports to Japan averaged $10.7 billion, dropped only once below $8 billion ($7.9 billion in 2005), and reached $12.9 billion in 2018.

Japan is already the fourth-largest buyer of U.S. farm and ranch goods – sometimes ranking even higher – despite the average 17.3% tariff on U.S. ag products, the result of the two countries not having a free trade agreement. Common sense dictates that if Japan’s ag tariffs were lowered, its citizens would buy more imported ag products. Eager to be the supplying country that benefits from lower tariffs relative to its competitors, several countries have sought FTAs with Japan. The U.S. is currently on the outside of those agreements and is looking to catch up.

Over the last few years, Japan has made no secret that it preferred the U.S. join the Trans-Pacific Partnership, or the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership as it became known after the U.S. withdrew from the TPP in January 2017. However, the U.S. has been resistant to this idea and instead pursued an arrangement that does not meet the comprehensive definition of a trade agreement, but that does include reductions in tariffs for U.S. agricultural products. Japan has repeatedly stated it will not give the U.S. a stand-alone deal on agriculture that would be better than what it would have received had it remained in the TPP/CPTPP. This Market Intel explores what Japan’s tariffs on U.S. agriculture would look like if we were to simply pick up where TPP left off.

CPTPP is a free trade agreement between 11 countries in the Asia-Pacific region: Australia, Brunei, Canada, Chile, Japan, Malaysia, Mexico, New Zealand, Peru, Singapore and Vietnam. The CPTPP entered into force among the first six countries to ratify the agreement – Canada, Australia, Japan, Mexico, New Zealand and Singapore – on December 30, 2018. Vietnam followed on January 14, 2019.

When the agreement went into effect, the first tariff cuts occurred. However, Japan is unique in that the government's financial year is from April 1 to March 31, which means that Japan’s tariffs were cut again on April 1, 2019, for the CPTPP members. This puts Japan in the second year of CPTPP implementation. If the new U.S.-Japan agreement goes effect by March 31, 2020, and the U.S. were to get the same tariff treatment as CPTPP members, the tariffs on U.S. products would need to be equivalent to the second year of implementation. If the agreement struck were to go into effect on April 1, 2020, or later, the tariffs on U.S. products would have to be equivalent to the third year of implementation in order for the U.S. to catch up to its CPTTP competitors.

Assuming the preferential trade arrangement for the U.S. goes into effect by March 31,, 2020, what does that mean for specific products? For some goods, the answer is fairly straight forward. For example, beef tariffs would fall from 38.5% to 26.6%. Fresh or chilled poultry tariffs would fall from 11.9% to 7.9%. Duck, geese and turkey meat would instantly be tariff-free, as would the majority of fresh vegetables. All nuts, except chestnuts and pecans, would enter Japan duty-free instantly. The tariff on fresh apples would fall from 17% to 11.4%. The tariff on cherries would fall from 8.5% to 3.4%. Fresh strawberries, raspberries, peaches and melons would all enter duty-free.

For other products, the answer is a bit more complicated. For example, Japan guaranteed more access to its CPTPP dairy suppliers through a tariff-rate quota. When the U.S. was a member of the TPP, U.S. dairy exporters would have had the opportunity to compete against Australian and New Zealand dairy companies for the quota volumes. However, in the absence of the U.S., Australian and New Zealand companies have been developing sales relationships to fill those quotas. Will Japan create separate TRQs for U.S. dairy products? A similar question exists for any product that received additional access to Japan via a TRQ, including wheat, rice and processed foods containing wheat. Finally, will Japan offer the same reductions to its complicated Gate Price System for U.S. pork as it would have under the TPP? Had the U.S. stayed in the TPP, Japan would have immediately reduced the specific duty charged on pork cuts under the Gate Price System by 74%, dropping it from the previous maximum charge of 482 yen per kilogram to 125 yen per kilogram.

These are just a few examples, but all of the commitments Japan made under the TPP are still available on the U.S. Trade Representative’s website. Simply find the HS code of interest and look in the “Year 2” column to find the tariff rate the product would be charged if the U.S. were to catch up to our CPTPP competitors.

The natural question is how quickly higher tariffs impact U.S. competitiveness. How critical is a quick, catch-up agreement with Japan? While, thus far the article has focused on the CPTPP, it’s also important to remember that the comprehensive FTA between Japan and the European Union went into effect February 1, 2019. So, while the only data available for comparisons related to the EU-Japan Economic Partnership Agreement and the CPTTP is from January-July 2019, the impact on the U.S. is already becoming evident.

Japan’s global ag imports from April through July 2019 are 8% higher than the three-year average, 2016-2018 for the same period. The months of April through July are chosen as the basis for comparison because that is when both agreements were in effect and both rounds of Japan’s tariff cuts had been made. Thankfully, Japan’s imports of agricultural products from the U.S. increased by 5.8% over the same time period. If the U.S. were looked at in isolation, it appears that thus far the FTAs to which the U.S. is not party to are having a limited impact.

However, import growth from six of the seven FTA countries has exceeded the United States’. Compared to the same time period in 2016-2018, Japan’s April-July 2019 ag imports from the EU are up 15.9%, while ag imports from Mexico, New Zealand and Canada are up 27.6%, 16.9% and 12.5%, respectively Similarly, ag imports from Australia have climbed 6.8%, followed by Singapore, which posted a 6.7% increase. Only Vietnam has trailed the U.S. Still, the U.S. remains the largest ag exporter to Japan, with a 23% market share, though the EU is picking up the pace and now commands an 18% market share.

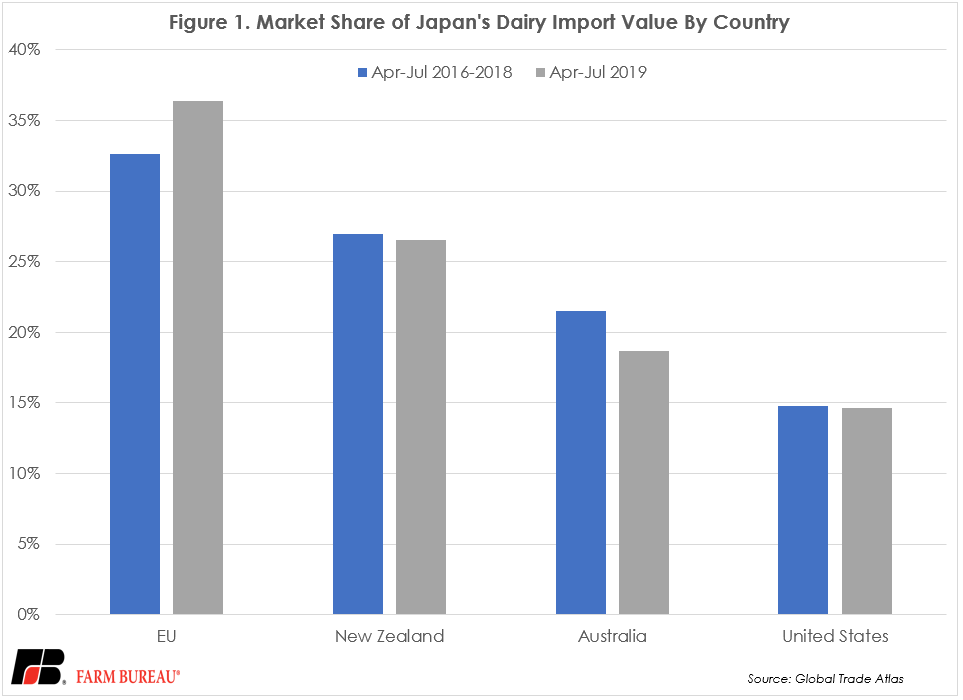

Overall numbers can mute more dramatic trends on a product-by-product basis. In the dairy case, Japan’s global dairy imports are up 16%, while imports from the EU are up 29% in the April-July 2019 period, compared to the same time period in 2016-2018. The EU has already increased its market share by 3 percentage points, while U.S. market share has remained steady as seen in Figure 1.

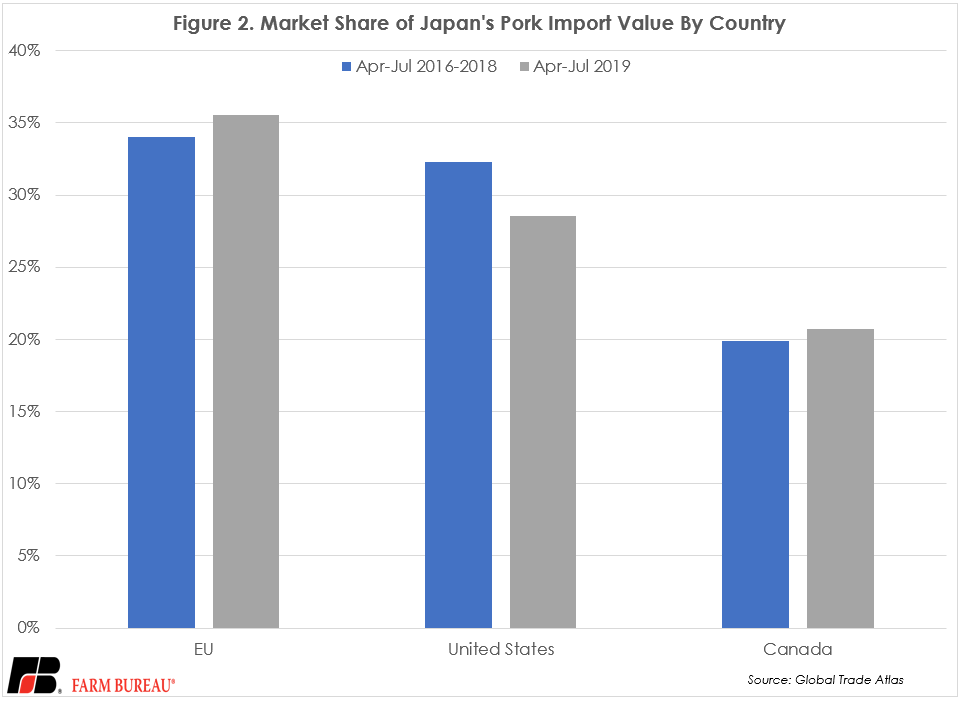

A similar story can be told for U.S. pork. Japan’s global pork imports are up 12%, with imports from the EU up 17% and imports from the U.S. down 1% in the April-July 2019 period, compared to the same time period in 2016-2018. During this time period, the EU market share has increased by 1.5 percentage points, Mexican market share has increased by 1.6 percentage points and Canadian market share has increased by 0.8 percentage point, while U.S. market share has fallen by 3.7 percentage points, as seen in Figure 2.

Conclusion

Significant tariff reductions can swiftly impact the market share U.S. agriculture commands in an export market. The U.S. saw its market share slip away quickly when passage of the US-Colombia FTA was delayed, while the Canada-Colombia FTA went into effect. While the CPTTP and EU-Japan Economic Partnership Agreement are still in the first few months of implementation, early data suggests that U.S. market share is susceptible to erosion as our competitors enjoy lower tariffs. An agreement between the U.S. and Japan that would put the U.S. on par with our competitors would be most welcome.

Trending Topics

VIEW ALL