Is it too Late for U.S. to be Crowned “Soybean King”?

photo credit: Getty

John Newton, Ph.D.

Former AFBF Economist

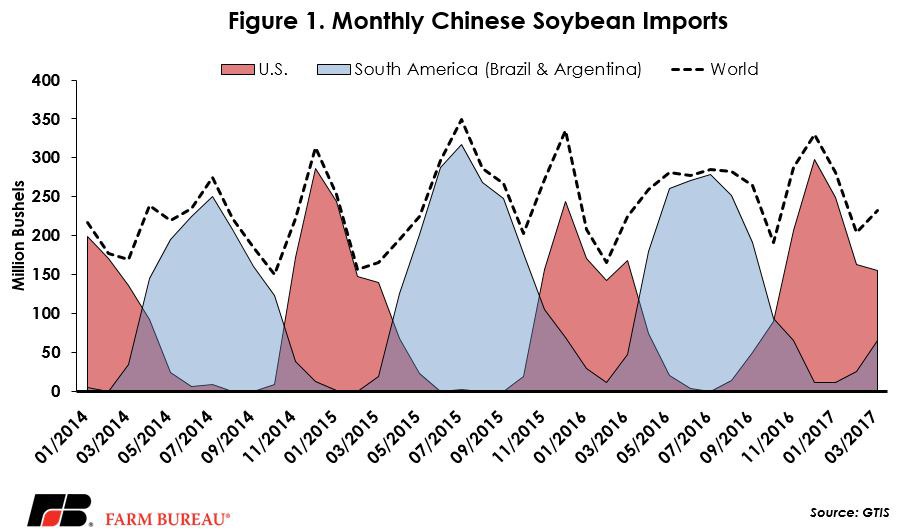

There is no question that one of the big winners in the growth in demand for soybeans from China has been U.S. soybean producers. A recent Market Intel article, China’s Insatiable Demand for Soybeans, highlighted the growth in U.S. exports to China since China joined the World Trade Organization in 2001. Each month China imports hundreds of millions of bushels of soybeans and soy by-products, not only from the U.S. but from Brazil and from Argentina as well. Figure 1 highlights the seasonal nature of China’s soybean purchases from the U.S. and South America. The big winners in the rush to satisfy Chinese demand are clearly U.S. farmers, but another big winner is hot on our heels … South America.

Chinese Demand Led to Growth in Soy Production

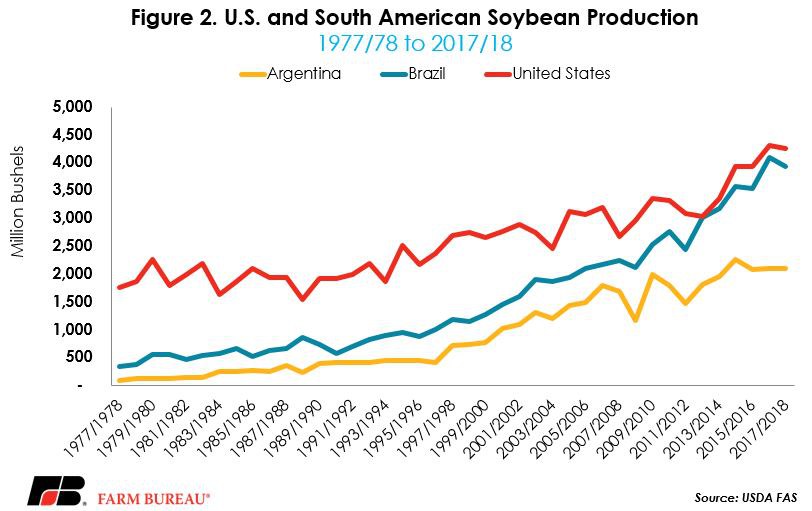

Thanks to Chinese demand, South American soybean production will be record-large in 2016/17. USDA’s May 10 World Agricultural Supply and Demand Estimates project Brazil’s soybean production in 2016/17 to total 4.1 billion bushels, up 16 percent from prior years. Argentina’s soybean production is projected at 2.1 billion bushels, up less than 1 percent from 2015/16 levels. Combined, soybean production in Brazil and Argentina is projected at a record 6.195 billion bushels, up 10 percent from last year. While it remains early, USDA currently projects South American soybean production to fall slightly in 2017/18 to 6.026 billion bushels (figure 2). No change is projected for Argentina, while Brazil soybean production is expected to fall 4 percent to 3.9 billion bushels.

In 2001, Brazil harvested 40 million acres and Argentina harvested 28 million acres of soybeans. Since 2001, harvested area in Brazil and Argentina has grown 108 percent and 65 percent, respectively. In 2016/17 Brazil will harvest 84 million acres and Argentina will harvest 46 million acres. Meanwhile, while Brazil and Argentina have experienced substantial growth in soybean harvested area, the U.S. has expanded soybean harvested area by only 13 percent – from 73 million acres to 83 million acres. This substantial growth has been possible by bringing new acres into production in South America, while U.S. crops must bid for existing acres.

In the U.S., much of the growth of U.S. soybean production has come at the expense of wheat acreage. In the 1996 crop year, 34 percent of the combined corn, soybeans and wheat acreage was planted to wheat. Now, USDA’s March 2017 Prospective Plantings report revealed that for the 2017/18 crop year wheat acres will represent 20 percent of the combined area planted to all three crops. Corn has consistently represented 40 percent of the total combined area, and soybeans have grown from 64 million acres in 1996/97 to nearly 90 million acres for the upcoming crop year – 40 percent of the combined area.

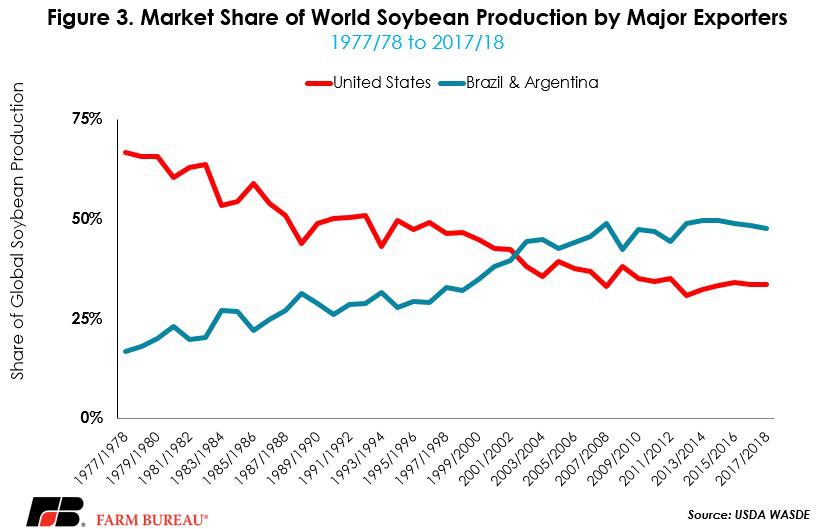

While U.S. farmers have significantly expanded soybean acreage in the last 20 years, a legitimate question is: “Did the U.S. expand too slowly?” In the late 1970s, U.S. farmers produced nearly 70 percent of the total world supply of soybeans. Brazil and Argentina combined to represent less than 20 percent of the global supply. Fast forward to 2017/18, and the U.S. market share is substantially different. While we are producing more than 4 billion bushels each year, our market share has dropped to 34 percent. Meanwhile, the combined market share of Brazil and Argentina has climbed to nearly 50 percent (figure 3).

Structural Difference in Markets

One key factor to all this growth is the rate at which expansion and productivity can happen. Relative to the U.S., land in South America is inexpensive and more readily available to farmers. In the U.S. transportation infrastructure and access to equipment manufacturing has been longstanding. In many parts of South America, infrastructure has had to expand with the growth in production acres. Equipment manufacturers also continue to advance their presence on South American soil, where demand still outpaces supply. Further, while commercial varieties are commonplace in the U.S., widespread adoption of commercial seeds is now boosting production in South America as well. This combination of factors lends itself to the rapid rise of South America as a global supplier for soybeans. This type of growth would not have been as easily advanced in the U.S. because many of these factors to production were already in place, and so acreage reallocations were not as significant.

In the U.S., corn often has a higher revenue per acre than many other crops and provides more certainty when receiving lines of credit and negotiating cash rents. Additional advantages to following corn with corn in rotation is less of a yield drag. Cotton and corn have similar rotational benefits. In brief periods soybeans may show better profitability in certain areas, but that seldom lasts long enough to permanently move acres. Corn remains "king" for these reasons in addition to the higher yield ratio in some Corn Belt states.

U.S. growers do not have a substantial yield advantage in soybeans like we experience in corn. Thus, we can’t outproduce the rest of the world on a per acre basis when it comes to soybeans. As a result, these are acres and market shares that U.S. farmers are unlikely to ever get back. When the world, China in particular, was asking for soybeans, soy oil, or soybean meal, market signals in the U.S. were partially muted. Signals were muted because as China was increasing their import demands, U.S. farmers were also responding to increased domestic demand for corn and record high corn prices. These economic factors kept corn as a profitable alternative to increasing soybean acreage. Instead of planting fewer corn acres and wheat acres, growers planted fewer wheat acres, but not at a rapid enough pace to meet the growing global demand for soy.

China buys more than 2 billion bushels of soybeans each year. Using the 2016/17 average soybean yield of 50 bushels per acre in Brazil and the U.S., China’s demand is equivalent to 40 million acres. It’s unlikely all of those acres would be in the U.S. had both corn and wheat acres been reduced to make room for soy. The economic and agronomic benefits of crop rotations identified earlier, per acre returns, and risk diversification are important in understanding U.S. planting decisions.

What’s more is that the U.S., Brazil and Argentina production systems have deep roots in relative competitive advantage and policy choices whose effects linger for decades. It becomes complicated rather quickly to discuss the intricacies, but more pragmatically farmers identify with those crops they have historically grown. Corn has long been king in the U.S. In South America corn tends to be the residual crop. However, the rapid rise in South American soy production points to the market share U.S. farmers may have had the opportunity to capture.

U.S. a “Soybean King”?

For the first time since the payment-in-kind program, U.S. soybean acres could exceed corn acres planted in 2017/18. There is currently a 514 thousand acre difference in favor of corn acres planted in 2017/18. The pace of planting and weather conditions will be key factors to monitor to determine if soybeans will overtake corn this year. However, had the market signals been a little louder in the early 2000s, the U.S. could have been “king soybean” a long time ago – but we’re almost there today.

Trending Topics

VIEW ALL