Fruits of the NAFTA Vine

TOPICS

NAFTA

photo credit: AFBF Photo, Mike Tomko

Veronica Nigh

Former AFBF Economist

When discussing the impact that the North American Free Trade Agreement has had on U.S. agriculture, the general summary has been, “the agreement has been wonderful for U.S. agriculture, with a few exceptions.” The two sectors that are often referred to here are vegetables and fruits. A review of the impact of NAFTA on vegetable trade was provided in a recent Market Intel article, NAFTA: Veggie Tales. Now, we turn to fruits and nuts.

Like many other commodities discussed in this series, in terms of trade of fresh and frozen fruits, NAFTA partners are each other’s primary trading partners, though trade isn’t nearly as concentrated as it is in vegetable trade.

In 1993, the year before the agreement went into effect, Mexico supplied 18 percent of U.S. fruit and nut imports and Canada supplied 2 percent. Throughout the implementation of NAFTA, Mexico’s share of U.S. fruit and nut imports have grown significantly, while Canada has remained relatively stable. In 2016, Mexico supplied 39 percent of all U.S. fruit imports and Canada supplied 2 percent.

Likewise, over the last several years the U.S. (45 to 50 percent) and Mexico (10 to 15 percent) have combined to supply a significant share of Canada’s fresh and frozen fruit and nut imports. This is up some from 1995, the first year for which data is available when the U.S. (53 percent) and Mexico (5 percent) combined to supply 58 percent.

The U.S. is far and away Mexico’s preferred source for fresh and frozen fruits and nuts. Over the last several years, the U.S. has regularly supplied 80 to 83 percent of Mexico’s imported fruit. This is little changed from 1995, when the U.S. supplied 77 percent.

On the export side of the ledger, the U.S. is a critical market for Mexican and Canadian fruit and nut exports. Over the last few years, 83 to 86 percent of Mexico’s fruit and nut exports were destined for the U.S. Similarly, 70 to 72 percent of Canada’s exported fruits and nuts made their way to the U.S. Meanwhile, 17 to 18 percent and 5 to 6 percent of U.S. fruit and nut exports were to Canada and Mexico, respectively. From this, we take away that the U.S. is a far more critical export destination for Canada and Mexico than Canada and Mexico are for the U.S.

The evidence above confirms the long-held belief that the U.S. runs a trade deficit with our NAFTA partners in the trade of fruits and nuts. This deficit has grown significantly on the back of a few select crops, whose popularity has skyrocketed over time. These commodities are reviewed below.

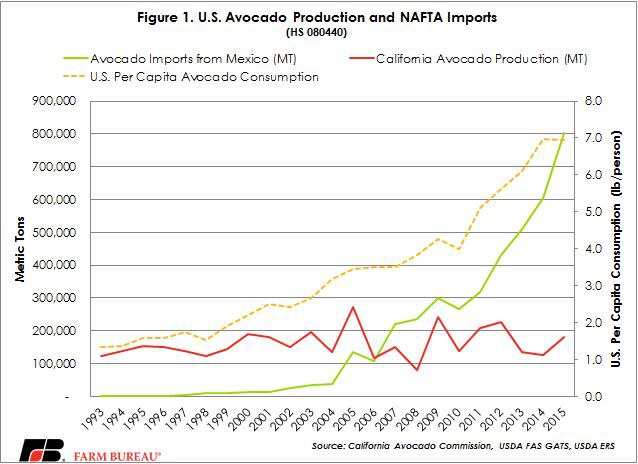

Americans Discover Guacamole

A little over a decade ago, the United States decided it liked avocados. Actually, a little over a decade ago the United States decided it loved avocados. In 1993, the year before NAFTA was enacted, U.S. per capita consumption of avocados was 1.3 pounds. By 2007, when imports of avocados from Mexico began to take off, per capita consumption had reached 3.5 pounds. By 2015, per capita consumption had climbed to 6.9 pounds and doesn’t seem to be slowing down. This meteoric rise is illustrated in figure 1.

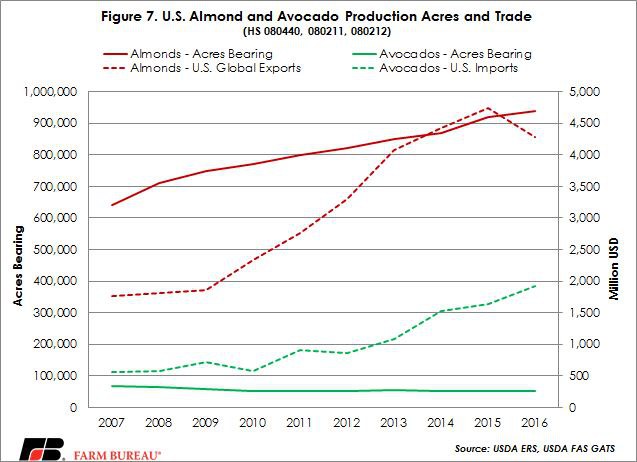

The question then is: if Americans like avocados so much, why aren’t we growing more of them here? The answer involves trade-offs, seasonality and the highest and best use of California farmland. As a starting point, it is important to remember that both avocados and almonds grow on trees and require a large investment and many years of growth before a farmer begins to reap production benefits.

Back in the mid-2000s, around the same time Americans were discovering their love for avocados, the rest of the world was discovering their taste for U.S. almonds. Given dueling demand, California farmers, who grew about 90 percent of the nation's avocado crop and nearly 100 percent of the nation’s almond crop, had to decide whether to plant more avocado or almond trees. They chose to invest more in almonds, given that the state’s climate is uniquely capable of growing excellent almonds (today, California grows more than 80 percent of the world’s supply), while Mexico’s climate is uniquely capable of growing avocados year-round (which California’s is not).

Until researchers develop an avocado variety that will grow year-round in California’s climate, the trend of Mexico growing avocados for the U.S., and the U.S. growing almonds for the world will likely continue.

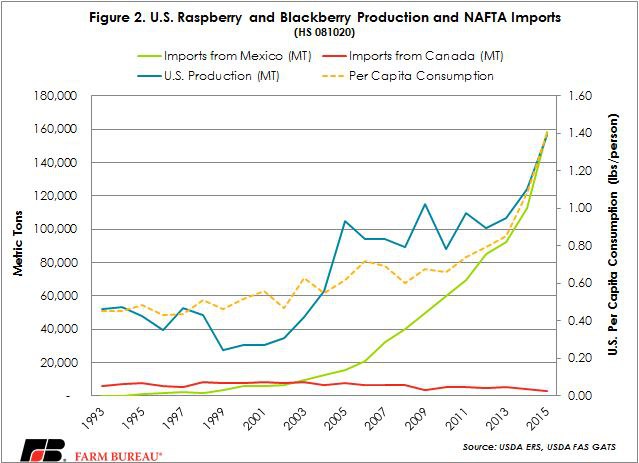

Raspberries and Blackberries

Over the last 25 years, the U.S. consumer has also developed a taste for blackberries and raspberries. Back in 1993, per capita consumption was less than one-half of a pound, but by 2015, that figure had grown to 1.4 pounds per capita. When increased per capita consumption of nearly a pound is combined with a rising population, a lot more berries are required. In fact, the U.S. consumed 331 million pounds more raspberries and blackberries in 2015 than in 1993, up 282 percent. In response to this growing demand, U.S. production, as well as imports from Mexico, grew substantially, as highlighted in figure 2.

Other Prominent Imports

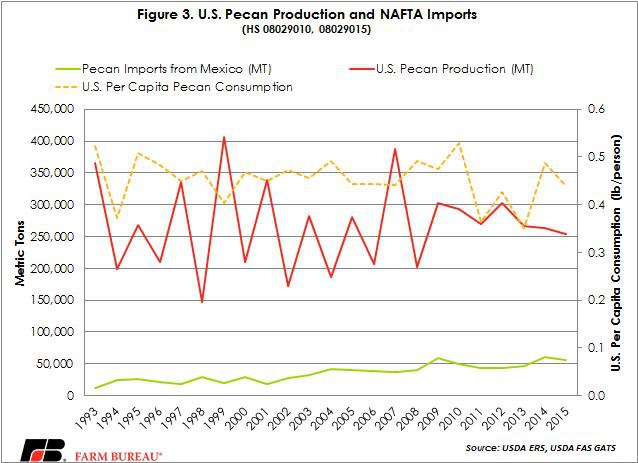

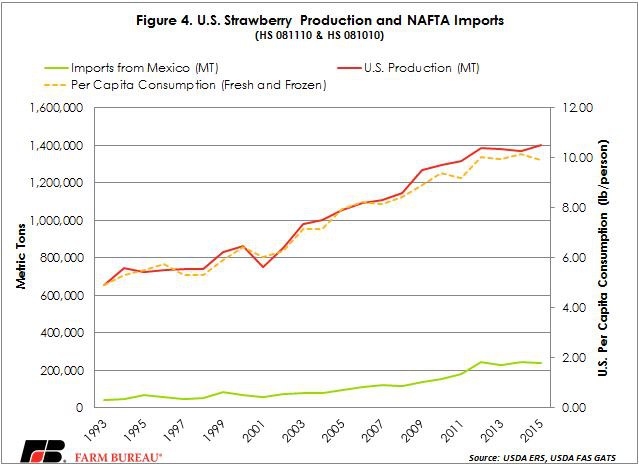

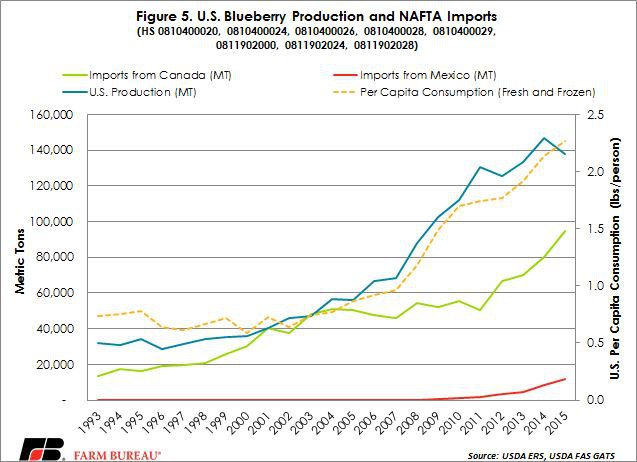

Similar to trade in vegetables, U.S. fruit and nut imports are concentrated in a handful of crops. The top two crops, described above, account for more than 41 percent of total NAFTA fruit and nut imports. Pecans, fresh strawberries and fresh lemons and limes round out the top five. The top five combine for 65 percent of total NAFTA fruit and nut imports. Figures 3 and 4 depict the U.S. production, consumption and NAFTA imports for pecans and strawberries, the third and fourth most imported crops. Figure 5 presents a similar set of facts for trade in blueberries, a crop that has been prominent in NAFTA discussions thus far.

Exports

The U.S. exports a significant amount of fresh, frozen and preserved fruits and nuts to our NAFTA partners. The top exported crop is fresh apples, which were covered several weeks ago on Market Intel, U.S. Apples and NAFTA.

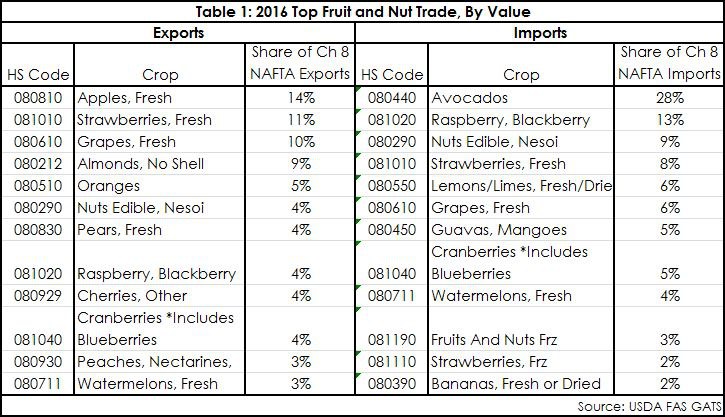

The second highest fruit and nut export item in 2016 was fresh strawberries, which primarily travel north to Canada. Fresh grapes, shelled almonds and fresh oranges round out the top five. Combined, these five crops accounted for more than 50 percent of U.S. exports to NAFTA partners in 2016. The full top exported and imported product list can be found in table 1.

Bottom Line

While the value of U.S. fruit and nut exports to the seventh (Canada) and 21st (Mexico) largest import destinations grew 229 percent between 1993 and 2016, the import of fruits and nuts into the world’s largest importer grew even faster.

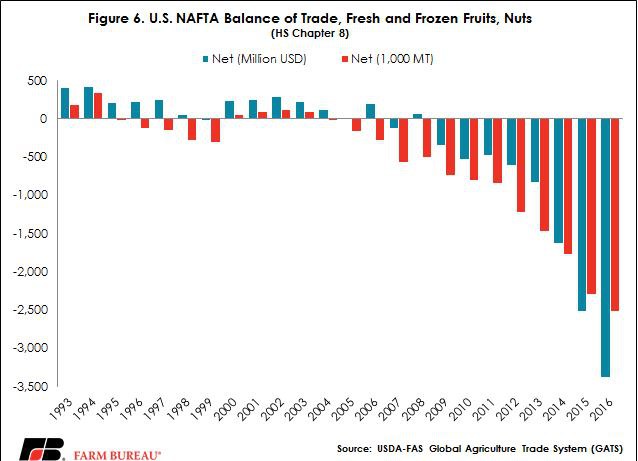

U.S. imports of fresh, frozen and preserved fruits and nuts from our NAFTA partners have grown dramatically since the implementation of NAFTA – by more than 1,100 percent. As such, the U.S. trade deficit in fruits and nuts has also continued to grow. The U.S. had a positive trade balance of $400 million in 1993. In 2016, that balance had turned negative to the tune of $3.4 billion, highlighted in figure 6.

However, one would be wise to consider what specialization among partners allows us to achieve within our NAFTA borders and beyond, figure 7.

Trending Topics

VIEW ALL