Federal Order Pool Losses Continue from 2018 Farm Bill Formula Change

photo credit: Getty

Daniel Munch

Economist

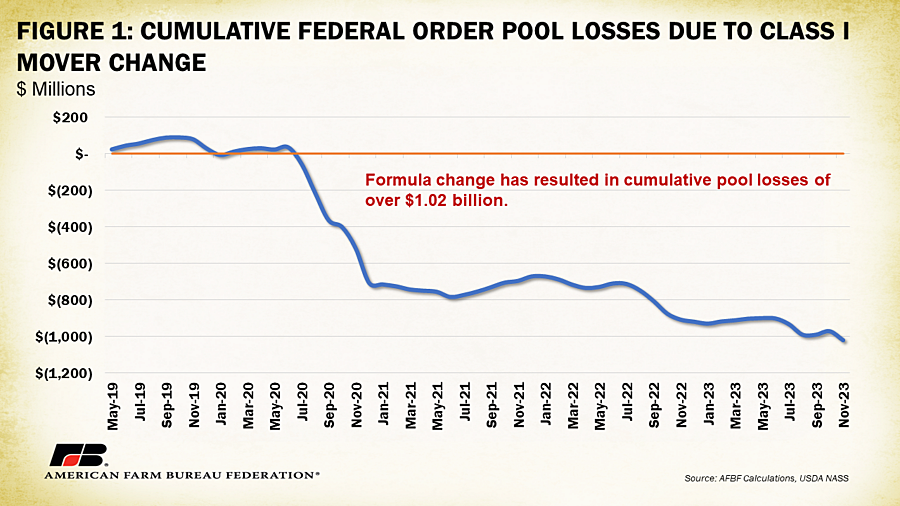

Since May 2019, the price for Class I milk, i.e., milk used to produce beverage milk products, has been calculated using the simple average of advanced Class III (cheese) and Class IV (milk powders) skim milk prices plus 74 cents. In years prior, the formula was the “higher-of” advanced Class III and Class IV skim milk prices. Milk marketing conditions, starting with COVID-19-induced disruptions, have since resulted in continued revenue pool losses linked to the formula switch. In November 2023, cumulative pool losses since the formula change passed $1 billion. With no immediate changes in sight from the ongoing Federal Milk Marketing Order hearing or in renewed farm bill discussions, dairy farmers continue to feel the impacts of diminished pool values and outdated pricing regulations. Today’s article reviews the latest dairy market and pricing policy information contributing to uncertain milk checks as we start 2024.

The 2018 farm bill included a small provision that swapped the “higher-of” formula for the simple average-of advanced Class III and IV skim milk prices plus 74 cents. The change was made at the request of dairy processors and dairy cooperatives and was intended as a revenue-neutral way to improve risk management opportunities for beverage milk. Under the classified dairy pricing system, handlers participating in an order have a payment obligation to – or a draw from – the revenue pool of federal orders. In a simple sense, the value of the four classes of milk participating in the order is combined or “pooled” together so that farmers in the region are paid the same minimum price for their milk. In this manner, for example, milk that is worth more because of a hypothetical higher current value of fluid milk offsets milk that is worth less because of a hypothetical lower cost of milk going into cheese production. The milk going into both products is essentially the same, so farmers should receive a similar price regardless of the final use.

Only Class I handlers are required to pool their milk every month. Class II, III and IV handlers can remove their milk from the order, or “de-pool,” in certain months if they so desire. Different orders have different regulations governing how and at what pace handlers can re-pool milk on the order if they decide to not participate. If a handler de-pools higher-valued milk, it leaves less value to be divided and paid to producers whose milk remains in the pool. This situation creates “pool losses” where dairy farmers with pooled milk are paid less than they would have had the additional milk value remained. When there is not enough value in the pool to cover the calculated component values (butterfat, protein, other solids) in dairy farmers’ milk, it results in deductions on milk checks known as negative producer price differentials (PPDs).

While dairy farmers were generally spared from negative PPDs throughout 2023, the Class I pricing formula change continues to result in lower values being paid to producers with pooled milk. In November 2023, pool losses due to the formula switch reached nearly $50 million. Combining this with all other losses from previous months brings cumulative pool losses due to the formula switch to over $1.02 billion since May 2019.

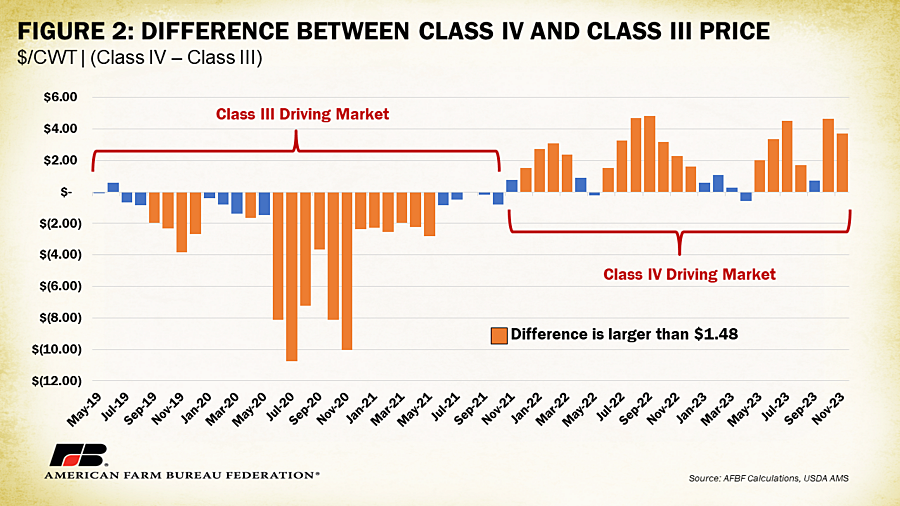

A large contributor to the continued pool losses is a persistent large spread between Class III (cheese) and Class IV (butter and powders) prices. The current “average-of” formula smooths the difference between the two values while the “higher-of” uses the simple higher of between the two options. In this manner, when the two prices differ more than $1.48 (twice the 74-cent mover) the “average-of” formula becomes less advantageous to manufactured product handlers looking to receive a higher value for their milk, incentivizing them to de-pool their higher valued Class III or IV milk and avoid pooling obligations that could reduce their overall revenue potential.

Between May 2019 and October 2021 Class III prices were driving much of the dairy market atop cheese-related supply disruptions during the pandemic. During those 30 months, the spread from Class IV exceeded $1.48 on 17 occasions or 57% of the time. This means Class III handlers were heavily incentivized to de-pool to retain higher values of their milk during this period. Since October 2021, however, Class IV prices have exceeded Class III prices. Of the 25 months between November 2021 and November 2023, the spread from Class III exceeded $1.48 on 17 occasions as well, or 68% of the time. Thus, Class IV handlers have been heavily incentivized to de-pool the past two years.

Indeed, since 2020, average monthly de-pooled milk has exceeded 20% across all federal orders (compared to an average 12% between 2016 and 2019). The 74-cent mover originally included to buffer against price spreads has failed to do so. Additionally, the upside of the formula to farmers is limited to the 74-cents-per-hundredweight mover, while the downside is unlimited. For now, the “average-of” formula remains a culprit behind lower milk checks for farmers with pooled milk. Other pricing dynamics, such as the use of advanced pricing and outdated price differentials, also play a role in what are considered disorderly marketing conditions. AFBF has targeted these factors and others that have resulted in excessive price volatility in its Federal Milk Marketing Order reform efforts.

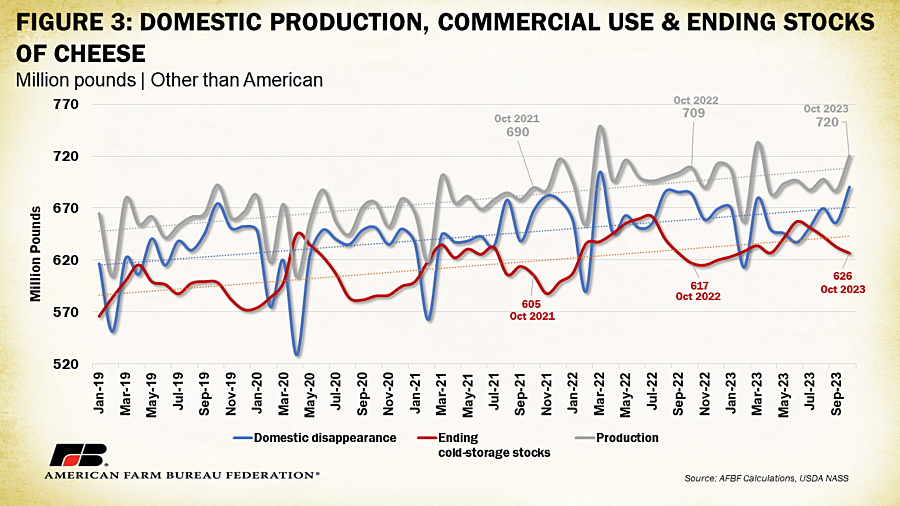

Part of the reason behind continued large spreads between Class III and IV prices is a growing stockpile of cheese stocks creating downward pressure on cheese prices that has not occurred with Class IV products. Combined with production from a myriad of new cheese plants across the nation and imports, increases in domestic consumption have not been enough to eat into cold storage stocks and bolster prices. Domestic production in October 2021 was 690 million pounds. In October 2022, this increased to 709 million pounds and has grown to 720 million pounds (for an increase of 4.4% across this three-year term), as of October 2023. Ending cold storage stocks in October 2021 sat at 605 million pounds. In October 2022 this increased to 617 million pounds and had grown to 626 million pounds (for an increase of 3.5% across this three-year term) by October 2023. Production continues to outpace consumption as reflected in these values, weakening the strength of cheese prices.

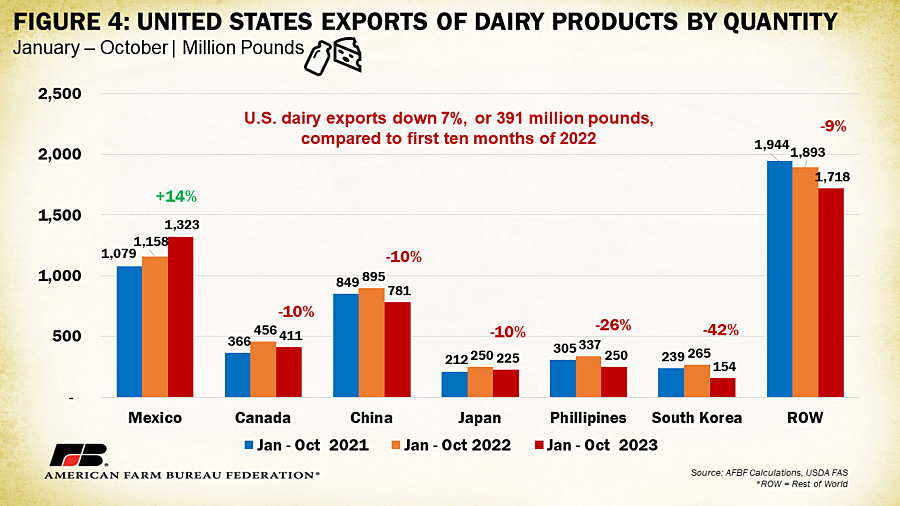

As mentioned in previous dairy market analyses, in periods of excess supply, the hope is that export markets can soak up the difference. This was the case in 2021 when exports of dairy products in the first half of the year exceeded the prior three-year average by 14% or 365 million pounds of dairy products. It was also the case in the first half of 2022, when dairy product exports surpassed 2021 levels by 119 million pounds (4%). 2023 was a different story.

Between January and October, exports dropped 391 million pounds (7%) in terms of quantity and $1.25 billion (16%) in terms of value compared to the same 10-month period in 2022. Demand in places such as Southeast Asia has continued to be more depressed than expected. U.S. exports in terms of volume for the first 10 months of 2023 were down 13% in China, 10% in Japan, 26% in the Philippines, and 42% in South Korea. These countries all sit in the top seven of dairy product export markets for the United States.

In addition, exports to our northern neighbor and second-largest market, Canada, slumped 10% in volume in 2023, though they were up 4% in value. Mexico, our leading dairy export market, last year bucked the volume trend slightly, with the first 10 months of 2023 up 14% (165 million pounds) in volume but down 4% ($80 million) in value. Without foreign consumption of excess U.S. dairy supply, the resulting price received by farmers is pressured downward. This is especially true for certain dairy products, like cheese, where large cold stores loom.

Federal Milk Marketing Order Hearing

The ongoing Federal Milk Marketing Order hearing is set to reconvene on Jan. 16 in Carmel, Indiana. If the hearing is not completed by 5 p.m. ET, Jan. 19, the hearing will reconvene at 8 a.m. ET, Jan. 29, and will be held each weekday from 8 a.m. to 5 p.m. If the hearing is not completed by 5 p.m. ET, Feb. 2, it will be reconvened at a later date.

AFBF has taken a leading role in the hearing, supporting the return to the higher-of and raising the Class I differential, and advocating for the end of advanced Class I pricing, among other measures.

USDA categorized hearing topics numerically, with the failure of the “average-of” formula change part of category four. Remaining hearing discussions pertain to the final category on Class I and II differentials. With no certain end to the hearing, the outlook for when changes can occur stretches further. There are still many steps in the federal order hearing process before any referendum approved can be implemented. Remaining steps once the public hearing concludes include:

- USDA makes the hearing record available within two weeks of the end of the hearing.

- This includes publishing the transcript of everything that was said on the record during the hearing.

- Parties can file corrections to the transcript.

- Interested persons may file suggested corrections to the transcript of testimony by a date determined by the presiding official, not to exceed 30 days after the hearing record is made available.

- Participants file post-hearing briefs.

- Interested persons may file proposed findings and conclusions, and written arguments or briefs, by a date determined by the presiding official, not to exceed 60 days after completion of the hearing.

- USDA issues a recommended decision in the Federal Register.

- A recommended decision or, when applicable, a tentative final decision, will be released no later than 90 days after the deadline for submission of post-hearing briefs.

- Parties file comments and exceptions to the recommended decision.

- Comments and exceptions to a recommended decision may be filed with the USDA hearing clerk not later than 60 days after publication of the recommended decision in the Federal Register, unless otherwise specified in that decision.

- USDA issues a final decision.

- USDA shall issue a final decision not later than 60 days after the deadline for submission of comments and exceptions to the recommended decision.

- USDA holds a referendum and implements the amendments.

- Through a referendum process, producers are able to approve the federal order(s) as amended, or reject the proposed changes, effectively terminating the federal order(s). If approved by producers, the amendment(s) to the order(s) is published in the Federal Register as a final rule. The publication of the final rule announces when the amendment(s) become effective and concludes the rulemaking process.

- To modify a Federal Milk Marketing Order, at least a two-thirds majority of the eligible producers voting in the referendum, or the eligible producers who supply more than two-thirds of the milk represented in the referendum, must vote in favor of the order as amended. Cooperatives can currently bloc vote on behalf of their members.

Combined, the remaining steps include up to 270 days between when the hearing transcript is published and when a referendum may occur. This puts any likelihood of pricing regulatory changes into 2025 or later. It is important to reiterate if farmers reject the final rule in a failed vote, USDA has a precedent of terminating the order completely. This means instead of returning to the order regulations that were in place before the hearing, the order and its regulations cease to exist altogether. Additionally, any language passed in a future farm bill related to FMMO pricing regulations supersede the hearing process (i.e., if a switch back to the “higher-of” was included in a farm bill).

Conclusion

The monotonous process of amending federal orders, though important, means dairy farmers remain stuck with current pricing regulations until USDA publishes a final rule, that rule is approved by dairy farmers in a referendum and the stipulations around the timing and implementation of the rule are published in the Federal Register. In a market based on dynamics of transporting a highly perishable fluid product to processors, retailers and ultimately customers, even short spans of time result in wide pricing spreads and corresponding positive or negative impacts on producers. Current market dynamics underscore the need for FMMO modernization. The ongoing impacts of the Class I mover change are a prime example of a well-intentioned policy misstep that has reduced dairy farmers’ checks, with little relief in sight. An effective hearing outcome and comprehensive updated farm bill can buffer against mistaken and outdated policies that have left dairy farmers struggling to make ends meet.

Top Issues

VIEW ALL