Farmers’ Use of Paycheck Protection Loan Depends on ‘Small Business’ Definition

TOPICS

SBA

photo credit: Mark Stebnicki, North Carolina Farm Bureau

Veronica Nigh

Former AFBF Economist

Update, April 3, 2020. After the release and analyzation of the interim final rule for the Paycheck Protection Program, released on the evening of April 2, this article has been updated. Please find the updated story here.

*************

Last week we released a Market Intel, What’s in the CARES Act for Food and Agriculture, outlining the provisions of the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, Economic Security Act specifically intended for agriculture. This Market Intel delves into provisions of the CARES Act that, depending on how some provisions are interpreted by the Small Business Administration, could potentially provide a lifeline for ag producers. There are three main SBA programs that are of the most interest to agricultural producers: The Paycheck Protection Program Loan (PPPL), Economic Injury Disaster Loan (EIDL) and the Emergency EIDL grants.

Signed into law on March 27, the CARES Act provides more than $2 trillion in economic stimulus. It also launched a host of questions about how quickly government agencies could write the rules for the programs included in the legislation. A significant amount of that stimulus was directed toward the SBA, which will oversee $350 billion in dedicated funding to prevent layoffs and business closures while workers have to stay home during the COVID-19 outbreak. SBA has been working feverishly to provide guidance on these programs, but understandably, we’re still awaiting many important details. We know the most about the Paycheck Protection Program Forgivable Loans, which will be the focus of this article. Once additional details are released about the other programs and how they treat production agriculture, we will follow up with Market Intel articles.

Paycheck Protection Program Loans (PPPL)

Tuesday, the SBA and the Treasury Department announced that they have initiated a robust mobilization effort of the PPPL. In a nutshell, the PPPL is designed to help small businesses keep their employees paid through this difficult period. The PPPL provides $349 billion in forgivable loans to small businesses to pay employees and keep them on the payroll. These loans are open to most businesses under 500 employees, including non-profits, the self-employed, startups and cooperatives. While agricultural producers are eligible for the PPPL, it may be less useful to them than originally hoped.

The PPPL will provide eligible businesses loans of up to $10 million to cover 2.5 times the average monthly payroll costs, measured over the 12 months preceding the loan origination date, plus an additional 25% for non-payroll costs. Payroll costs include salaries, commissions and tips; employee benefits (including health insurance premiums and retirement benefits); state and local taxes; and compensation to sole proprietors or independent contractors. Non-payroll costs include interest on mortgage obligations incurred before Feb. 15, 2020, rent under lease agreements in force before Feb. 15, 2020, and utilities for which service began before Feb. 15, 2020.

The real highlight of the PPPL however, is that the portion of the loan that covers eligible expenses within an eight-week period from Feb. 15, 2020 – June 30, 2020, is forgivable, as long as the company maintains staff and payroll. Any loan proceeds in excess of this amount are subject to repayment at a rate of 0.5%. The maximum duration of the PPPL loans is two years.

Certainly, for those businesses that qualify, the PPPL will be a significant help. However, there are a few provisions that could make it difficult for agricultural producers to use, depending on how those provisions are interpreted. The first potentially limiting factor for farmers is that payroll expenses cannot include salaries for foreign workers or independent contractors. According to the Department of Labor’s National Agricultural Workers Survey of U.S. crop workers, only 50% of workers were U.S. citizens or legal permanent residents, making 50% of crop workers ineligible for this program. This exclusion will be particularly limiting to fruit, vegetable and nut producers and the dairy sector, all heavily reliant on foreign labor. In addition, many farm business owners rely heavily on independent contractors, also sometimes referred to as 1099 workers. Under the PPPL, farm businesses should not include 1099 payments when calculating their average monthly payroll for the purposes of getting a loan. The thinking here is that 1099 workers can apply for PPP loans on their own, so business owners shouldn't be counting those payments as payroll.

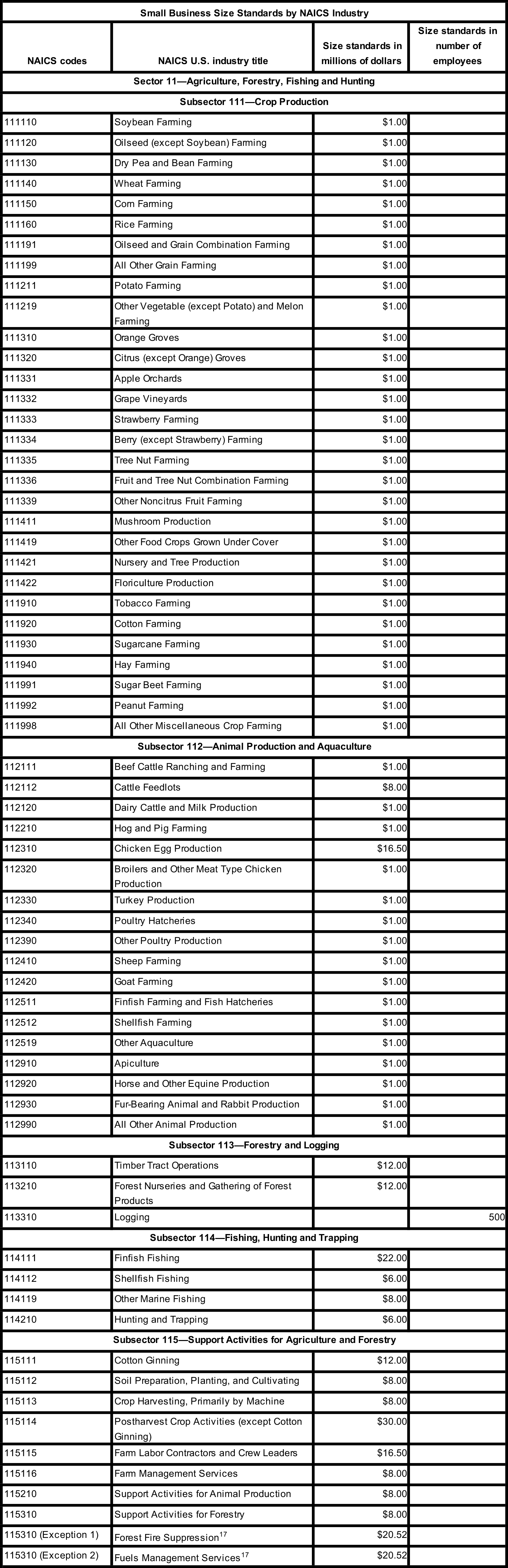

The other provision of concern relates to size limitations. While the headline eligibility defines a small business as one having 500 employees or fewer, the PPPL also stipulates that a small business must meets the SBA small business industry-specific standards. The industry-specific standards are set using the North American Industry Classification System, which is a classification of business establishments by type of economic activity. Under the industry-specific standards, a small business classification is based on either the number of employees or annual receipts in millions of dollars, but not both.

For example, by the industry-specific standards, a crude petroleum extraction business can have 1,250 employees and still be considered small. Meanwhile, a steam and air-conditioning supply business is considered small if its annual receipts are below $16.5 million. Some are interpreting Congress’ intention with the CARES Act to mean that the industry-specific threshold applies to the number of employees only, not the receipts. This interpretation would make it so that the crude petroleum extraction business of 1,250 is still considered small, even though it is above the 500 employees or fewer headline eligibility. Another interpretation is that the industry-specific number of employees and the annual receipts are both applicable in determining eligibility. Which interpretation wins the day will determine how helpful this program is for agricultural producers.

Agriculture, forestry, fishing and hunting are divided into various subsectors, which each have subsectors of their own, drilling all the way down to production level. For most of the agriculture NAICS codes, the definition of small is based on annual receipts, not the number of employees. It is worth noting that though other areas of SBA eligibility were expanded in the CARES Act, the industry-specific standards were not. The full table of those size standards is included below, but a good example of this limitation lies in the crop farming subsector. In this subsector, the maximum level of receipts (not profits) that a strawberry farm can have and still be considered small is $1 million. To put give context to how limiting this is: In 2017 the average strawberry yield per acre was 50,500 pounds and the average grower price for fresh strawberries was $125/hundredweight. This means the average revenue (again not profit) was about $63,125 per acre. At this rate, a strawberry farm of 16 acres would exceed the $1 million threshold for a small business. This is just one example of how limiting the SBA industry-specific standards are for agriculture.

Conclusion

Intended to keep small business employees on the payroll, the PPPL will likely be an important lifeline for many, including independent contractors and the self-employed who will benefit from the program’s expanded eligibility. However, if the SBA interpretation of the CARES Act is that the industry-specific number of employees and annual receipts, without any expansion, are both applicable in determining eligibility, most of production agriculture will be on the outside looking in on the benefits of this particular program.

**********

Update, April 3, 2020. After the release and analyzation of the interim final rule for the Paycheck Protection Program, released on the evening of April 2, this article has been updated. Please find the updated story here.

Trending Topics

VIEW ALL