Farmers and Ranchers Feel Crunch of Railway Supply Chain Shortfalls

TOPICS

Transportation

photo credit: Getty Images

Daniel Munch

Economist

The domestic rail transportation network is vital to the movement of products and goods supplied by America’s farmers and ranchers. U.S. railways account for nearly 28% of freight movement, second only to trucks within the domestic transportation system. Over the past two years, starting with the COVID-19 pandemic and exacerbated by global geopolitical rifts, supply chain efficiency has plummeted, with heavy disruptions across freight delivery. In a previous Market Intel, Increasing Freight Rail Rates Put Additional Pressure on Farm and Ranch Income, we outlined some of the factors complicating farmers’ and ranchers’ ability to cost-effectively utilize rail systems to move their products. Today, with growing reports of reduced delivery service, we provide an agriculture-focused status update on U.S. rail networks.

Some quick background: U.S. freight railroads are privately owned. As independent businesses they are responsible for the maintenance and efficiency of their railways, as well as for setting competitive rates (generally called "tariffs” by the rail industry) and formulating contracts. Approximately 94% of the revenue generated by the rail system belongs to seven Class I railroad-operating firms. Class I rail firms are defined as having inflation-adjusted annual carrier operating revenue of $900 million or more and include Burlington Northern and Santa Fe Railway (BNSF), Canadian National Railway (CN), Canadian Pacific Railway (CP), CSX Transportation, Kansas City Southern Railway (KCS), Norfolk Southern Railway (NS) and Union Pacific Railroad (UP).

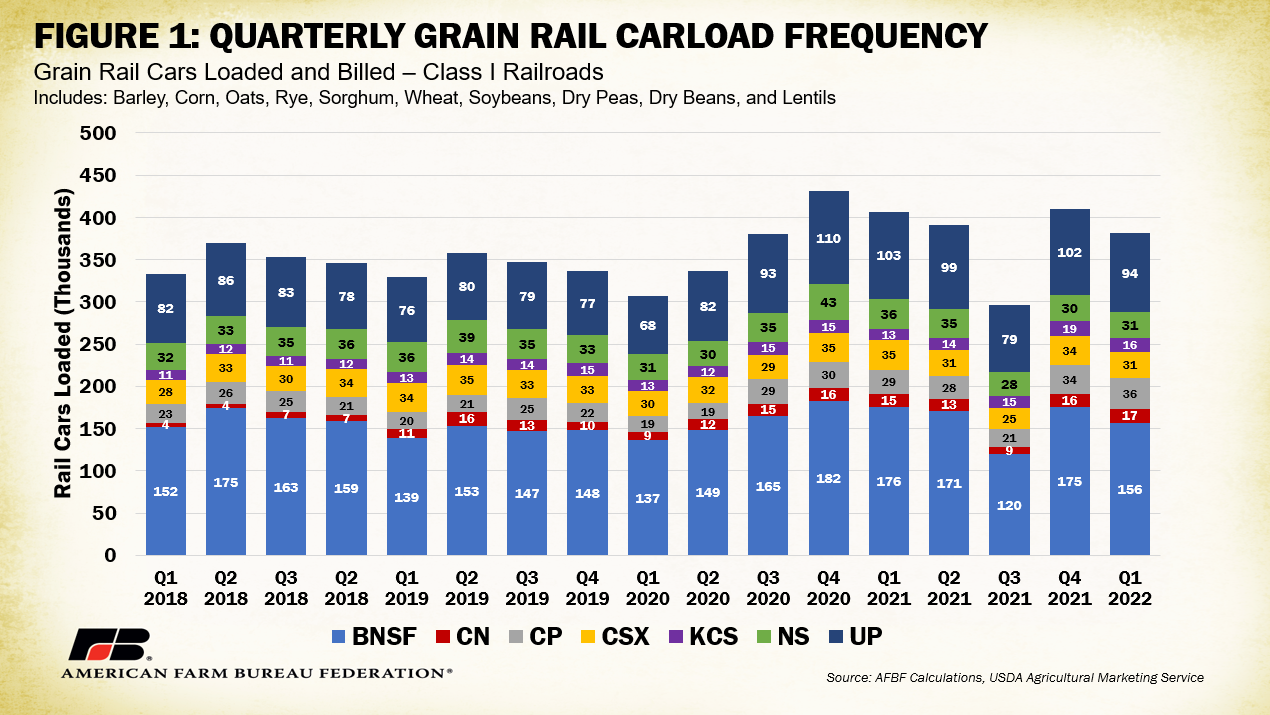

Looking at how frequently grain rail cars are loaded and billed, as of the first quarter of 2022 there is still no obvious upward trend that would signify an abnormal increase in demand pressuring rail systems. The number of grain cars loaded and billed by Class I railways in the first three months of the year was about 25,000 units below the first quarter of 2021 and 75,000 and 50,000 units above the first quarters of 2020 and 2019, respectively. This range is well within the average variation between quarters and suggests grain car movements are not unusually high or low, so far, in 2022. Figure 1 displays these quarterly frequencies by railway. You will notice the proportion of cars loaded and billed by each railway firm remained relatively stable over the period analyzed, with BNSF and UP claiming approximately 70% of the total. Given railways exist in specific, generally immovable locations, if railroads that control a large portion of grain movements experience service disruptions, a correspondingly large portion of shippers and product delivery will be impacted since those routes cannot be easily shifted.

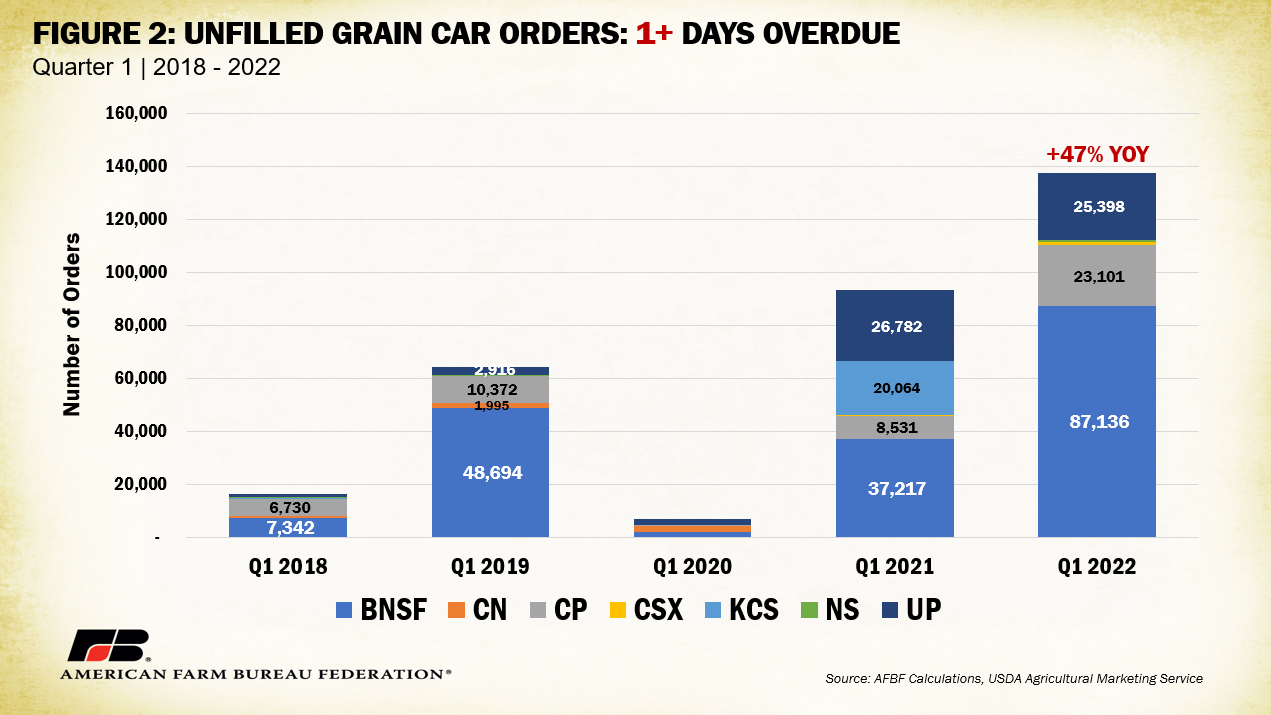

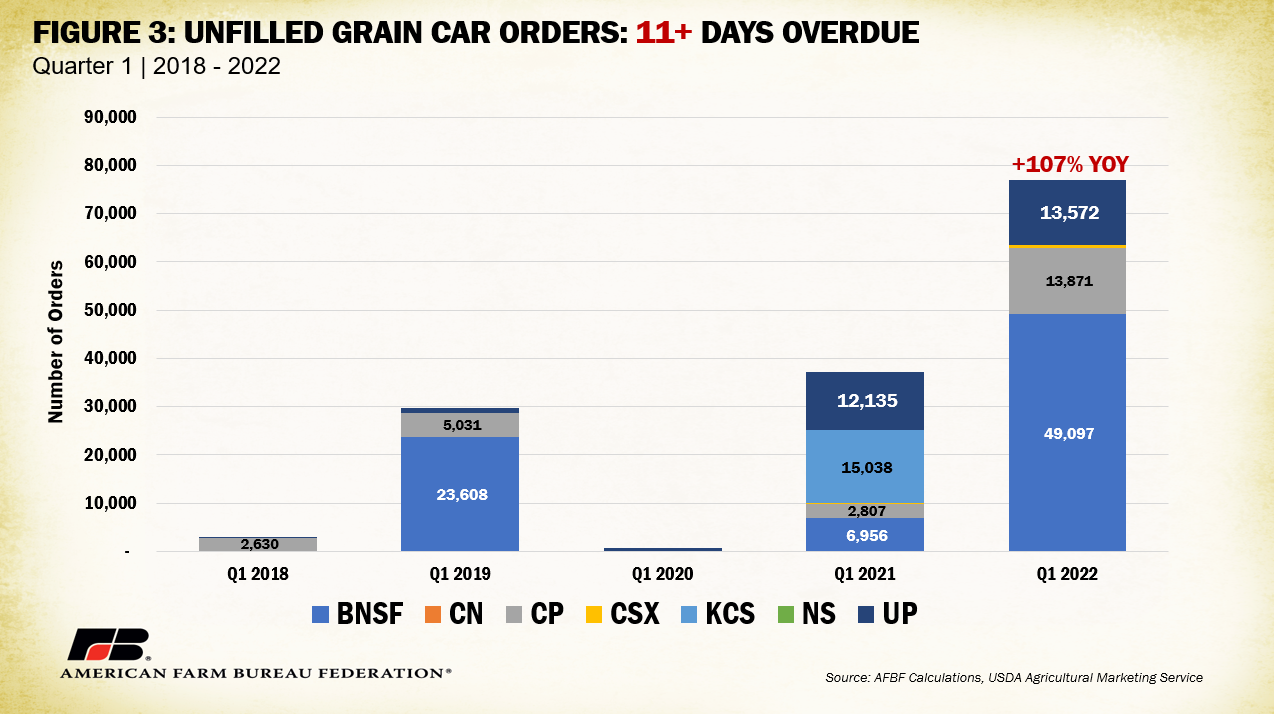

One metric that can better reveal rail service disruptions and how fluidly grain cars are moving through the rail network is the number of unfilled grain car orders. Each railroad reports their definition of “unfilled order” slightly differently but generally it is the number of cars a shipper (such as a grain elevator) ordered but did not receive. For example, if a grain elevator ordered 10 cars from a railroad and received seven, that would leave three unfilled orders. Though railroad companies report the number of these unfilled orders to the Surface Transportation Board weekly, the dataset does not distinguish between rail cars still undelivered between weeks or new undelivered grain cars. This means grain cars that are still undelivered over one week are counted again in the following week’s report until successful delivery. For example, in a quarter with 130,000 cumulative weekly unfilled grain car orders it is possible that 10,000 grain cars were undelivered consecutively over the 13 week period, 130,000 different grain cars went undelivered at one point within the 13 weeks, or a combination of the two. Regardless, this unit allows for an overtime comparison of reported unfilled orders in one statistic. Figure 2 displays the cumulative number of weekly grain car orders in the first quarter from 2018 to 2022 that were one or more days overdue. Between the first quarter of 2021 and the first quarter of 2022, the cumulative number of these unfilled orders jumped from 93,000 to 137,000, a 47% increase. By percentage increase, NS saw the largest jump (1,614%) followed by CP (171%) and BNSF (134%). By numerical increase, BNSF reported the largest jump – nearly 50,000 cumulative unfilled orders – followed by CP with an additional 14,500 cumulative unfilled orders. Figure 3 displays orders that are 11 or more days overdue. You will notice more than half of the orders one or more days overdue were also 11 or more days overdue, revealing the severity of disruption for some shippers. Between the first quarter of 2021 and the first quarter of 2022, the cumulative number of 11+ overdue orders jumped 39,000, or 107%. By percentage and numerical increase, BNSF saw the largest jump — 606% or 42,000 unfilled orders — followed by CP with 394% and 11,000 unfilled orders.

This cumulative unfilled order metric could explain why increased demand is not discernable in the grain carload frequency (Figure 1) measurement. Since reported frequency includes only cars loaded and billed, orders that lay outside the railroads’ ability to effectively deliver will be reflected in the unfilled metric. Even still, grain cars loaded and billed for the first quarter of 2022 were lower than the same period last year. When grain shippers are unable to receive orders from railroads it disrupts agriculture markets throughout the broader supply chain. Flour and feed mills waiting on deliveries of grain that never arrive could be forced to temporarily cease operating and cut off sales to customers until deliveries return. This means livestock operations that are reliant on the feed shipped from these mills may be forced to ration or stop feeding until deliveries return, or find alterative feed options, stunting the production cycle and putting the health and wellbeing of livestock at risk. At a minimum, increases in unfilled orders would shift some shippers from the primary railcar market for service contracts into the secondary rail market to attempt to make up for delayed orders.

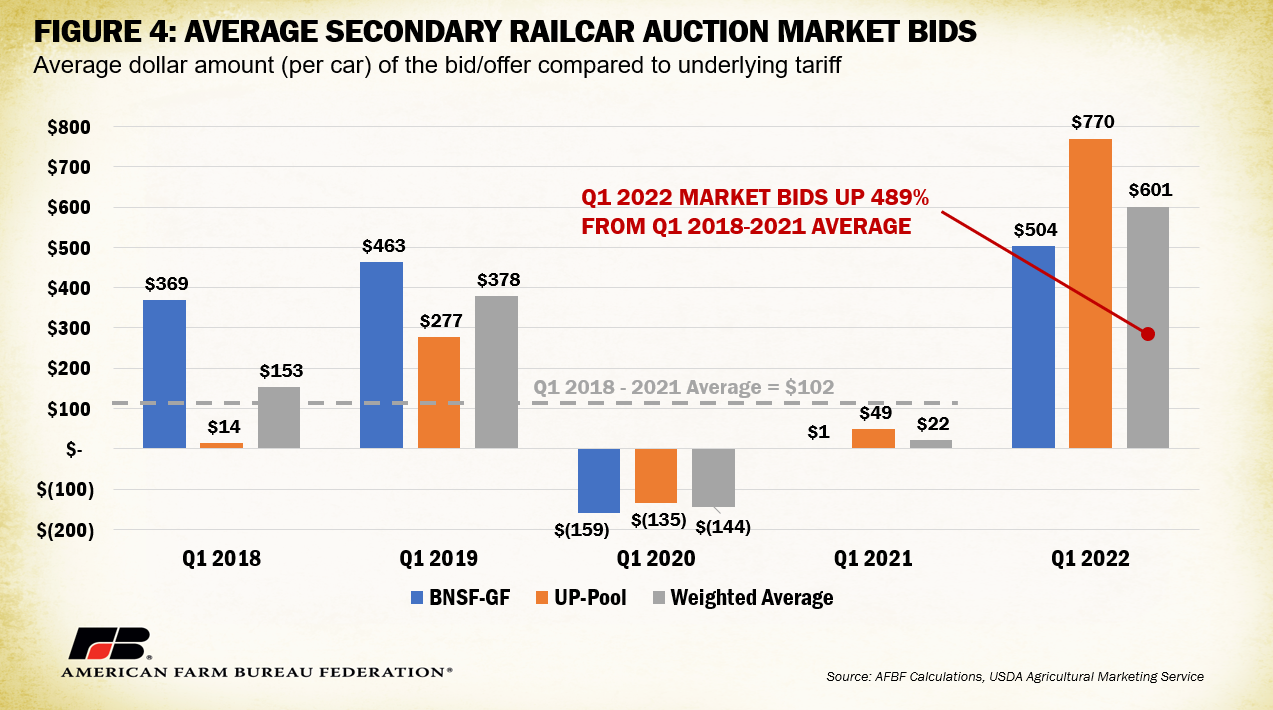

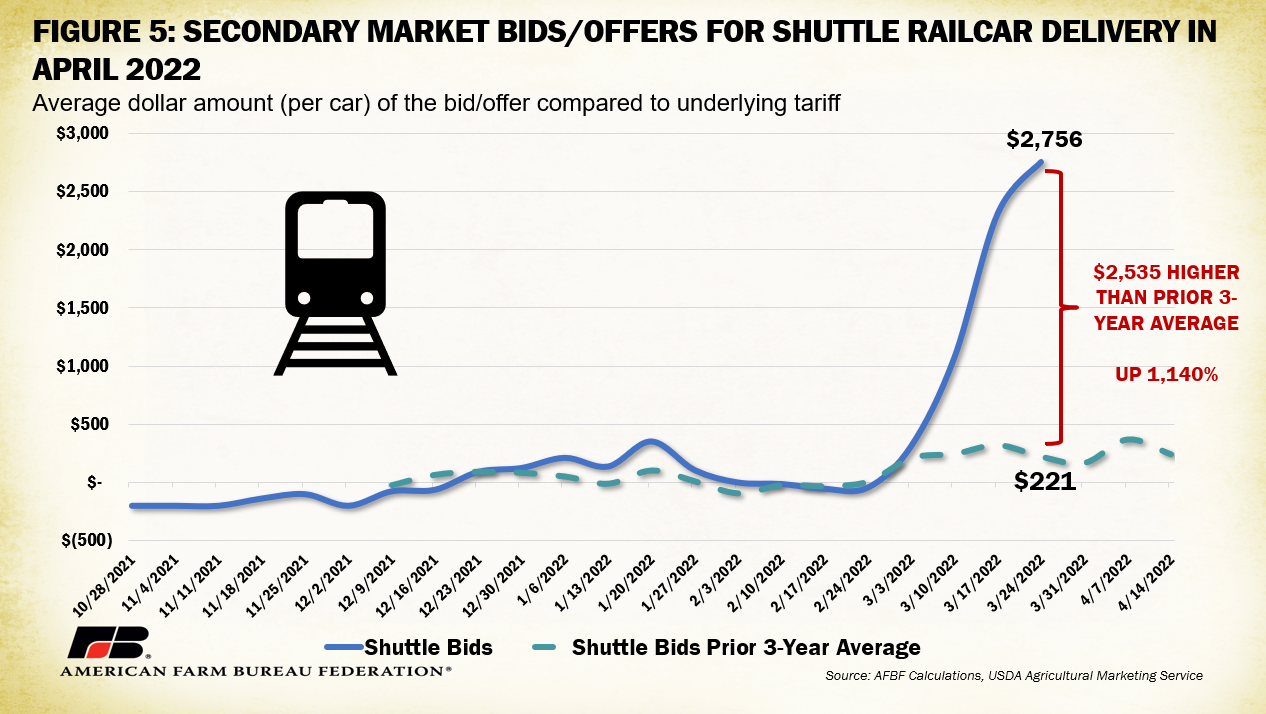

The primary rail market refers to when service contracts are first auctioned directly from railroads to shippers. Bids may be higher or lower depending on the demand for railcars but generally remain more in line with tariff rates published by the railway, which tend to reflect the most likely market conditions. For reference, average published per-car grain tariffs (including fuel surcharges) were $5,195 in the first quarter of 2021 and $5,378 in the first quarter of 2022, a 4% increase. This corresponds to an average $1.37 per bushel and $1.41 per bushel for the same periods, respectively. Railroads typically only change published rates once or twice per year and are required by law to give a 20-day notice prior to changing tariffs. This insulates buyers from short-term market changes resulting from unexpected events, like weather, or service disruptions. It does not, however, guarantee orders will be received because of these disruptions. In these cases, or in general cases when shippers who are looking to buy or sell a contract go directly to another shipper to receive or place bids, they are participating in the secondary rail market. Sales that occur in this secondary stage may either represent a premium or a discount to the underlying original tariff rate and are reported as a positive or negative value, respectively. When disruptions in rail service increase, shippers will likely look to the secondary market for another chance to get orders filled. Thus, high demand for cars in this market pushes rates up far above the original underlying tariff.

Figure 4 shows the average dollar amount per bid above or below the original primary market service contract value for the first quarter between 2018 and 2022. Comparing the weighted average data point (between BNSF and UP) for the first quarters of 2018-2021 to the first quarter of 2022 shows a near 500% increase in secondary railcar grain auction bids (from $102 to $602). The premium cost shippers are willing to pay in the secondary market helps illustrate the severe magnitude of demand for grain rail contracts so far in 2022.

Similarly, bids in the secondary market for shuttle service have escalated significantly in the past several weeks. USDA defines a shuttle train as having more than 75 cars that originate at a single origin and go to a single destination (for instance a grain elevator to rail yard). As shown in Figure 5, for the week ending March 24, bids/offers were over $2,500 higher than the prior three-year average for shuttle railcars to be delivered in April, an 11-fold increase. Both secondary market metrics signify how service disruptions in existing contracts force shippers to enter the secondary market and attempt to obtain different contracts to get orders delivered, albeit at a super-inflated rate.

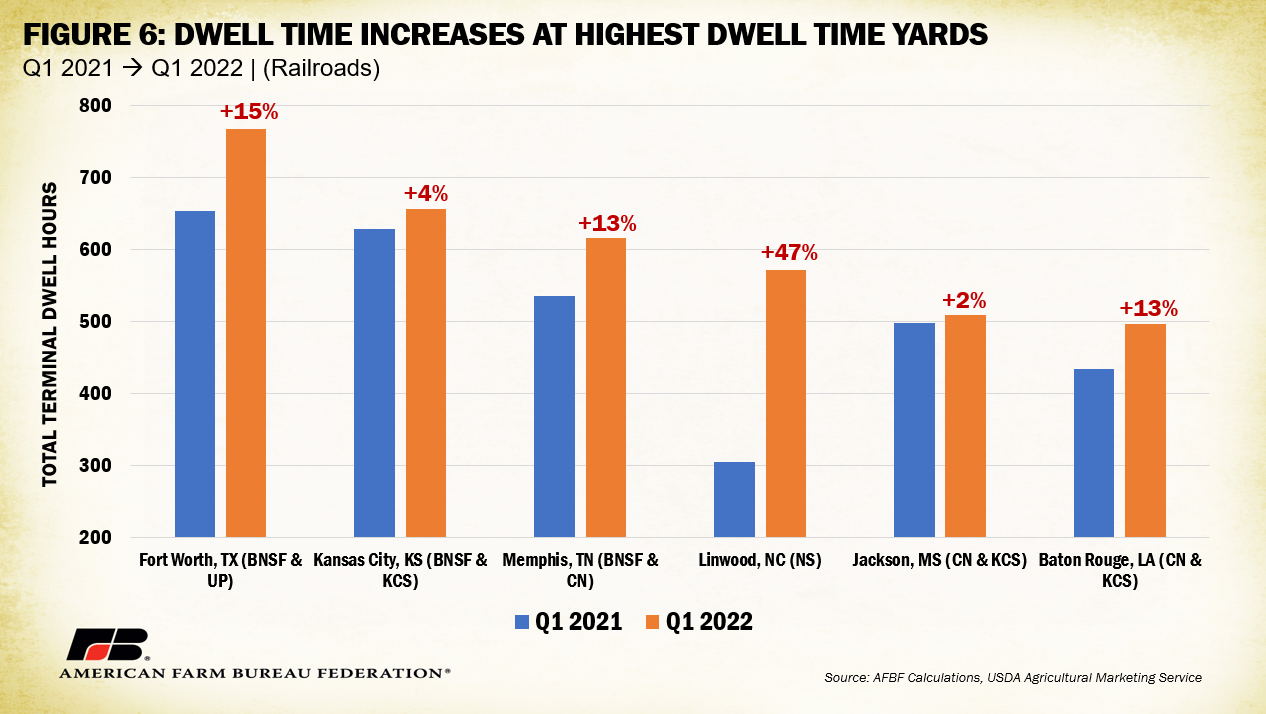

Other metrics are also available to measure service quality on railways. Rail speeds, or the average speed of trains (in miles per hour), can shed light on the fluidity of a rail network. Overall, compared to the first quarter of 2021, train speeds in the first quarter of 2022 were down 5%. Considering train speeds of grain cars by railroad during the same timeframe, NS had a 20% drop in average train speed (over 3.5 mph), followed by KCS and CN, which both dropped 8%. Rail origin dwell times, the number of hours trains spend waiting after initial release at origin, have increased by 9% across railroads between the first quarter of 2021 and the first quarter of 2022. They are the highest for CSX (+73%), BNSF (+28%), UP (+26%) and NS (+20%). On the terminal dwell time side, increases at some of the busiest rail yards in the country are common. Figure 6 shows the top six rail yards in terms of average terminal dwell time and the total number of dwell hours in the first quarter of 2021 versus the first quarter of 2022, with their corresponding railroad carrier(s) listed in parenthesis.

Reasons for service and quality disruptions on railways can vary widely. Labor and crew availability remains a major hurdle across all segments of the transportation system and worker shortages within railways can lead to delays, held trains and general service disruptions. Weather and mechanical issues can slow or stop operations. Delays make it more difficult for orders to be filled down the line. Cars bound for future orders get tied up in the delay, forcing the railway to either figure out how to reduce congestion or add more railcars into service. Car inventory is an additional hurdle. If there are not enough cars to cover additional orders, delays will compound. Railroads may have made COVID-19-related decisions to liquidate assets, such as railcars, and are now left with gaps in their ability to fill orders. Intermodal containers, or shipping containers used across multiple modes of transportation like ocean barge to railway or truck, have been impacted by global market issues. A new round of COVID-related shutdowns across China has halted movement of around 10% of the global container-ship fleet and with it, a significant portion of containers. Containers held up oversees can limit order movement domestically and put pressure on other car and container types used by agricultural buyers. Manufacturing disruptions and delays for new locomotives and containers also shorten capacity to pick up additional orders. All of these factors heighten obstacles railway customers, like farmers and ranchers, face in marketing their products.

Conclusion

Railways are a vital piece of the supply chain and are usually a cost-effective and reliable way to get agricultural goods to their destination. Current rail service disruptions associated with labor shortages, railcar inventory and capacity, weather and shortfalls in other global transportation networks have contributed to a large increase in the number of unfilled orders faced by shippers. Unfilled and delayed orders mean a disruption in the general delivery of agricultural and other goods to buyers. For example, milling operations reliant on just-in-time delivery of grain from elevators are forced to halt operation, putting the essential flow of feed to livestock operations at risk. Shippers scrambling to find alternative methods to deliver their goods are seeing steep, multifold increases in the price to acquire service contracts in the secondary railcar market. Competing transportation options, like trucking, have their own slew of service shocks and remain a far costlier, often less efficient option.

Speaking of costs, farmers paying for storage in grain elevators that cannot move product may face added holding fees, contributing to even higher marketing expenses. In addition, service disruptions impact local basis for cash commodities that influence the price farmers receive for their crops. News of possible rail-related mergers or line closures also reveal concerns about the impacts of consolidation in the railway market and amplify questions of how competitive forces will be maintained. Altogether, a handicapped railway system puts the profitability of many farms, ranches and agribusinesses at risk and contributes to uncertainty in already unsettled commodity markets. Beyond creative solutions to immediately improve railway efficiency, long-term investments in on-farm and on-operation storage facilities may help hedge against transportation disruptions. In any case, improvements will need to be in place soon to prevent further disruptions in across the farm economy.

BNSF recently acknowledged that service is not where it needs to be and shared specific details of a service restoration plan already in process focused on crew and locomotive availability as well as car inventory management.

Trending Topics

VIEW ALL