Farm Bankruptcies During 2020

TOPICS

Farm Economy

photo credit: Mark Stebnicki, North Carolina Farm Bureau

John Newton, Ph.D.

Former AFBF Economist

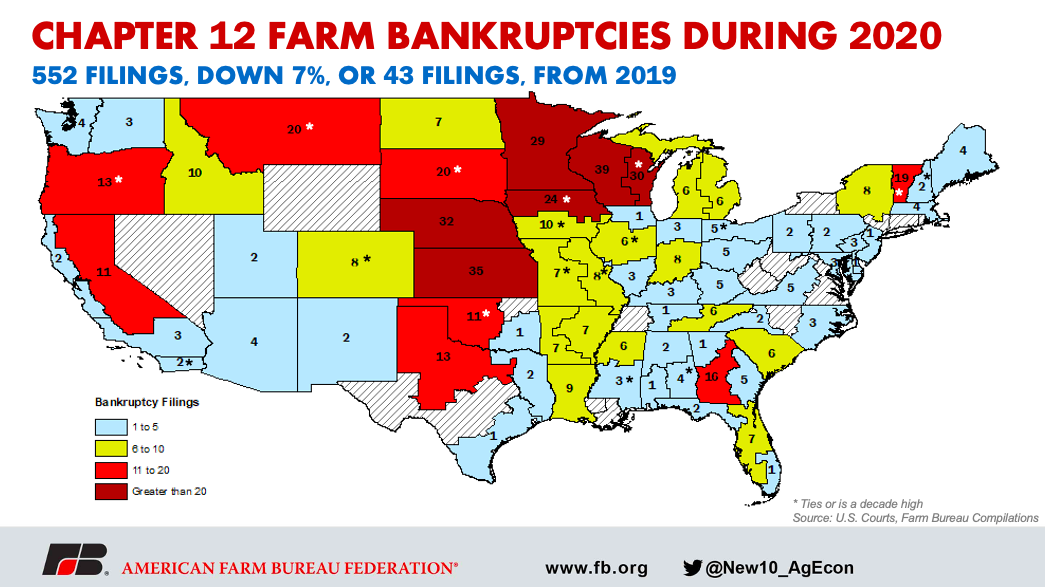

Recent higher commodity prices and ongoing ad hoc financial support to offset natural disasters, retaliatory tariffs and coronavirus-related damages have come a little too late for some farmers across the U.S., i.e., 2020 Farm Profitability: A False Positive. The impact of multiple years of low commodity prices and delayed distribution of disaster assistance relief, followed by a global pandemic is visible in recently released caseload statistics from the U.S. Courts, which indicate that Chapter 12 family farm and family fishery bankruptcies totaled 552 filings during 2020, down 43 filings, or 7%, from 2019, but also the third highest over the last decade.

Bankruptcies by District Court

Data at the District Court level indicates that Chapter 12 bankruptcies were the highest in western Wisconsin at 39 filings, followed by Kansas at 35 filings, Nebraska at 32 filings and eastern Wisconsin at 30 filings. The 10 District Courts with the highest number of filings represented 48% of all Chapter 12 bankruptcies during 2020. In 17 districts the number of Chapter 12 farm bankruptcies tied with or reached decade-high levels. These areas include but are not limited to eastern Wisconsin, Iowa, South Dakota, Montana and Vermont. Many of these areas have been hard hit by multiple years of low commodity prices, e.g., corn, soybeans, wheat and cotton, lower yields and low milk and livestock prices.

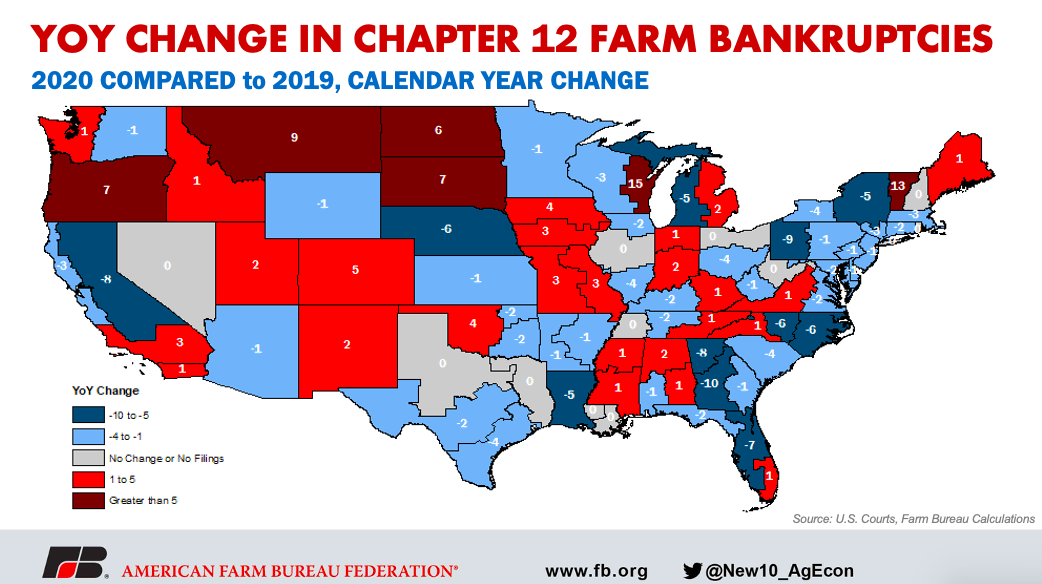

In 33 of the 94 districts, Chapter 12 bankruptcies increased from prior years. The increase in Chapter 12 filings was the highest in eastern Wisconsin at 15 filings, followed by Vermont at 13 filings. In 44 districts the number of Chapter 12 filings decreased relative to previous years. The decrease was the largest in middle Georgia, which had 10 fewer filings, and western Pennsylvania, which had nine fewer filings.

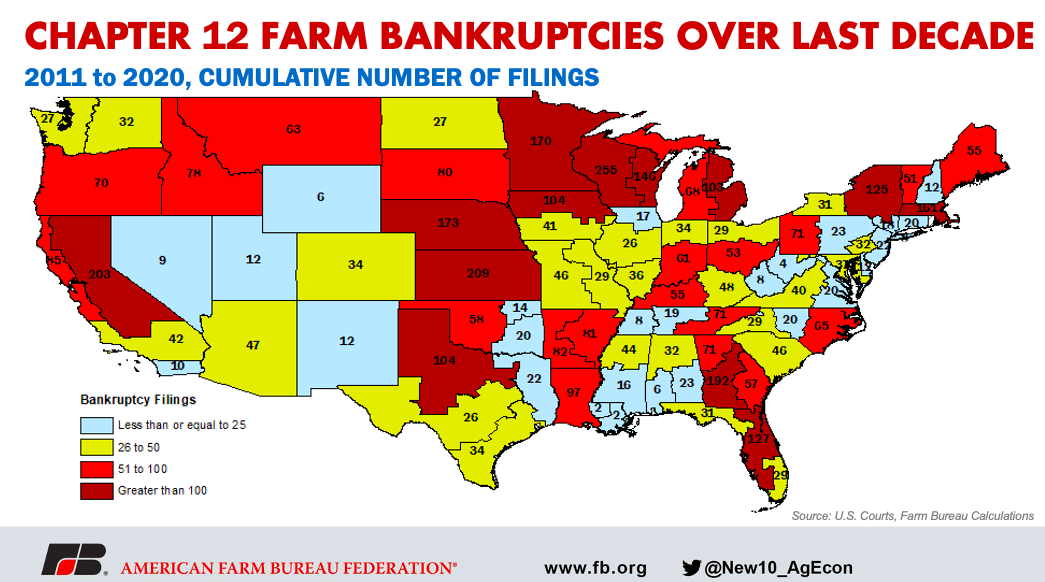

Over the last decade, there have been nearly 5,000 farm bankruptcies – less than a quarter-percent of all farm operations in the U.S. Based on a survey conducted by the Association of Chapter 12 Trustees, more than half of these filings were likely to complete a Chapter 12 reorganization or negotiate a mutually acceptable outcome, which may result in a dismissal of the case or conversion to Chapter 7 (Farm Bankruptcies Slow, More Aid Needed).

Total filings over the last decade were the highest in western Wisconsin at 255 filings, followed by Puerto Rico (not pictured) at 214 filings, Kansas at 209 filings, eastern California at 203 filings and middle Georgia at 192 filings. The 10 districts with the highest number of filings had 1,850 filings over the last decade, approximately 38% of the national total.

Summary

Over the last few years, many farmers have experienced low commodity prices, high production costs, increasing agricultural land values, increasing cash rents, increasing labor costs, and high capital barriers to entry, among other problems. Off-farm income, which many farmers rely on, has also been a challenge given COVID-19 restrictions and inadequate broadband access. For many highly leveraged farmers, including new and beginning farmers, low commodity prices and high input costs could not be sustained.

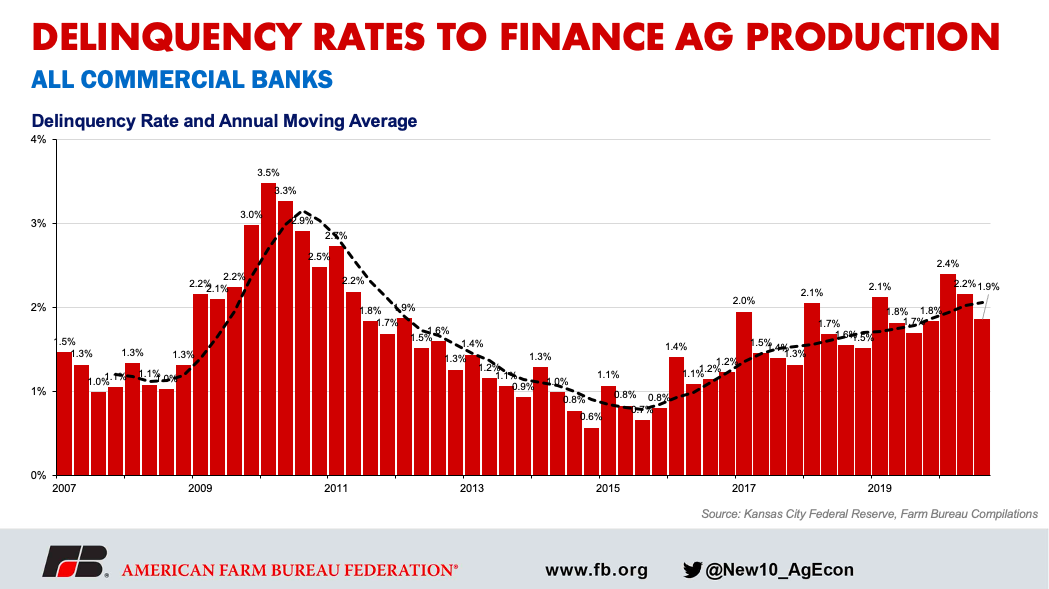

According to the Kansas City Federal Reserve, delinquency rates at commercial banks continue to increase, and USDA recently temporarily suspended debt collections, foreclosures and other activities on farm loans to support distressed farmer borrowers. According to USDA, more than 12,000 farmer borrowers will benefit from these recently announced debt suspension plans.

While Chapter 12 bankruptcies have declined compared to year-ago levels, these numbers should not be considered a sign that the farm economy has recovered. Additionally, given the difficulty of working remotely during the pandemic, the decline in bankruptcies, which can only be filed online at this time, may not fully reflect on-farm economic conditions. For example, there were more than 230,000 fewer bankruptcy filings in 2020 compared to 2019 (774,940 filings in 2019, compared to 544,463 filings in 2020). Moreover, since bankruptcy debtors remain unable to access Paycheck Protection Program loans, some small agricultural businesses may be delaying their bankruptcy filing in the hopes of qualifying for the PPP.

Chapter 12 bankruptcy is often the last option for agricultural producers, as many have likely already taken steps with their lenders to reduce their operating costs, liquidate assets or transition their operation to avoid bankruptcy. Put simply, a single year of favorable farm income is unlikely to reverse a farm’s multi-year journey toward bankruptcy.

USDA’s first Farm Income Forecast for 2021 will be released on Feb. 5. While many expect cash receipts from the sales of crops and livestock to increase, some expenses are likely to increase and ad hoc federal support will certainly be lower. The net effect will likely be lower, but above average, net farm income in 2021.

Key to turning the farm economy around is a COVID-19 recovery, restored demand for biofuels, increased U.S. agricultural trade and new sources of income, such as those from adopting climate-smart practices and ecosystem services markets.

Trending Topics

VIEW ALL