Ethanol Exports and RIN Generation

TOPICS

Transportation

photo credit: Arkansas Farm Bureau, used with permission.

John Newton, Ph.D.

Former AFBF Economist

A recent Market Intel article, Stop the RIN-sanity, reviewed proposed modifications to the Renewable Fuel Standard, including year-round sales of higher blends of ethanol, a cap on the prices of Renewable Identification Numbers and allowing exported ethanol and other biofuels to generate RINs. In early May the White House met with key senators and ethanol and fuel industry stakeholders to make a deal on modifications to the RFS.

What’s in the Deal?

On May 8, 2018, the White House acknowledged an agreement in principle on several modifications to the RFS designed to lower the price of RINs. These modifications do not include a cap on RIN prices. Instead, they would allow year-round sales of E-15 -- transportation fuel with a 15 percent ethanol concentration -- and then would allow RINs to be attached to domestically produced ethanol and biofuels that are exported. The RINs associated with the exported ethanol could then be used to meet annual volume obligations.

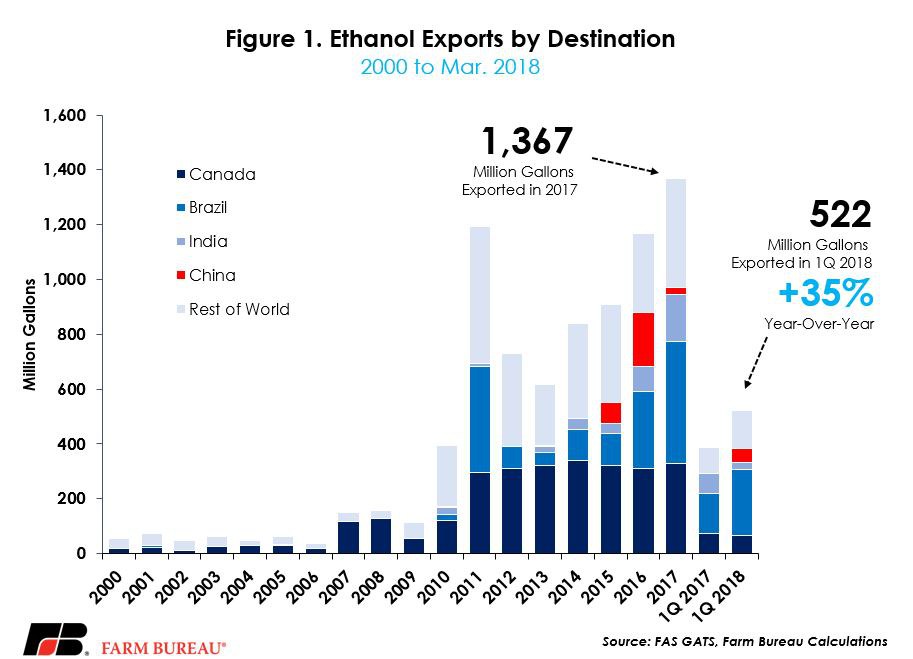

During 2017, the U.S. exported a record-high 1.4 billion gallons of ethanol, 17 percent higher than exports in 2016. The top markets for U.S.-produced ethanol in 2017 included Brazil, Canada and India. During the first quarter of 2018, ethanol exports have increased 35 percent over prior-year levels, to 522 million gallons, Figure 1.

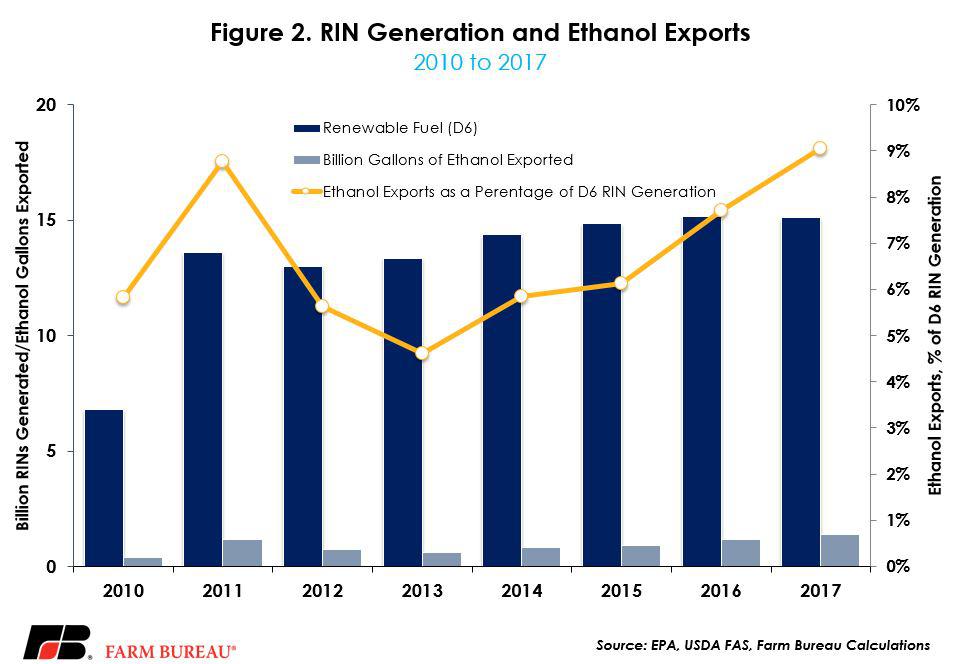

Renewable fuel RIN generation in 2017 totaled 15.1 billion RINs. Figure 2 highlights RIN generation, ethanol exports and ethanol exports as a percentage of RIN generation. As evidenced in Figure 2, and assuming each gallon of ethanol exported would generate one RIN, RINs generated on ethanol exports, not including biofuel exports, could increase renewable fuel RIN supplies by 5 to 10 percent.

Larger RIN supplies are likely to lower the price of RINs and would erode the integrity of the RFS program by weakening the principal RFS compliance instrument. Additionally, the ability to generate ethanol RINs upon export – without incurring the processing costs associated with blending -- could reduce the incentive to blend higher concentrations of ethanol-containing transportation fuel. As a result, while year-round E-15 would be permitted, there may be little to no incentive to actually blend higher grades.

Uncertainty Remains

Certainly, challenges remain on this issue. First, a recent farmdoc daily article, Deal-Making on the RFS: Follow the North Star, suggested that exported ethanol counted toward the annual volume requirements could violate the RFS statute as these exports are not domestically consumed in the U.S. transportation fuel supply. Finished gasoline gallons that are exported do not count towards refiners’ obligations under the RFS for this very reason.

Second, by generating a RIN, exported ethanol has an additional financial value that is equal to the value of the RIN. If the financial value of the RIN is not captured by the importer but instead is held by the exporter, this could effectively be viewed as an export subsidy on ethanol. Such a scenario could potentially raise the ire of the World Trade Organization – or result in retaliatory tariffs. Regardless, customers abroad will know the value of the RIN is there for the exporter and as a result will have a lower willingness to pay for U.S.-produced ethanol.

Significant resistance remains in the biofuels and agricultural sectors due to the economic harm and trade-distorting impact of the RIN-for-export proposal. While farmers and ranchers praise the potential for higher blends of ethanol in the fuel supply, the stick attached to that carrot would undermine the RFS and weaken ethanol demand at a time when farm income is at 12-year lows and farm bankruptcies are climbing. Due to these economic and legal uncertainties, a final agreement on modifications to the RFS as it pertains to ethanol exports and RIN generation is unlikely to be finalized any time soon.

Trending Topics

VIEW ALL