EPA’s Small Refinery Waiver Proposal Is an Unbalanced Approach for Agriculture

TOPICS

USDAMichael Nepveux

Economist

photo credit: Right Eye Digital, Used with Permission

Michael Nepveux

Economist

Introduction

Less than two weeks after the Trump administration’s well-received promise to address the devastating impact small refinery exemption waivers were having on renewable fuel demand, EPA on Oct. 15 released a supplemental notice of proposed rulemaking for the Renewable Fuel Standard program, which received a much icier response.

EPA’s initial statement, in which Administrator Wheeler said farmers could count on the 15-billion-gallon ethanol requirement for 2020 under the RFS statute, was somewhat vague, but still widely interpreted by the biofuel and agriculture industries as a step in the right direction. A week and a half later, many of the same groups that had applauded the administration’s RFS efforts were expressing consternation at the agency’s actual proposed plan.

What in the details ultimately frustrated the industry and what was changed from the earlier announcement that caused the biofuel and agriculture industries to turn their back on the proposed rule? The consensus among the industry is this plan did not reflect the original announcement to project SREs in future years by using a three-year average of past SRE allocations, and instead proposed weighting SREs by partial exemption recommendations made by Department of Energy scores – ultimately likely to reduce SRE projections and undermine the compromise between the biofuel and crude oil sectors weeks ago. This recent proposal falls short of EPA’s initial announcement by not adequately addressing the harm caused by the SREs, and it is understandable that so many are frustrated by what now appears to be a bait and switch.

SRE background

The U.S. Renewable Fuel Standard includes a provision to temporarily exempt small refineries from their renewable fuel volume obligations. A small refinery is defined as having an average crude oil input of less than 75,000 barrels per day. Refiners submit a petition for exemption to EPA. The agency may grant the permit only if, using evidence provided in the petition for exemption, it determines that “disproportionate economic hardship” exists for the refinery in that year. Congress provided all small refineries with a temporary exemption from the RFS from 2007 through 2010, and that exemption was later extended by two years in connection with a DOE study on the issue.

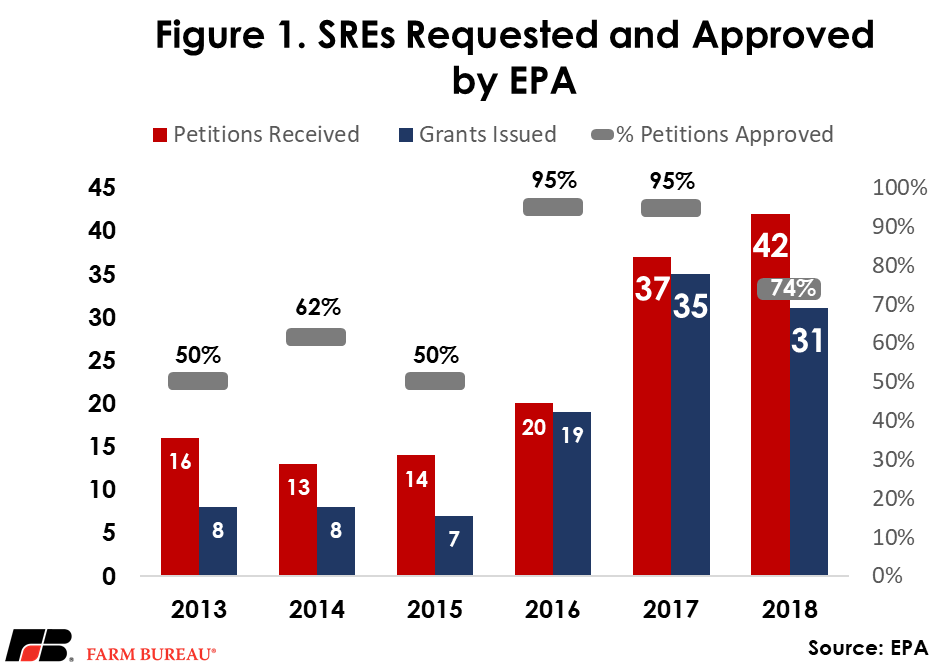

From 2013 to 2015, between 13 and 16 SRE petitions were submitted annually, while EPA accepted seven or eight of those petitions. Under former EPA Administrator Scott Pruitt, we began to see an increase in the number of SREs requested and approved. EPA retroactively granted a large number of exemptions for the 2016 compliance year, bringing the total grants issued to 19, more than double each of the previous three years. The following two years we saw an extreme increase in both the number of SREs requested (37 for 2017 and 42 for 2018) and approved (35 for 2017 and 31 for 2018).

Importantly, it is not just the overall number of SREs approved that is concerning, but also the percentage of applications that are being approved. Before this administration, EPA was approving between 50% and 62% of the petitions that were submitted. Under this administration, the agency granted 95% of the submitted petitions in 2016 and 2017, and 74% of the petitions in 2018 (after prolonged pushback from key agriculture and biofuel industry stakeholders). Additionally, for 2018 three petitions were ineligible or withdrawn while two are pending, so when looking just at the cases that EPA has decided, they have granted 31 of 37, or 84%.

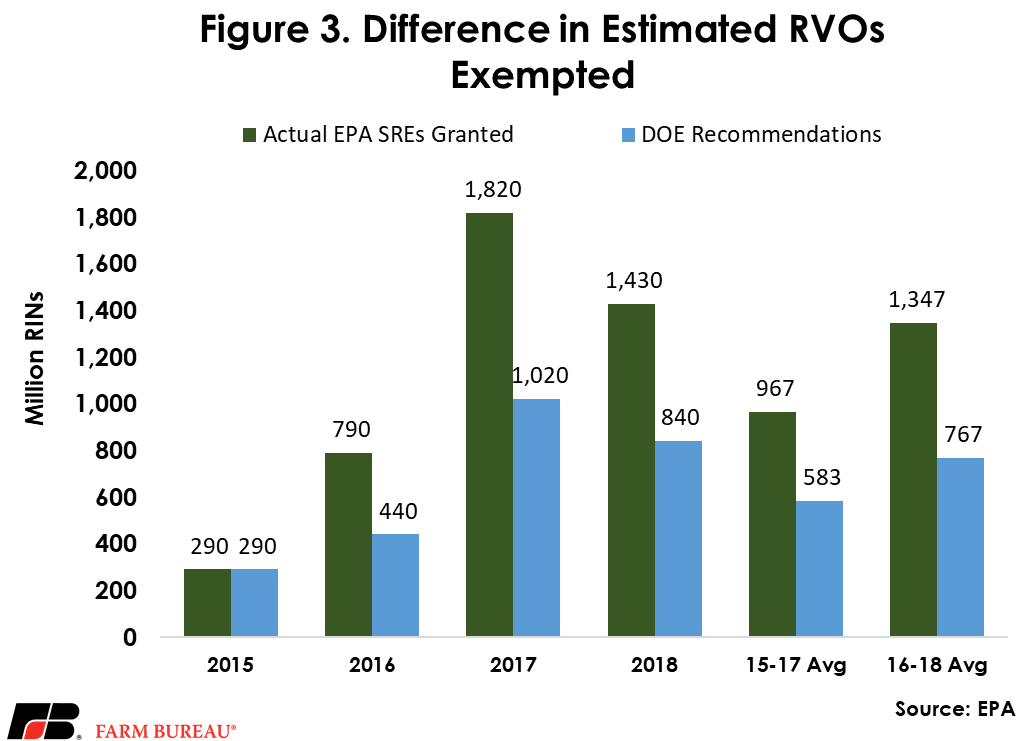

Once the oil refining industry saw how exemptions were being treated under the new EPA leadership, many sought to take advantage of the situation and the number of petitions skyrocketed. It is reported that refineries owned by large companies such as ExxonMobile and Chevron Corp were granted SREs for refineries they own, leading many to question the claim of “disproportionate economic hardship.” SREs dramatically increased the total renewable volume obligations that were exempted. In 2016, an estimated 790 million in renewable volume obligations were exempted, and in 2017 that rose to 1,820 million before dropping to 1,430 million in 2018.

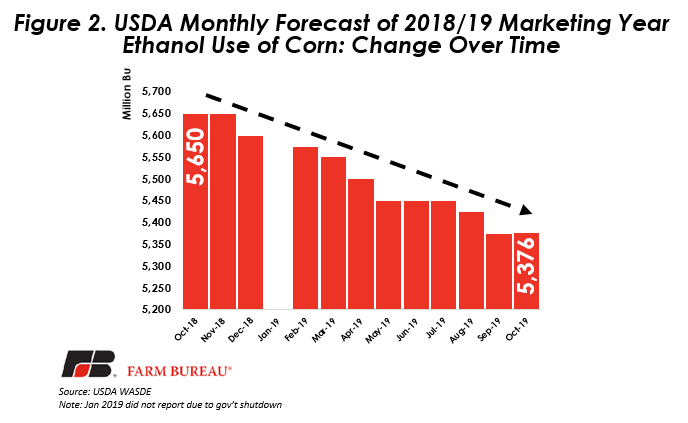

These impacts can filter down to corn used in ethanol production. Figure 2 shows how USDA’s forecast for corn used in ethanol this past marketing year has changed over time. Each month, USDA releases the World Agricultural Supply and Demand Estimates report, which includes a forecast for corn used in ethanol for the year. USDA revises these forecasts over time as they receive new information about the current state of the market. Over the past year, USDA has continuously reduced its estimate for corn used in ethanol in the wake of continuing SRE announcements and as more ethanol plants announced they would idle production. USDA reduced its estimate by nearly 275 million bushels, or 5 percent, over the last year. Moreover, corn used for ethanol production fell by 229 million bushels from the 2017/18 marketing year and is at the lowest level since the 2015/16 marketing year.

What is in the current proposed notice?

The supplemental notice does not change the proposed RFS volumes for 2020 and 2021. Instead it seeks comment on adjustments to the way annual renewable fuel percentages are calculated. The initial announcement hinted that EPA would project the volume of gasoline and diesel that would be exempt in 2020 due to small refinery exemption based on a three-year rolling average of exemptions. While the three-year average would not totally reallocate the lost gallons, it was a step in the right direction and was supported by the biofuels and agricultural industry stakeholders.

Following that announcement, President Trump suggested that EPA could require 16 billion gallons for the ethanol blending mandate. Administrator Wheeler later clarified that the agency would require a net of 15 billion gallons after accounting for the refinery waivers.

Industry groups largely consider the latest announcement to be substantially different than what was originally promised. Frustrated that the proposal does not address the harm caused by the SREs, they worry it will continue to contribute to demand destruction for ethanol, and in turn, reduce demand for corn.

The proposed adjustments in the notice designate that this three-year rolling average will be based on the relief recommended by the Department of Energy, not on actual exemptions granted. This is a key point of contention for the industry as there is often a disconnect between how many gallons are recommended by DOE to exempt through full or partial exemptions and what the actual exemptions end up being. Simply put, DOE recommended a lower number of RVOs be exempted by EPA, EPA disregarded that and exempted a larger number of RVOs. EPA then proposed to account for the actual lost gallons by using the lower DOE numbers it had already rejected, resulting in a certain creative irony.

Figure 3 shows the disconnect between DOE’s recommendations and EPA’s actions. One can clearly see the considerable difference between what DOE suggested and what EPA ultimately decided to issue. Additionally, in the supplemental notice EPA requested comment on whether to use the 2015-17 three-year average rather than 2016-18. This would result in an even larger discrepancy between the rolling average and the actual exemptions in recent years.

Summary

The biofuel and agriculture industries’ attitude changed from one of praise in anticipation of the administration’s expected action to address the harm caused by SREs, to outright dismay less than two weeks later when EPA released its supplemental notice. By proposing to utilize DOE-recommended exemptions instead of actual exemptions in accounting for the billions of gallons of ethanol lost to SREs, this fix does little to restore the demand destruction caused by SREs and further undermines the RFS. Many in the industry feel that this supplemental notice was equivalent to a bait and switch and does not live up to the promises made in the administration’s initial announcement.

The next step in this process is for biofuel and agricultural industry stakeholders to engage with the EPA through the public comment process which is expected to open soon and close at the end of November. Following the public comment period, EPA will issue updated standards for 2020 and 2021 RVOs – one that many in the biofuels and agriculture industry – including corn-state lawmakers -- hope will revert back to original balanced approach to account for SREs by fully capturing historical SREs granted.

Trending Topics

VIEW ALL