Drought Expands Across the U.S.

TOPICS

WeatherAFBF Staff

photo credit: Texas Farm Bureau, Used with Permission

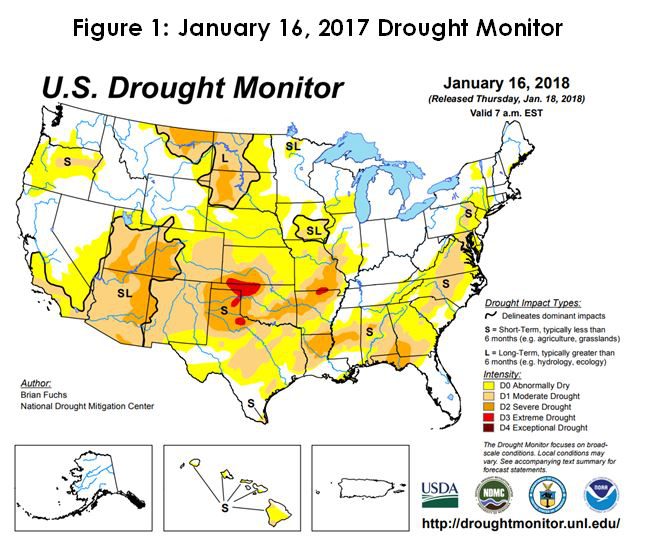

The latest drought monitor released by University of Nebraska at Lincoln showed that over 60 percent of the continental U.S. is in a state of drought. About 27 percent is listed as abnormally dry and another 23 percent is characterized as moderate drought. Last year drought worries centered around the northern Plains and grazing conditions in the Dakotas and across Montana. Those areas still remain dry but the intensity has weakened. Moving into 2018, drought intensity and area is spreading extending over the Southwest, southern Plains and Great Plains. Figure 1 is the Jan. 16 drought monitor.

The National Weather Service Climate Prediction Center indicates that the dryness is likely to continue into the fall, with above average temperatures predicted and below average rainfall expected in spring. This could spell trouble for cattle country, which still has sharp memories of the 2011/2012 drought that resulted in the liquidation of roughly a million head of cattle. A quick comparison of the drought monitors from January 2011 and this January indicate that the dryness is worse now. The La Nina conditions currently present are expected to affect the Northern Hemisphere this winter, with 85-95 percent certainty. However, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration is predicting an ENSO-neutral (neither La Nina nor El Nino) spring.[1] Those forecasts are updated weekly and could change. The Oceanic Nino Index is one measure of the anomalies associated with ENSO and has not been as severe as it was in 2011. However, there is still concern that this drought will intensify.

During the previous drought, one of the largest impacts on feedstuffs was the rise in hay prices. During the 2011-2012 marketing year hay prices rose from $154 per ton to over $180 per ton in Texas. Texas, the largest hay producing state in the country, is already grappling with a hay yield drop of 16 percent at least in part a result of 2017’s Hurricane Harvey. Furthermore, Texas December hay stocks indicate that inventories are down 27 percent, a considerable drop from last year. Even if the drought does not intensify, the lack of moisture and lower stocks could point to higher forage costs. With Texas, the largest forage-raising state, and surrounding states in degrees of drought, forage prices could climb higher rapidly ahead of the first cutting this spring.

[1] http://www.cpc.ncep.noaa.gov/products/analysis_monitoring/lanina/enso_evolution-status-fcsts-web.pdf

Trending Topics

VIEW ALL