Dairy Margin Coverage: What If?

TOPICS

Federal Milk Marketing Order

photo credit: Mark Stebnicki, North Carolina Farm Bureau

John Newton, Ph.D.

Chief Economist

At its base, milk pricing in the U.S. is complicated (How Milk Is Priced in Federal Milk Marketing Orders: A Primer). And the variations in milk checks from farm-to-farm (even neighbors), month-to-month, and cooperative-to-cooperative, and from cooperative to proprietary handler take the pricing complexities to another level. Prices paid to dairy farmers depend upon where the farm is located, where the milk was delivered and pooled, the fat and protein content in the milk and the cooperative- and handler-specific premiums and assessments. Put simply, every dairy farmer in the U.S. likely receives a different price per hundredweight for their milk.

Developing and implementing a farm safety net program outside of crop insurance, i.e., Margin Protection Program and now Dairy Margin Coverage, was complicated by the fact that not only did every dairy farmer have a different price for their milk, but every dairy farmer also likely had different costs of production. Thus, a nationwide approach was taken to deliver targeted income support during times of low milk prices, high livestock feed costs or a combination of the two.

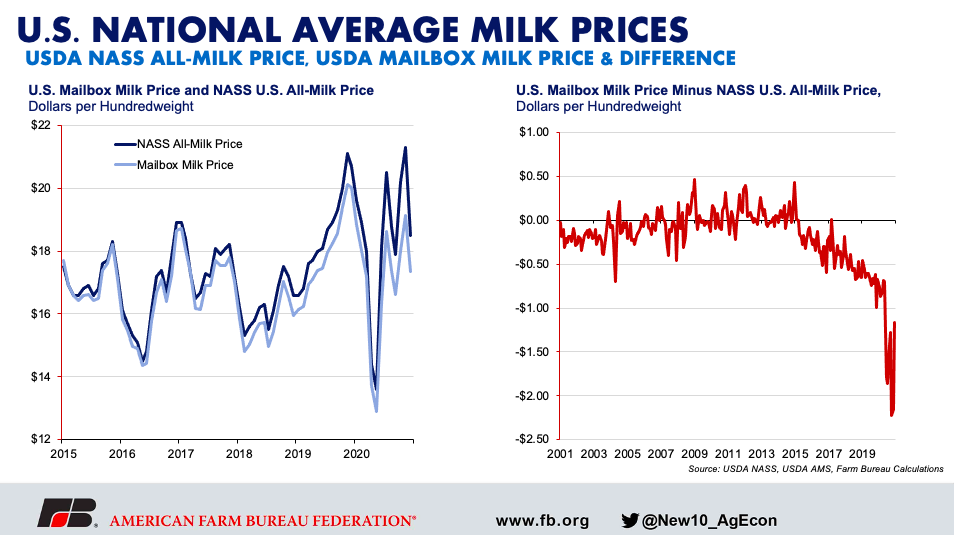

To implement DMC, USDA uses the National Agricultural Statistics Service’s monthly U.S. average all-milk price, i.e., the gross milk price farmers received. The challenge here is USDA publishes another national average milk price called the mailbox milk price, i.e., the net milk price on the check that arrives in the mailbox. The net mailbox milk price includes hauling fees, other authorized deductions and price re-blending due to balancing costs or loads of milk sold at distressed prices, among other items. Historically, these two national average milk prices followed one another very closely.

In recent years, however, these two price series have diverged, and in 2020, a year roiled by COVID-19 demand disruptions, negative producer price differentials and mass depooling (More Negative PPDs and De-Pooling Reignite Federal Milk Marketing Order Debate), the spread between the two milk prices was record-large. For example, in October and November, the USDA all-milk price was more than $2 per hundredweight higher than the national average mailbox milk price. One explanation is the higher-valued milk was not in the pool, and thus was not included in the mailbox milk price calculation.

However, for years now, even before 2020, the U.S. all-milk price has been disconnected from what was happening on the farm, and as a result, the farm safety net is becoming more disconnected from milk prices that farmers are actually receiving (Lack of DMC Payments Does Not Reflect Dairy Farmers’ Difficulties).

Mailbox Milk Price in Dairy Margin Coverage

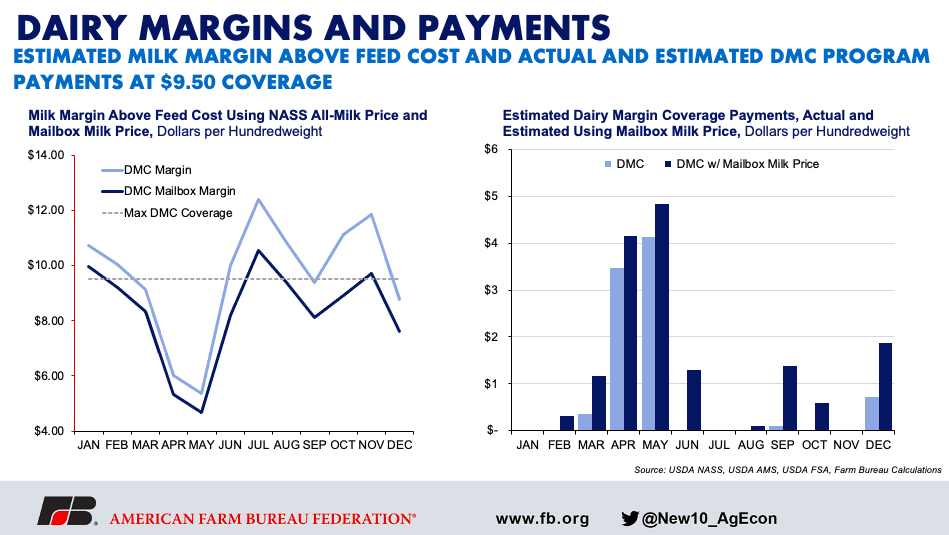

What if the farm safety net used the mailbox milk price instead of NASS’ all-milk price? To answer this question, DMC milk margins above feed costs, monthly program payments, and total DMC program payments were estimated for 2020 using Farm Service Agency enrollment and price data alongside USDA mailbox milk price data.

During 2020, the DMC margin averaged $9.65 per hundredweight and ranged from a low of $5.37 per hundredweight in May to a high of $12.41 per hundredweight two months later in July. For a farm covering 5 million pounds of milk in DMC, program payments totaled more than $36,000, or 73 cents per hundredweight.

Substituting the mailbox milk price in the DMC margin calculation, the DMC margin would have averaged $8.34 per hundredweight and ranged from a low of $4.67 per hundredweight to a high of $10.55 per hundredweight. More importantly, DMC triggered in five months during 2020. Had DMC used the mailbox milk price, DMC would have triggered in nine months during 2020 and would have delivered nearly $29,000 in additional support to a farm covering 5 million pounds of milk. Total DMC payments for an operation covering 5 million pounds of milk would have been more than $65,000 at $1.31 per hundredweight and 80% higher than the current program design.

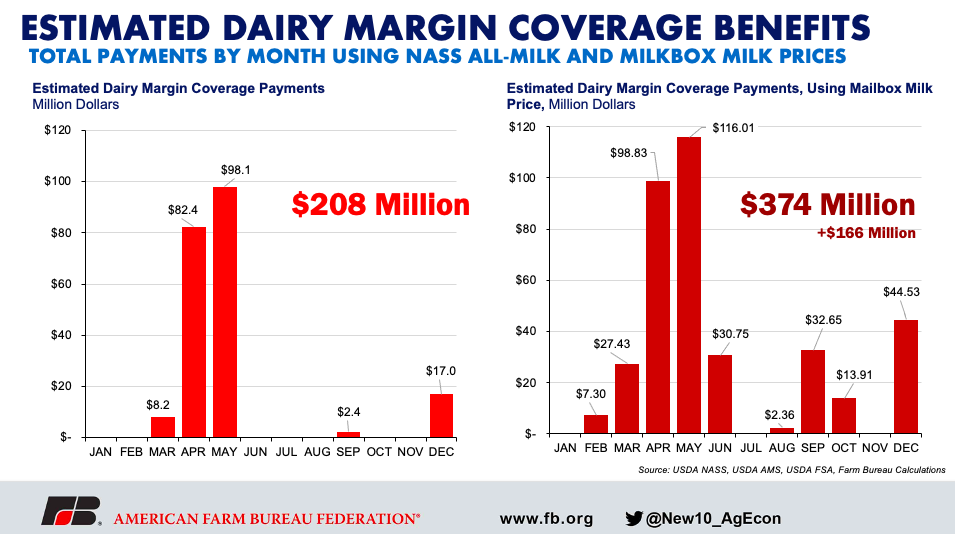

What about total outlays? Data from FSA reveals that more than 28 billion pounds of milk were covered at the highest $9.50 coverage option. In total, DMC covered slightly more than 110 billion pounds of milk during 2020. Based on FSA’s enrollment data, total DMC program payments nationwide for both Tier 1 and Tier 2 coverage is estimated at $208 million (USDA reports $218 million, but likely has more recent enrollment data than what is available online).

Had the mailbox milk price been used in the DMC formula, based on the same enrollment data as before, it is estimated that DMC would have delivered an additional $166 million in support. Total program payments across Tier 1 and Tier 2 are estimated at $374 million.

Upcoming Dairy Policy Debates

Since 2015 there has been a structural change in the relationship between USDA’s all-milk price and their mailbox milk price. During 2020, the spread between these price series became record-large following mass depooling of milk from Federal Milk Marketing Order revenue sharing pools, negative PPDs and COVID-19-related demand disruptions that likely led to higher cooperative re-blending of milk checks across their membership due to increased balancing costs, dumping of milk and milk sold at distressed prices.

To reflect this structural change, some in the dairy industry have proposed adjusting the DMC formula to use the mailbox milk price instead of USDA’s all-milk price. In fact, Farm Bureau delegates recently adopted policy calling for these milk check deductions to be factored into farm safety net programs. The logic: the mailbox price better reflects what’s happening on the farm and should be used to implement Title I dairy programs. During 2020, the use of the mailbox milk price in the DMC formula would have delivered an additional $166 million in program payments to dairy farmers, an increase of 80% compared to the current program design.

The challenge with using the mailbox milk price is multifaceted. First, the mailbox milk price release lags the release of the all-milk price by several months. USDA would need to expedite the calculation of the mailbox milk price for it to be used in the DMC formula. Next, depooled milk would need to be taken into consideration to prevent double-dipping, i.e., farmers with depooled milk and likely higher mailbox milk prices may be overcompensated for low milk prices received by others. The available coverage options too, i.e., $9.50 per hundredweight, may need to be reexamined with a formula change.

Then, given that many of the milk check deductions reflect farmer assessments such as membership dues, hauling charges, balancing costs and re-blending fees, moral hazard exists to the extent that these assessments could be increased and then partially offset by federal program payments from DMC, i.e., higher balancing costs would be covered to some extent by DMC program payments if the mailbox milk price were used. Moral hazard, in this case, is the lack of incentive to protect against higher costs imposed on the dairy farmer. Examples include hauling charges, balancing costs or make allowances.

Finally, despite the low mailbox milk prices in 2020, milk production continues to expand. Some would argue that additional federal support would only further stimulate milk production. Some would also point out the likelihood that the expansion in milk production is not coming from small and medium-sized farms with higher costs of production, but rather the larger operations unlikely to fully benefit from an adjustment in the DMC formula.

Revamping the DMC formula is just one dairy issue ripe for discussion. Add to that the reconsideration of the Class I milk price formula agreed upon in the 2018 farm bill, ways to reduce depooling and the associated negative PPDs, the upcoming debate on make allowances and more broadly FMMO reform and we have one sure thing about dairy policy: there’s a lot to consider – and there will be for some time to come.

Top Issues

VIEW ALL