CRP Participation Has Declined, Despite Rising Program Cap

TOPICS

USDAShelby Myers

Economist

photo credit: AFBF Photo, Morgan Walker

Shelby Myers

Economist

First incorporated into a farm bill in 1985, the conservation title is what some would consider the original Green New Deal. Its voluntary conservation initiatives give farmers and ranchers flexibility to adopt practices in a market-based approach.

Farmers and ranchers are already good stewards of water and land, but the 2018 farm bill, the Agriculture Improvement Act of 2018, provided expanded conservation programs that could increase conservation initiatives. The goal is to improve water quality and wildlife habitats and populations, protecting natural resources and providing many other benefits. The conservation title of the 2018 farm bill spends $60 billion of the $867 billion of mandatory funding required for conservation programs over 10 years, equal to 7% of the bill’s total projected mandatory spending in that timeframe.

The three main programs that make up the conservation title cover working lands and land retirement. The two largest working lands programs are the Environmental Quality Incentive Program and the Conservation Stewardship Program, with a combined dedicated $25 billion over 10 years. Funding for CSP was shifted away from an acreage limitation to limits based on funding. EQIP was expanded and reauthorized with increased funding levels. The largest land retirement program and the focus of the article is the Conservation Reserve Program, with outlays close to $2 billion per fiscal year.

Land Retirement Programs

Land retirement programs pay agricultural landowners for temporary changes in land use or management to achieve environmental benefits. CRP provides financial compensation to landowners who voluntarily enroll highly erodible and environmentally sensitive lands. The compensation comes via a cash rental rate based on the relative productivity of soils within each county and the average cash rent of the county, as determined by the National Agricultural Statistics Service. With that, more productive ground remains in agricultural production, while resource-conserving and wildlife habitat preservation practices are installed on marginal acres. In addition to CRP, there are four other land retirement programs in which CRP acres can be enrolled including the Conservation Reserve Enhancement Program, Farmable Wetlands Program, CLEAR30 and Soil Health Income Protection Program (a pilot program).

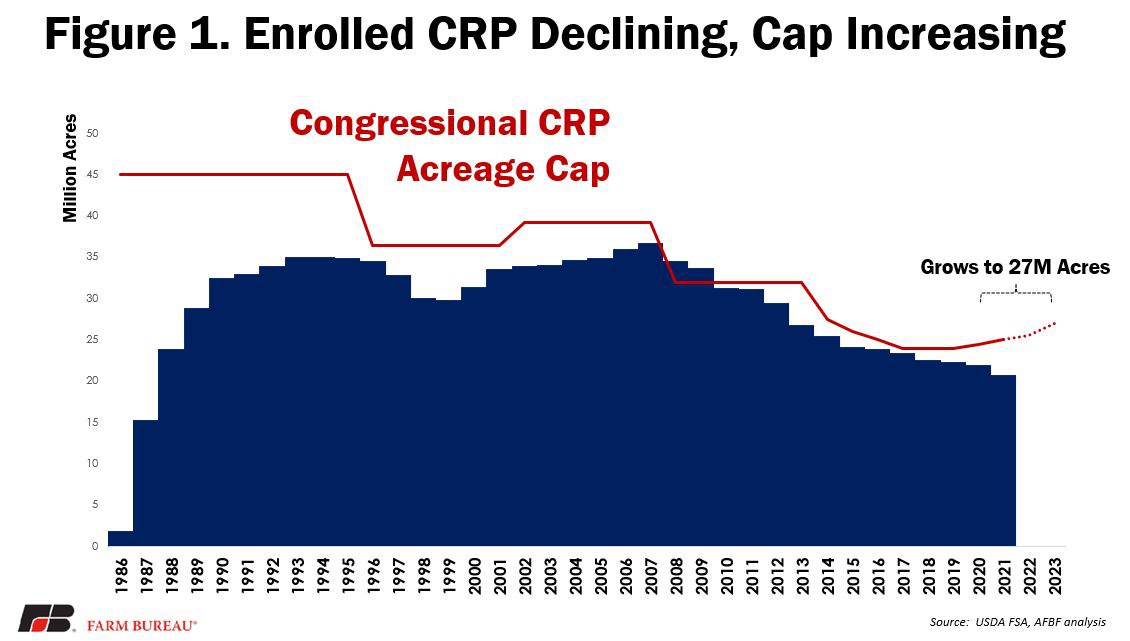

The 2018 farm bill called for incremental increases of enrollment limits in CRP, growing from 24 million acres in fiscal year 2019 to 27 million by fiscal year 2023. For fiscal year 2019, CRP enrollment was capped at 24 million acres; 24.5 million acres in fiscal year 2020; 25 million acres in fiscal year 2021; 25.5 million acres in fiscal year 2022; and 27 million acres in fiscal year 2023.

While the enrollment limits are increasing, actual acreage enrolled has gone in the opposite direction; enrollment for 2021 sits at 20.8 million acres, a little more than 4 million acres below the 25-million-acre cap. In fact, the total number of acres enrolled in CRP has declined every year since fiscal year 2007, although that decline has slowed in recent years, as seen in Figure 1.

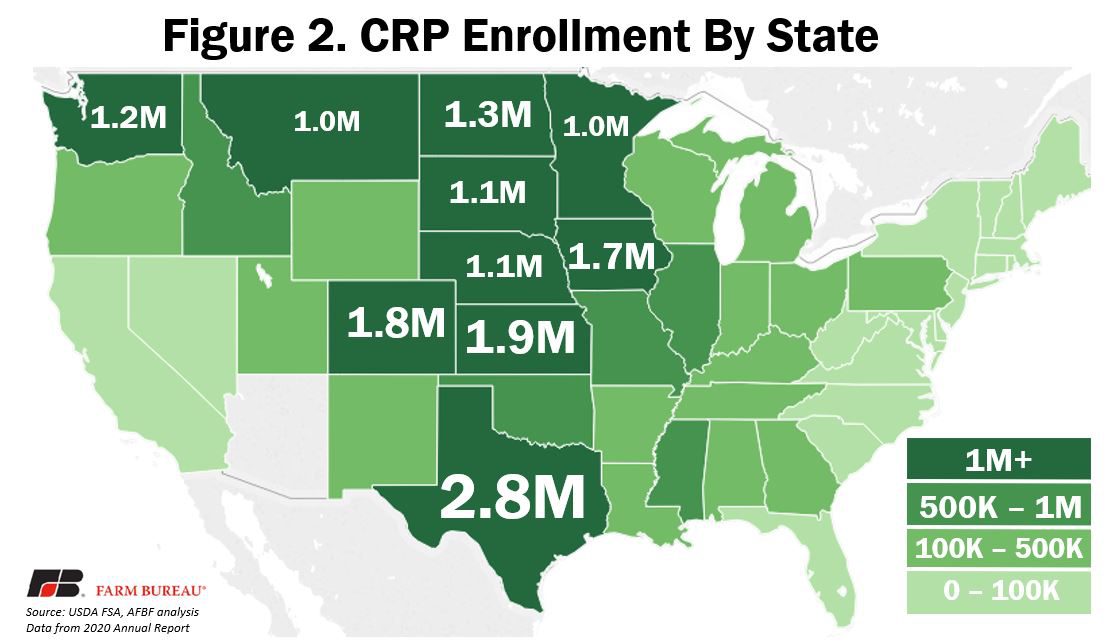

Figure 2 is a map of Conservation Reserve Program enrollment for fiscal year 2020. Texas leads the country in CRP enrolled acres with nearly 2.8 million acres, followed by Nebraska, Colorado and Iowa with 1.9 million acres, 1.8 million acres and 1.7 million acres, respectively. There are 10 states with over 1 million acres enrolled in CRP, and they are largely concentrated in the Plains and neighboring regions, with Washington as an outlier. With fewer than 50,000 acres enrolled in most states in the region, the Eastern U.S. tends to have the fewest enrolled acres.

CRP Rental Rates

Along with increasing the annual enrollment acreage cap, the 2018 farm bill also adjusted CRP rental rates to better align the program with market-based conditions. The change was intended to help CRP more accurately serve its purpose of retiring more sensitive lands without competing with the local farmland market. This would prevent the government from limiting farmers' and ranchers’ access to prime farmland and keep highly productive land in production while using working lands conservation programs.

The 2018 farm bill limited CRP rental rates for general enrollment to 85% of the county average rental rate, while continuous enrollment rental rates were limited to 90% of the county average rental rate. This supports the requirement that the program account for the potential impact on the local farmland rental market of a market-based approach that would improve the availability of farmland for farmers and ranchers. The current maximum rental rate NRCS can offer for CRP is calculated in the following ways:

General CRP Rental Rate Cap: CRP rental rate < 85% of county average rental rate

Continuous CRP Rental Rate Cap: CRP rental rate < 90% of county average rental rate

It is important to note that the maximum CRP rental rates can change year-to-year since they are coupled with the county average rental rate. This means that rising or declining county rental rates can impact the maximum amount of rent CRP can offer in a given contract year.

USDA Announces Reopened Enrollment for 2021 CRP

With 2021 CRP enrollment sitting at 20.8 million acres, USDA announced plans to reopen enrollment to add up to 4 million new acres to the program using increased rental rate payments that are tied to soil productivity and additional incentives for climate-smart practices. The department will also expand the number of incentivized environmental practices allowed under the program. While USDA will still have to adhere to the CRP rental rate caps established by Congress, it is unclear whether the additional incentives will be sufficient to increase CRP enrollment up to the statutory cap of 25 million acres given rising commodity prices. This announcement will force landowners to make the decision to either accept a CRP rental rate with additional climate-smart practice incentives that will need to be implemented or follow current market signals and rising commodity prices that incentivize keeping land in production. While the farm bill was explicit about capping enrolled acres in CRP and capping CRP rental rates, it did not require USDA to fully enroll acres into CRP up to the fiscal year limit.

Summary

When the conservation title was first included in the 1985 farm bill, it provided farmers and ranchers with voluntary, market-based incentives to adopt conservation practices. While the 2018 farm bill increased enrollment limits in CRP, actual acreage enrolled has declined. The adjusted CRP rental rates implemented in the 2018 farm bill better align the program with current local farmland market conditions to prevent the government from barring farmers and ranchers from accessing prime farmland. So far, this change has encouraged farmers to install resource-conserving practices on environmentally sensitive farmland and helped keep highly productive land in production using good stewardship practices that can preserve wildlife habitats, soil and water. With USDA’s most recent CRP announcement to reopen enrollment, time will tell whether or not landowners take incentives added in the CRP rental rates up to the statutory caps or if they keep land in production to meet rising demand for commodities currently driving increased prices.

Trending Topics

VIEW ALL