Crop Insurance Guarantees Fall in 2020

TOPICS

Trade

photo credit: Arkansas Farm Bureau, used with permission.

John Newton, Ph.D.

Former AFBF Economist

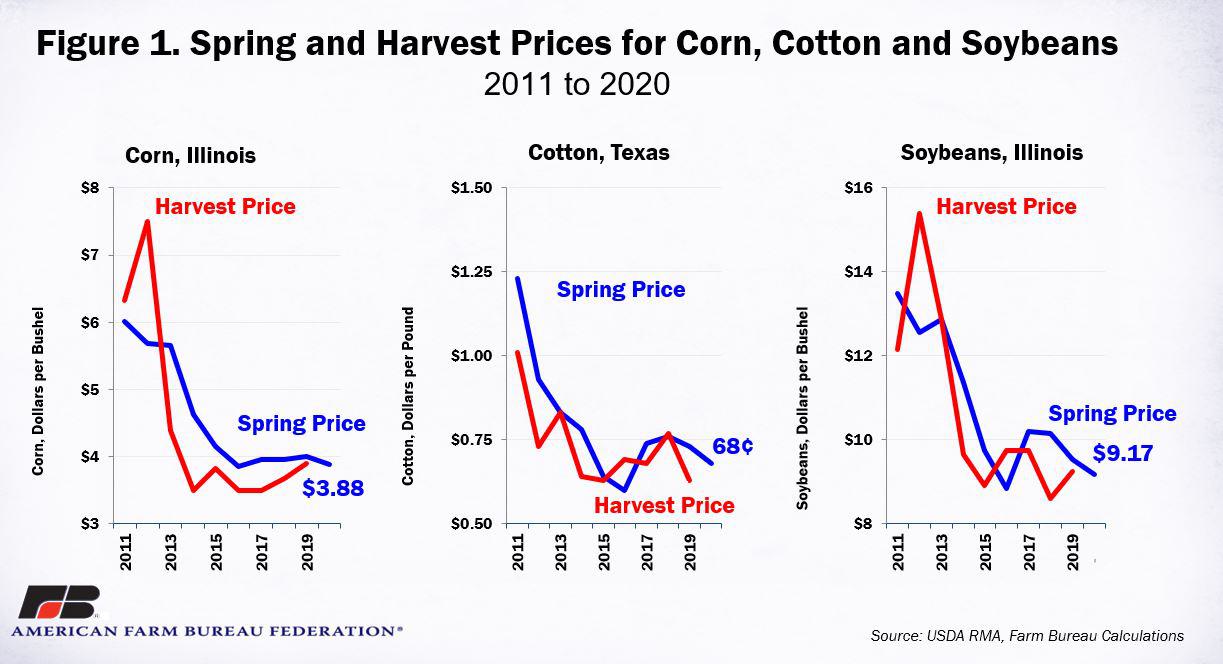

USDA’s recently released spring crop insurance prices for corn and soybeans were among the lowest in the last 10 years. Cotton prices dropped as well, down nearly 7% from last year. Not only is crop insurance a key risk management tool for farmers, creditors often use the spring crop insurance prices and revenue to establish a minimum income level (but also including other farm financial indicators) and determine how much credit they will extend to a farmer. Additionally, many monitoring the markets use the spring prices to evaluate potential corn and soybean acreage shifts.

Background

Each year, in advance of the planting season, USDA’s Risk Management Agency recalibrates crop insurance protection based on expected commodity prices and risk in the market. During a month-long February survey period, market expectations for prices are averaged to determine the spring crop insurance price. When combined with a farmer’s yield history, the spring prices and yield determine the level of revenue protection available during the crop year.

Providing an indemnity payment in the event of a crop loss or a decline in crop revenue, crop insurance is an important risk management tool for producers. The spring crop insurance guarantee is also important because creditors often use it to help establish the borrowing capacity they are willing to extend to a farmer.

Anecdotally, many lenders will extend to a borrower a line of credit approximately equal to 70% to 80% of the crop insurance revenue guarantee, i.e., the minimum income level. For example, a $4 per bushel corn price and a 200 bushel per acre yield with 80% crop insurance coverage could allow a borrower to receive financing of approximately $448 to $512 per acre, equivalent to $2.24 to $2.56 per bushel.

Importantly, crop insurance is not the only financial barometer a lender may use. Lenders certainly review many farm financial indicators such as debt-to-asset or debt-to-equity ratios among others to determine the lending volume. Nevertheless, lower crop insurance spring prices do reduce the borrowing capacity of farmers as the minimum guaranteed income is lower.

2020 Spring Crop Insurance Prices

Following two consecutive crop years with retaliatory tariffs, expectations for record corn production and rising stockpiles in 2020, a significant rebound in soybean acreage and production this year and large domestic and global supplies of cotton, i.e., 2020 Outlook Projects Principal Crops Rebound, RMA’s Crop Insurance Price Discovery tool revealed lower spring crop insurance prices for corn, cotton and soybeans in 2020.

The 2020 corn crop insurance price was announced at $3.88 per bushel, down 12 cents, or 3%, from last year. The 2020 spring price is the lowest since 2016’s $3.86 per bushel and the second lowest in the last decade. For soybeans, the spring price was announced at $9.17 per bushel, down nearly 4%, or 27 cents per bushel. Like corn, the spring soybean price is the second lowest in a decade, behind only 2016’s $8.85 per bushel. The spring cotton price was announced at 68 cents, down 5 cents per pound and nearly 7% lower than 2019’s price.

Historical spring and harvest prices for corn, soybeans and cotton are highlighted in Figure 1. These crop insurance prices, and thus the revenue guarantees, were determined by averaging the Chicago Board of Trade (corn and soybeans) and Intercontinental Exchange (cotton) futures contract settlement prices during a month-long price discovery period. Spring prices for corn, cotton and soybeans are determined by averaging the new-crop futures contract settlement prices (December for corn and cotton, November for soybeans) during the month-long February price discovery period.

Clue for Acreage?

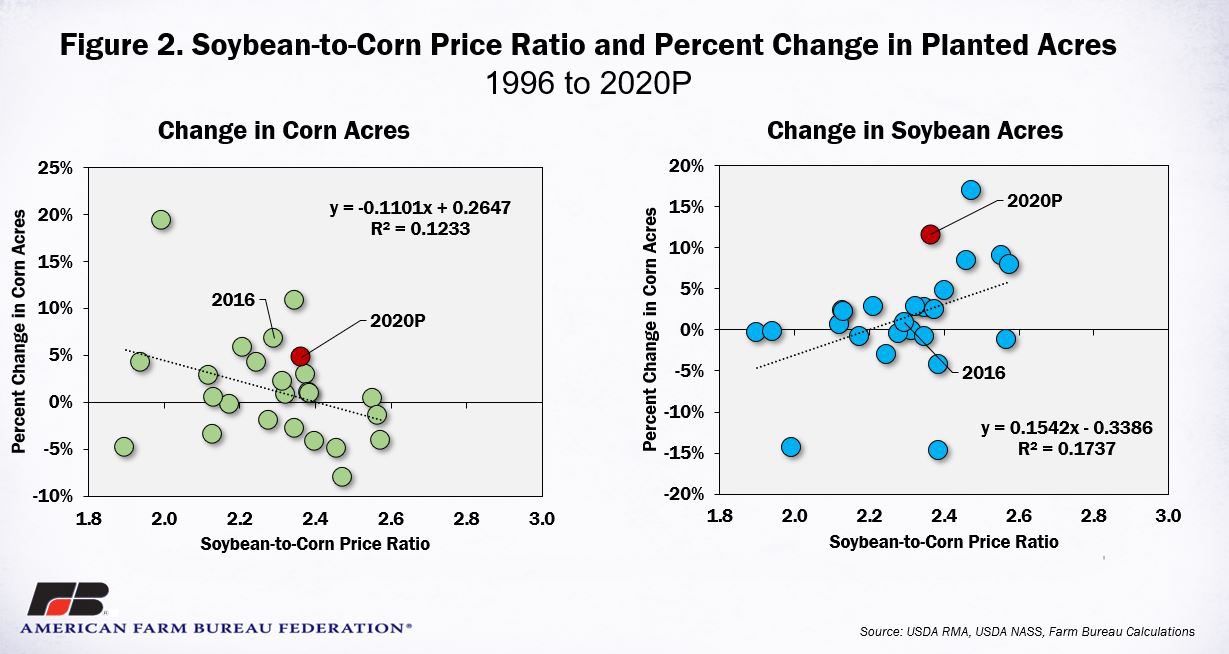

While the spring price discovery is important for crop insurance policies, many in the trade also use the spring prices to evaluate potential acreage shifts for corn and soybeans during the upcoming crop year. USDA’s recent Agricultural Outlook Forum provided a first look at acreage projections for cotton and grains and oilseeds for the 2020/21 crop year. Corn acres were projected at 94 million acres, up 4.8%, or 4.3 million acres, from the prior year. Soybean acres were projected at 85 million acres, up nearly 12%, or 8.9 million acres, from 2019. Combined, corn and soybeans are expected to add more than 13 million acres in 2020.

A scatterplot of the spring soybean-to-corn price ratio relative to the percent change in planted acreage for corn and soybeans indicates that a price ratio above 2.4 leads to fewer corn acres, while a ratio above 2.2 leads to additional soybean acres. Note, that the low R-squared indicates that the linear regression models are a poor fit and have a wide variance around the trend line.

The 2020 spring soybean-to-corn price ratio was 2.36, down slightly from last year's 2.39, and the lowest since 2016’s 2.29. In 2016, the last time the spring price ratio was as low, planted area of corn increased by 6 million acres or 7%, and soybean acreage increased by 1% or 790 million acres. USDA is currently on the higher end of the historical trend, projecting large increases in both corn and soybean planted area in 2020. The likely reason is the record prevent plant acreage in 2019 makes acreage changes year-over-year an outlier for 2020 (Prevent Plantings Set Record in 2019 at 20 Million Acres).

Summary

USDA’s Risk Management Agency recently released spring crop insurance prices that were lower in 2020 for corn, cotton and soybeans due to trade-related demand disruptions, large inventories and record corn production anticipated in 2020. The corn crop insurance price was announced at $3.88 per bushel, soybeans were $9.17 per bushel and cotton was 68 cents per pound. In the case of corn and soybeans, the spring prices were among the lowest in the last decade and are likely to adversely impact farmers’ borrowing capacity in 2020.

Importantly, these price guarantees are not fixed. Many producers elect to purchase the harvest price option, which utilizes the maximum of the spring or harvest price to determine if a farm has suffered a loss and may assist growers by indemnifying at the replacement value of the crop (if the harvest price is greater than the spring price). The potential exists for harvest prices to increase during the growing season if there is another adverse weather event or demand accelerates on the back of recently signed trade agreements. Harvest prices could also decrease if supplies are larger than anticipated, or demand is lower than currently projected – the latter being an outcome that is increasingly likely for each day that COVID-19 weighs on markets and global supply chains.

Trending Topics

VIEW ALL