Coronavirus Sends Crop and Livestock Prices into a Tailspin

TOPICS

Wheat

photo credit: Colorado Farm Bureau, Used with Permission

John Newton, Ph.D.

Former AFBF Economist

Just as the first case of COVID-19 was confirmed in Wuhan, China, on or around Jan. 14, the United States and China signed a long-awaited Phase 1 trade deal (China: What Does it Mean Now?). China’s all-encompassing response to the outbreak, including self-distancing and stay-at-home protocols, raised concerns about their ability to meet their commitment to purchase more than $40 billion in U.S. agricultural products across 2020 and 2021. The possibility of tapping into the agreement’s “act of God” clause (Article 7.6) also emerged. The clause allows for Phase 1 commitments to be altered if an unforeseeable event outside the control of each party delayed implementation or the timing of purchases, e.g., COVID-19.

For the better half of two months commodity prices were mostly flat to lower as U.S. commodities markets waited for evidence that the Chinese would live up to their Phase 1 commitment. Then, in early March, people in the U.S. began testing positive for COVID-19. To facilitate self-distancing guidelines recommended by the CDC, by March 16 all but essential services in the U.S. economy were shut down.

Commodity futures markets were roiled by the near zeroing out of demand that came with school, restaurant and bar closures, reduced demand for gasoline and ethanol, and projections for negative economic growth across the entire U.S. economy.

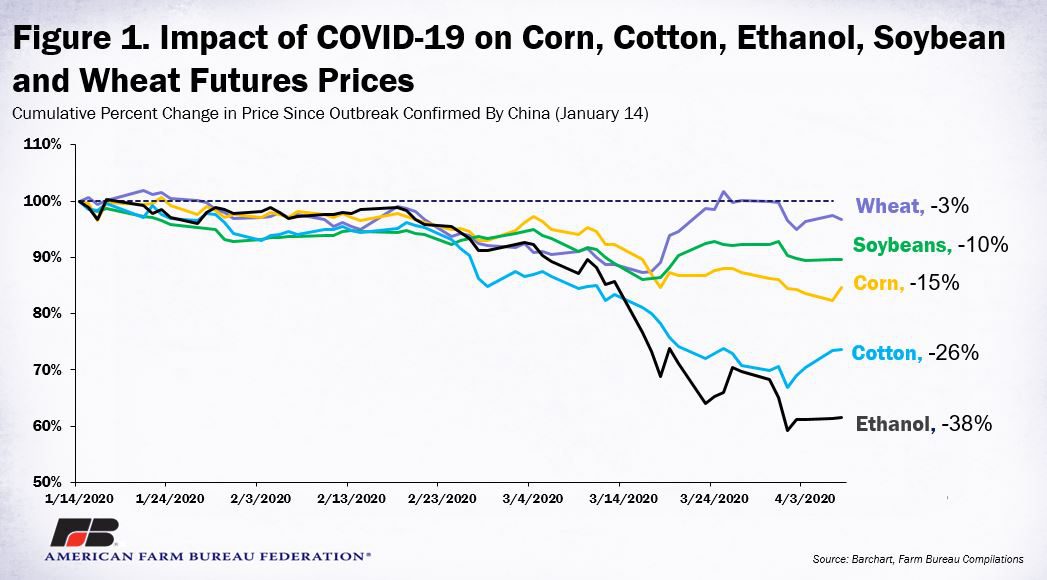

Impact on Crop Futures Prices

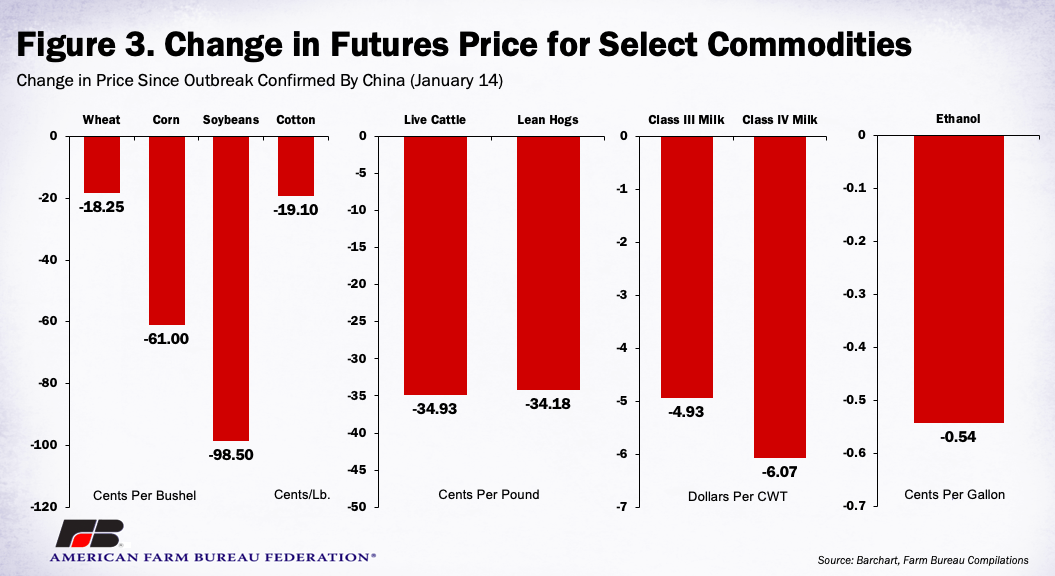

Since Jan. 14, the May futures price for corn has fallen by 15%, or 61 cents per bushel, to $3.35 per bushel. The decline in the corn price is tied to demand uncertainty that has followed the near 40% drop in ethanol futures prices, which now stand at 87 cents per gallon. Prospects for 97 million acres of corn planted in 2020 also weighed heavily on corn prices, i.e., 2020 Prospective Plantings: Corn Soars, Soybeans Bounce, Wheat Falls. The May futures price for soybeans has fallen by 10%, or nearly $1, to $8.57 per bushel.

The higher demand for wheat-based products in U.S. groceries, Chinese purchases of wheat and the fact that winter wheat has already been planted help to support wheat prices. The May wheat futures price was down only 3%, or 18 cents per bushel. The May futures price for cotton, a product heavily dependent on manufacturing capacity abroad, declined by nearly 30% to 53 cents per pound. Figure 1 highlights the change in crop and ethanol futures prices since COVID-19 gripped the U.S.

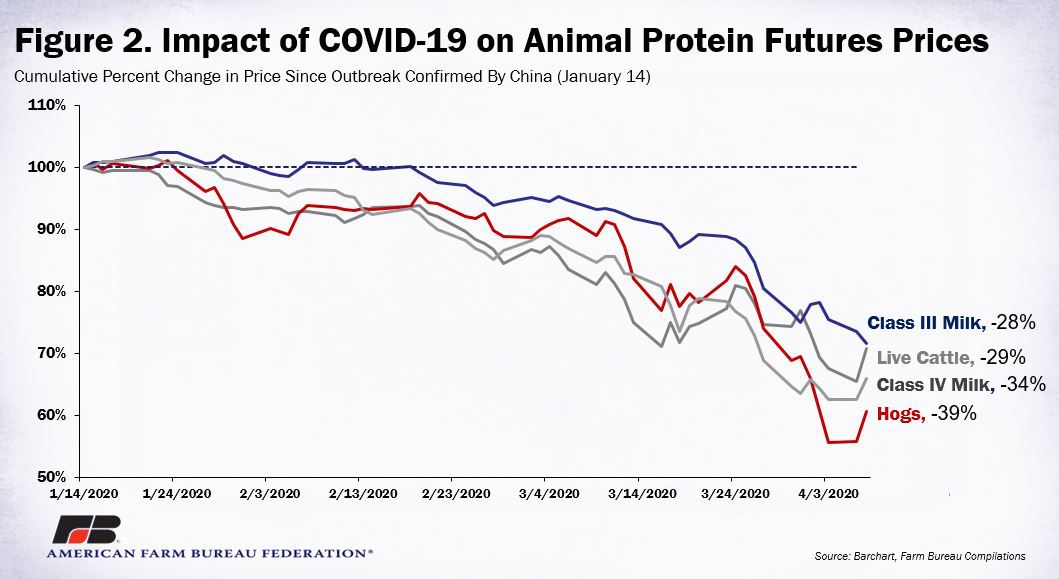

Impact on Livestock Futures Prices

A recent Market Intel article reviewed the impact of COVID-19 on wholesale beef prices and cattle futures prices (Pandemic Injects Volatility into Cattle and Beef Markets). Since Jan. 14, both June live cattle and lean hog futures prices have declined by more than 30% -- lean hogs are at nearly 40%. Live cattle futures prices settled at approximately 85 cents per pound, down 35 cents per pound since mid-January. The lean hog futures price settled at nearly 53 cents per pound, down 34 cents per pound.

Like cattle and hogs, milk futures prices have also fallen sharply. The May futures price for Class III milk (used to produce cheese) has fallen by nearly $5 per hundredweight to approximately $12.50 per hundredweight – a 28% decline. The futures price for Class IV milk (used to produce nonfat dry milk) had a more significant decline, falling by more than $6 per hundredweight, or 34%, to less than $12 per hundredweight. In response to the demand destruction for dairy associated with restaurant and school closures (albeit not in the beverage milk case) as well as the sharp downturn in prices, many milk cooperatives and processors were dumping distressed loads of milk. Figure 2 highlights the impact on livestock-based futures prices and Figure 3 highlights the dollar-value change in select agricultural futures prices.

Summary

Futures prices are the markets’ expectation of a commodity’s value at a specific future point. It gives the holder of the futures contract the obligation to buy or sell a specific volume of a commodity at a specified price, e.g., 200,000 pounds of milk or 5,000 bushels of corn.

The economic uncertainty related to the impact of COVID-19 on the global economy and the demand destruction for many agricultural products contributed to significant price declines for ethanol, crops and animal proteins. The decline in futures prices likely coincided with declines in cash market prices as well.

While these commodity futures have declined significantly, one thing is certain, these futures prices are going to change. As more information emerges related to the duration of the COVID-19 self-distancing guidelines and a potential recovery is in sight, demand could rise, and increased prices could follow.

For more immediate support, the financial assistance in the CARES package will allow USDA to craft financial assistance packages such as direct payments, food purchasing programs, and cost-sharing programs to assist farmers who have experienced these significant price declines and loss of markets related to COVID-19, i.e., What’s in the CARES Act for Food and Agriculture.

Trending Topics

VIEW ALL