Congestion at West Coast Seaports Hinders Trade Boom

TOPICS

Transportation

photo credit: Getty Images

Veronica Nigh

Former AFBF Economist

Daniel Munch

Economist

Getting back to normal? A new normal? The lingering effects of COVID-19’s shock to global trade have resulted in a backlog of container ships waiting to unload outside the West Coast’s most critical shipping ports. Persisting congestion and related logistical obstacles threaten U.S. farmers’ and ranchers’ ability to meet much-welcome increases in foreign demand.

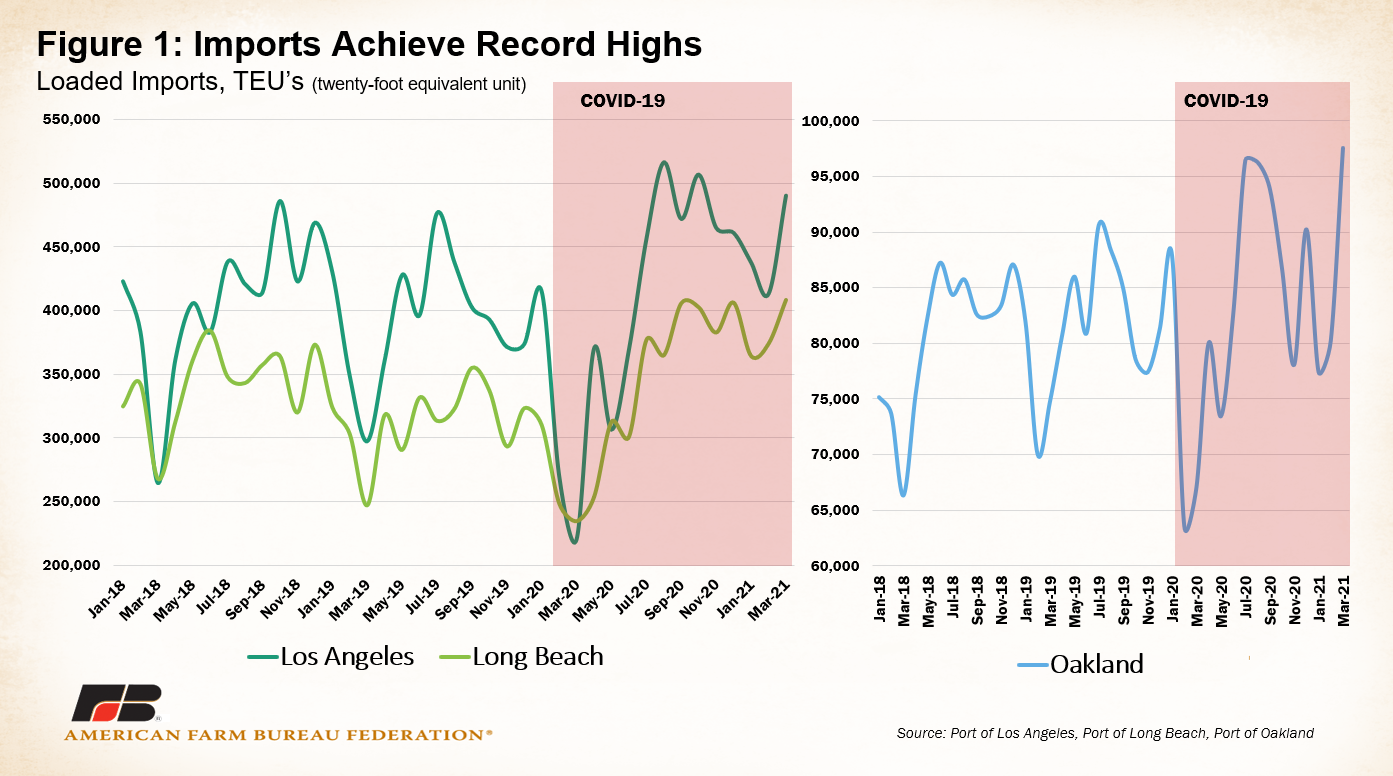

Imports dropped precipitously in the early months of COVID-19, but they began rising again during the summer of 2020 and haven’t stopped. Mirroring the relaxation of many pandemic related restrictions, consumers – with money in hand - entered 2021 eager to spend on a variety of goods and services. Fueled by near-record personal savings rates and stimulus checks, retail consumption of goods is outpacing traditional first and second quarter levels, with total U.S. imports for the first quarter of 2021 up by $138 billion from the first quarter of 2020. Typically, during the first half of the year, shipping companies and seaports prepare for trade increases that occur in the second and third quarters, which are high-consumption months driven by the holiday season and back-to-school shopping.

Los Angeles and its sister port of Long Beach are the two busiest ports in America. Combined with Oakland, these three California seaports are the primary ports for containerized trade with Asian markets. Demand from a country full of pent-up spending energy -- and money -- has pushed all three ports to record import levels over the past year. First quarter 2021 container imports were up 39% from year-over-year values.

The crush of imports has been challenging for the three ports. Backlogs of anchored container ships, which could normally be counted on one hand, reached as high as 40 in February at the ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach. Anchored ship numbers have since decreased to the low 20s and high teens but still present a major bottleneck to the movement of goods. The Port of Los Angeles also reported a 6.1-day waiting period for unloading and docking space during the final week of May 2021; it is usually within a day – at most. Constraints in staffing at trucking terminals contributes to added unloading times.

California’s seaports in Los Angeles, Oakland and Long Beach are also important export terminals. On the export side, these ports have also been extremely busy. First quarter 2021 container exports were up 36% from year-over-year values. Importantly, Los Angeles, Oakland and Long Beach are the first-, second-, and third-largest ports for containerized waterborne U.S. agricultural exports, respectively, in the United States.

Elevated imports and exports have caused considerable congestion both on the water side and on land as the ports filled with the extra containers. In an effort to avoid congestion and to get containers back to Asia generally and China specifically as quickly as possible so that they can be refilled with more import goods, there has been an increase in the shipment of empty containers out of these three ports. Some consider it more efficient to ship empty containers, rather than waiting for export goods to be loaded, which has led to a significant decline in the number of containers available to agricultural exporters.

Across California’s three major ports, empty containers in the first quarter of 2021 jumped from a first quarter 2018-2020 average of 1.16 million TEUs (20-foot equivalent units) to 1.81 million TEUs, a 56% increase. Compared to first quarter 2020 alone, the first quarter of 2021 represents an 80% jump in empty export container units. Accessibility to export containers has been further limited by record shipping costs and harmful surcharges. With these factors combined, the ability for farmers and ranchers to fulfill oversees contracts has been significantly impacted, with some estimations nearing $1.5 billion in lost agricultural exports.

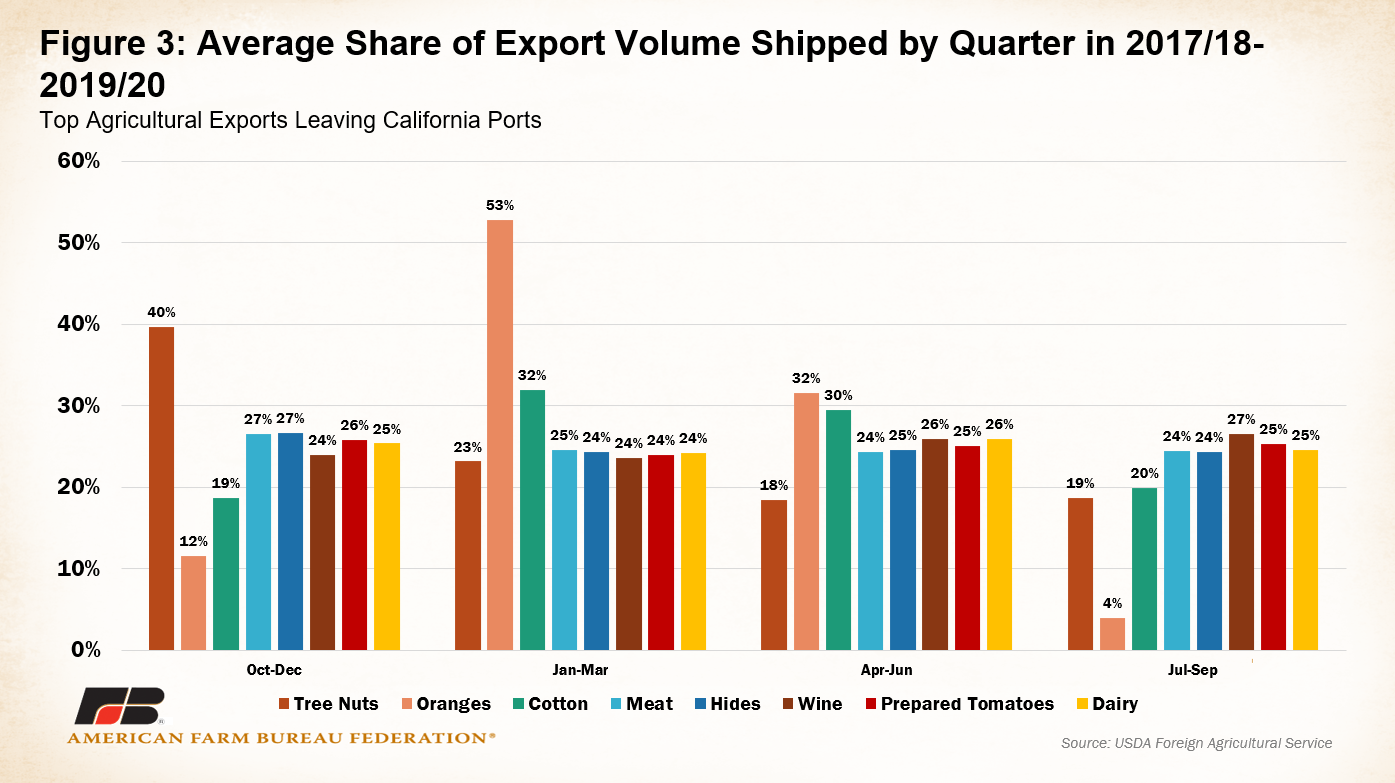

While the ports of Los Angeles, Oakland and Long Beach are important for agricultural exports overall, they are especially vital to some agricultural commodities. As displayed below, California ports support well above or near 50% of all U.S. exports for numerous agricultural commodities. For example, 75% or more of U.S. exports of tree nuts, oranges and prepared tomatoes are exported from the combined Los Angeles, Oakland, and Long Beach area. More than 60% of U.S. exports of cotton and hides and skins, approximately 50% of U.S. meat and wine and 30% of U.S. dairy ship from California ports. Between 2016 and 2020, annual U.S. exports from California ports of just these products averaged nearly $22 billion.

Increased foreign demand for U.S. agricultural products exacerbates the need for container access and logistical solutions to Western port delays. Furthermore, the seasonal nature of some agricultural products makes finding a resolution to port delays critical. For example, oranges and cotton are historically exported at higher rates between January and May, while edible nuts peak between October and December- all especially pressured by port delays since October of last year. Hurdles in sellers’ abilities to meet foreign obligations limits future revenue expectations and stresses relations between foreign partners.

Summary

With generally positives signs of growth across markets, a bottleneck of container ships lingers at Western ports as a COVID-19-induced barrier to much-needed revenue relief. Persisting delays at some of the most economically valuable seaports for U.S. agricultural commodities threaten the bottom lines of farmers and ranchers who rely on foreign outlets to sell their products. These burdensome setbacks have further implications on commodities reliant on seasonal export demand in the affected months. At a time of relatively tight supply and high prices, the orderly movement of goods and services is vital to continued recovery from pandemic-related supply-chain shocks.

Trending Topics

VIEW ALL