China: What Does it Mean Now?

photo credit: Sgt. Mikki Sprenkle/Public Domain

Veronica Nigh

Former AFBF Economist

Today, the United States and China signed a long-awaited Phase One trade deal that, as expected, substantially addresses trade in food and agricultural products. Under the agreement, China has signaled it will purchase and import on average at least $40 billion annually of U.S. food, agricultural and seafood products. However, the main text doesn’t provide much description as to how that figure will be achieved.

Setting the Stage

From January through November 2019, U.S. ag exports to China totaled $12.3 billion, compared to $8.7 billion during the same period in 2018. The year-to-date export value in 2019 is significantly higher than the previous year because of increased purchases that began in June. December export data won’t be available until February 5, but estimations can be made based on previous months performance. However, given the upward trend in purchases, November 2019 exports, reaching $2.2 billion, were significantly higher than November 2018 exports of $426 million. This sizable difference between monthly export performance in 2018 and 2019 makes estimating total 2019 ag exports to China ripe for error, though projecting that December 2019 exports will come in at $2 billion doesn’t seem like a stretch given November 2019 export performance and the pace of fresh, chilled and frozen pork product exports to China. If December exports reach $2 billion, U.S. ag exports to China in 2019 would reach approximately $14.3 billion – up $5.1 billion, or 56%, from the previous year.

There's more than one way to peel an orange

According to U.S. Trade Representative fact sheets, “China has agreed to purchase and import on average at least $40 billion annually of U.S. food, agricultural, and seafood products, for a total of at least $80 billion over the next two years.” Further, in Chapter 6 of the agreement, some guardrails around the $40 billion average are added: “For the category of agricultural goods identified in Annex 6.1, no less than $12.5 billion above the corresponding 2017 baseline amount is purchased and imported into China from the United States in calendar year 2020, and no less than $19.5 billion above the corresponding 2017 baseline amount is purchased and imported into China from the United States in calendar year 2021.” Finally, the factsheet adds, “on top of that, China will strive to import an additional $5 billion per year over the next two years.”

There are several key elements to unpack in USTR’s statement. One is the reference to U.S. agricultural imports of “on average at least $40 billion.” This element is important because it does not commit China to import $40 billion each year, but rather gives China flexibility for different levels of imports in 2020 and 2021; these could be significantly different. After all, $1 billion and $79 billion and $40 billion and $40 billion both average to $40 billion. The key to understanding the Chapter 6 component is knowing that U.S. ag exports to China in 2017 were $19.5 billion. If U.S. ag exports in 2020 increase by the $12.5 billion minimum, that would mean that U.S. ag exports to China in 2020 will be at least $32 billion. If U.S. ag exports in 2021 increase by the $19.5 billion minimum, that would mean that U.S. ag exports to China in 2021 will be at least $39 billion. If China only imports the minimum amount in 2020 and 2021, the total value of imports over the two-year period will be $71 billion. This is where the final element of China striving to reach an additional $5 billion per year comes into effect. If this is achieved the total value of imports over the two-year period would reach $81 billion. Certainly, exports closer to $40 billion each year would seem relatively easier to achieve, but as we watch ag exports to China over the next two years, we should keep in mind that China has a lot of flexibility in how it achieves the $80 billion commitment.

Full Market Basket

The agreement signed today between the U.S. and China echoes the purchase value levels discussed in the press for several months. Over this time, there has been considerable discussion about whether $40 billion-$50 billion in U.S. ag exports to China are feasible. Doubt has crept in for a variety of reasons. One primary concern is the retaliatory tariffs China is still applying on nearly 100% of U.S. ag exports. The tariffs, despite the agreement reached today, will remain in place. The second reason is that the U.S. has never come close to exporting $40 billion in ag products to China. The closest we have ever gotten was around $26 billion in 2012.

USTR’s factsheet sheds some light on how $40 billion could be achieved. The factsheet states that “products will cover the full range of U.S. food, agricultural, and seafood products.” Food, agricultural and seafood products is a more comprehensive definition of agriculture than is often used. When agriculture-related products, like distilled spirits, ethanol, biodiesel, forest products and fish products, are included, peak U.S. food, agricultural and seafood product exports to China were nearly $29 billion in 2013. Obviously, the more comprehensive the definition of agriculture, the easier it will be to reach the export goal, but $29 billion is still a long way from $40 billion.

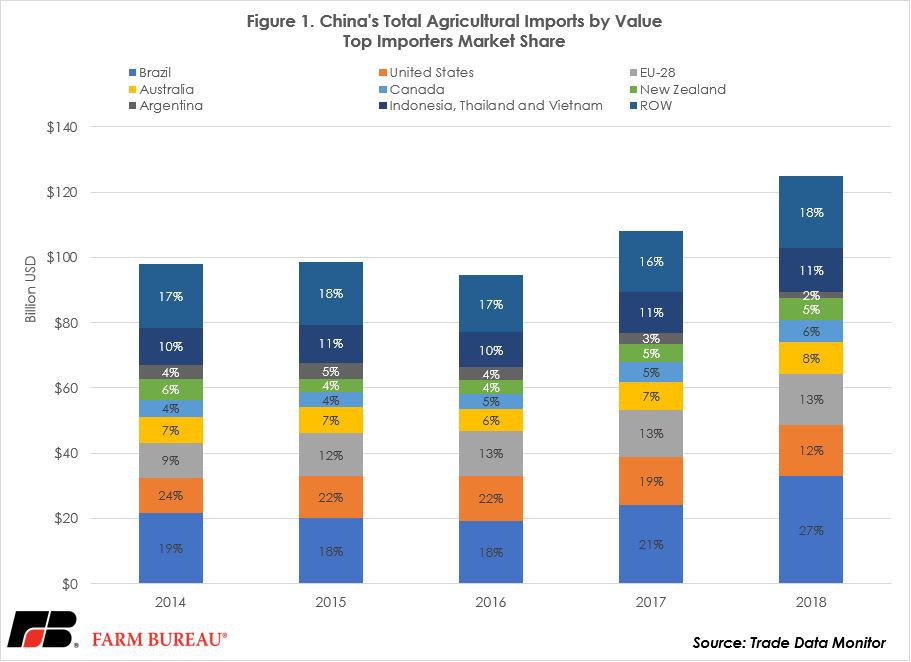

In order to properly consider whether $40 billion is achievable, it’s important to understand how the U.S. fits in China’s overall ag import landscape. From that perspective, the U.S. is a top-five supplier of ag imports to China but has not been the top exporter since 2016. Figure 1 highlights that the top role has belonged to Brazil since 2017 and that competition for Chinese consumer dollars is fierce. In 2018, Brazil, the EU-28, the United States, Australia, Canada, New Zealand, Argentina, Indonesia, Thailand and Vietnam accounted for 82% of China’s lucrative $124 billion ag import market. The rest of the world split the remaining 18%.

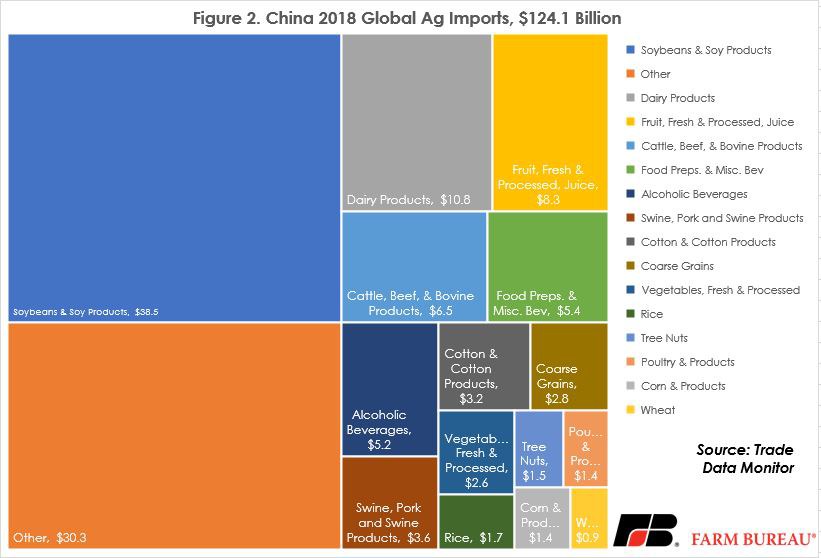

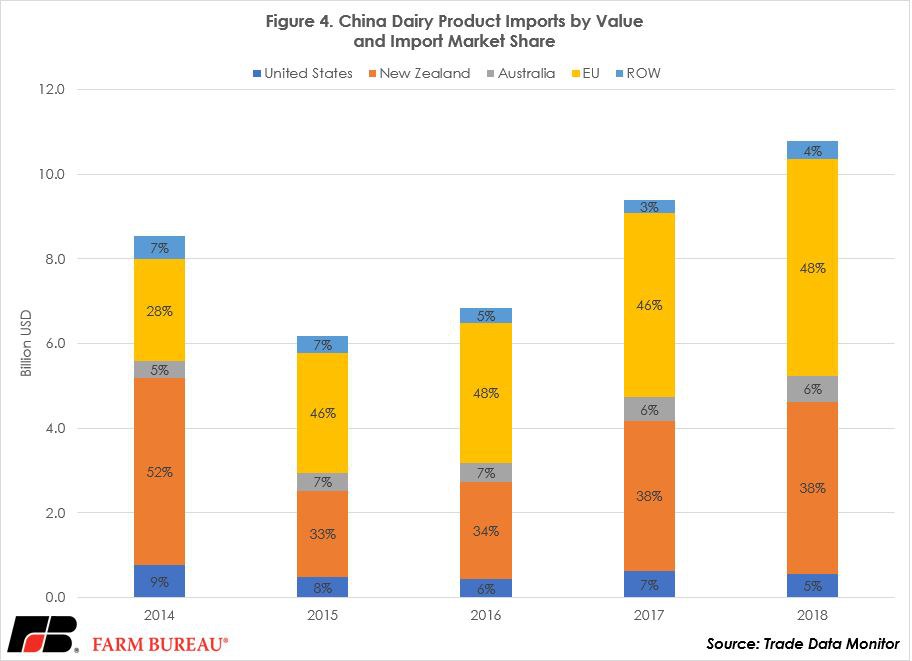

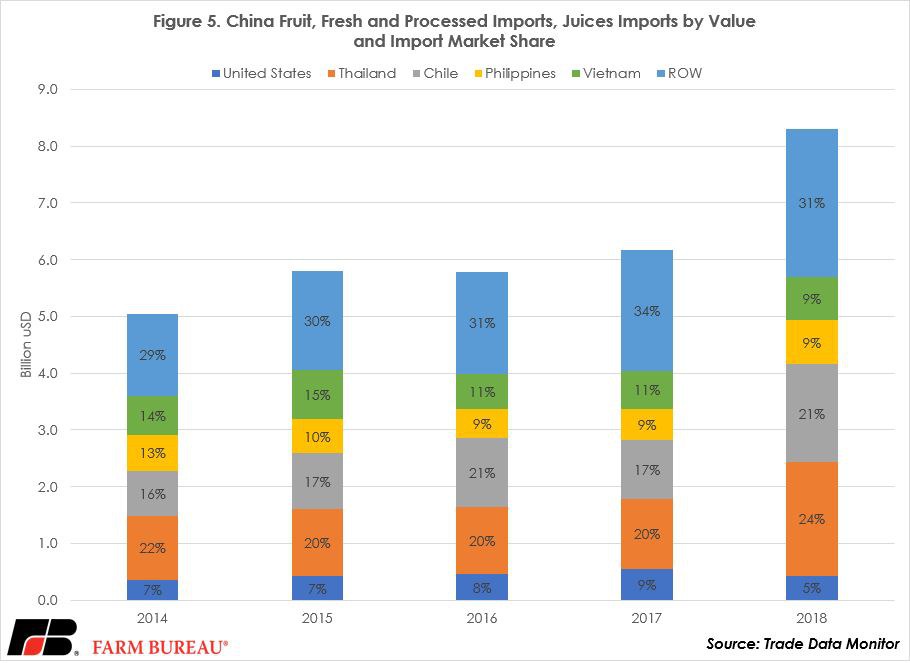

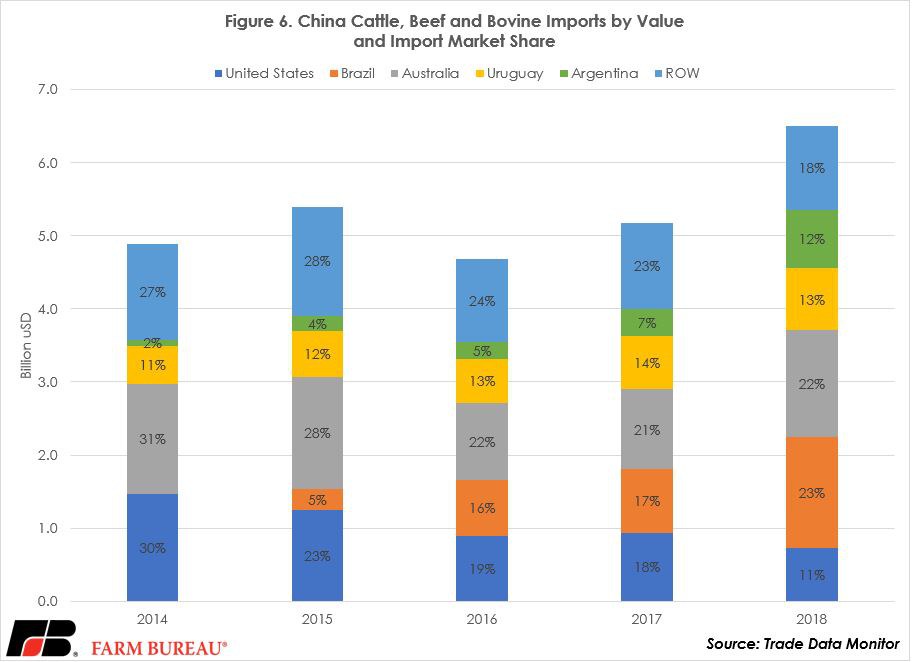

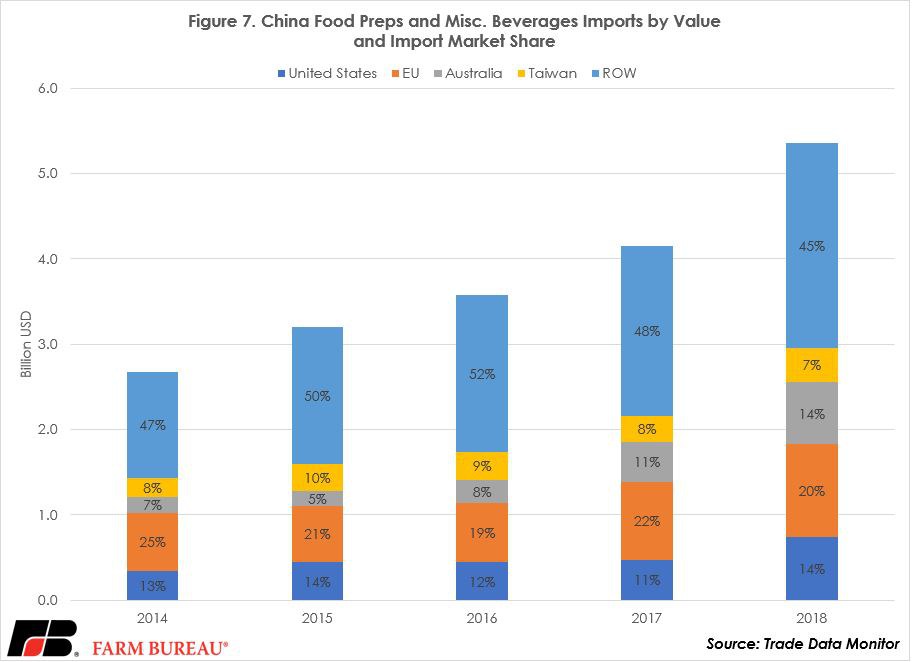

Breaking down China’s 2018 imports by product category in Figure 2 provides additional insight. Soybeans and soybean products totaled $38.5 billion in 2018 and accounted for 31% of total ag imports. By value, dairy products were the second-largest import category, with imports totaling nearly $10.8 billion and representing about 9% of total ag imports. The title of third most valuable import category belonged to fruit, which includes fresh and processed fruits as well as fruit juice. China imported $8.3 billion in fruit in 2018, accounting for 7% of total ag imports. Global imports of cattle, beef and bovine products were nearly $6.5 billion and accounted for 5% of China’s total ag imports in 2018. Rounding out the top five, prepared foods and miscellaneous beverages (which does not include alcoholic or fruit-based beverages) at $5.3 billion accounted for 4% of China’s total ag imports in 2018. Figure 2 provides global import values for 15 different import categories, plus an “other” category that includes all products not otherwise specified. (The HS6 codes which are included in each product category are defined by USDA Foreign Agricultural Service, following the World Trade Organization-Agricultural Total specification available via the General Agreement on Trade in Services database.)

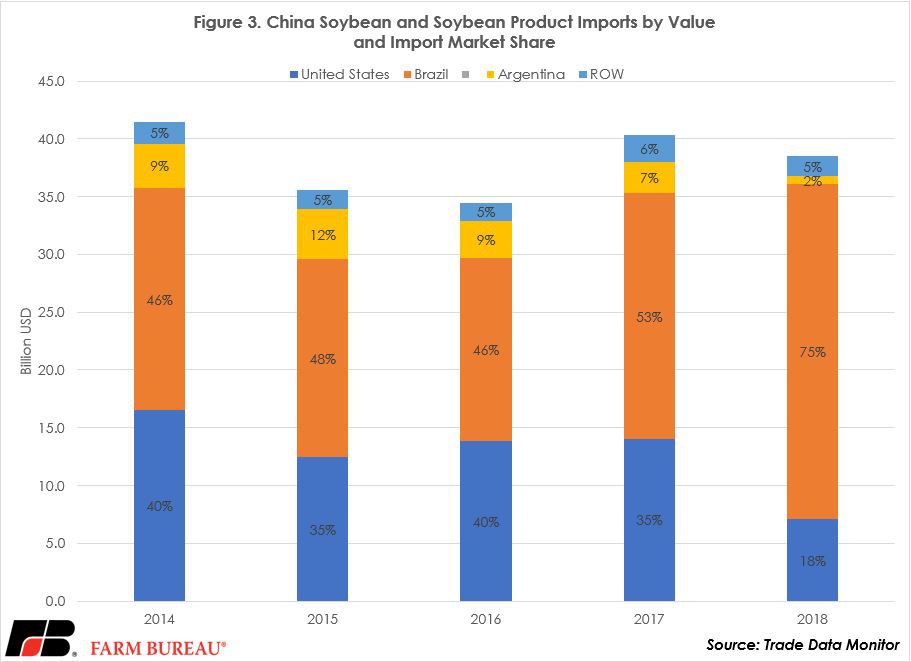

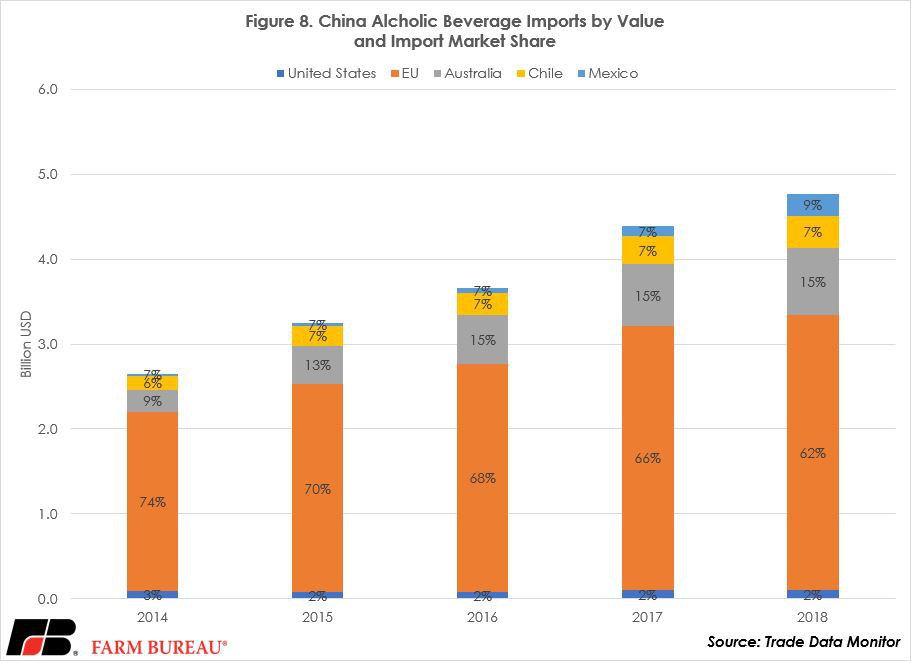

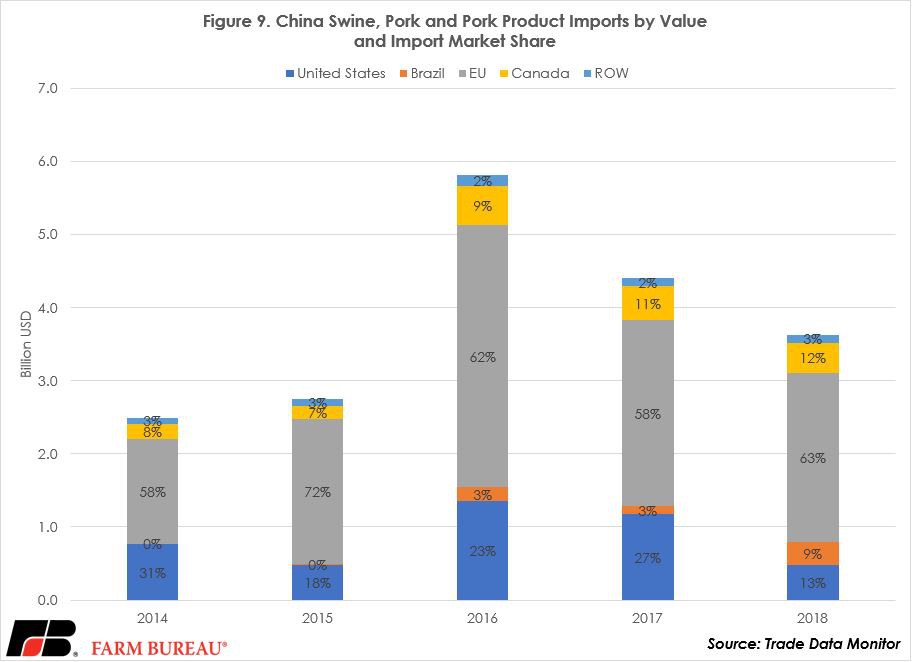

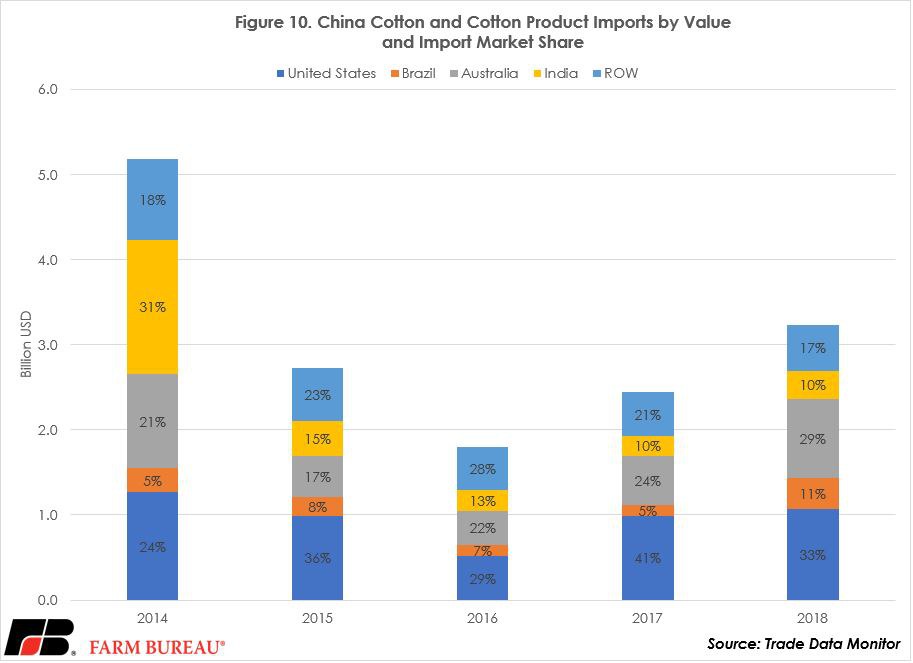

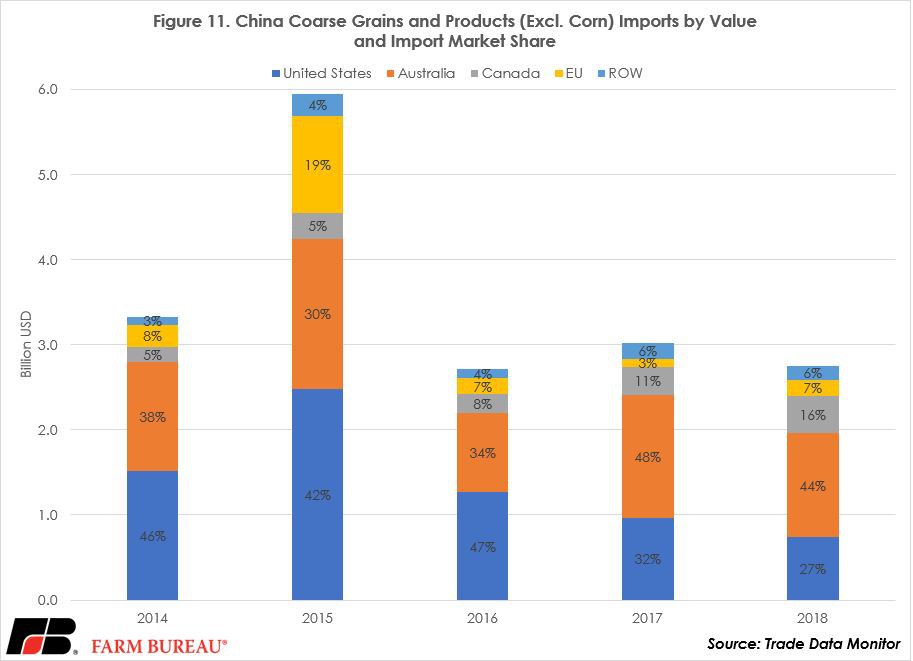

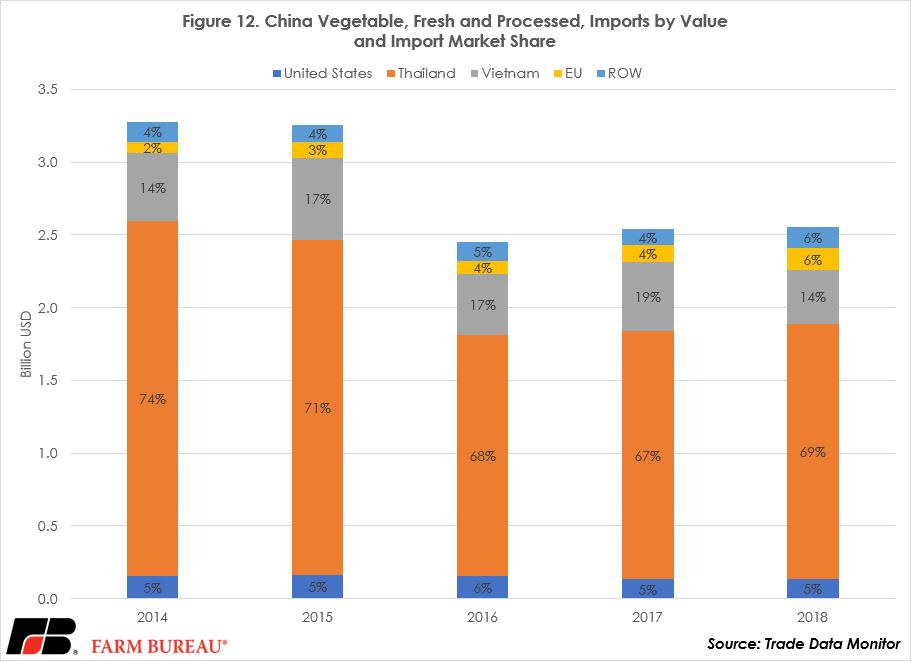

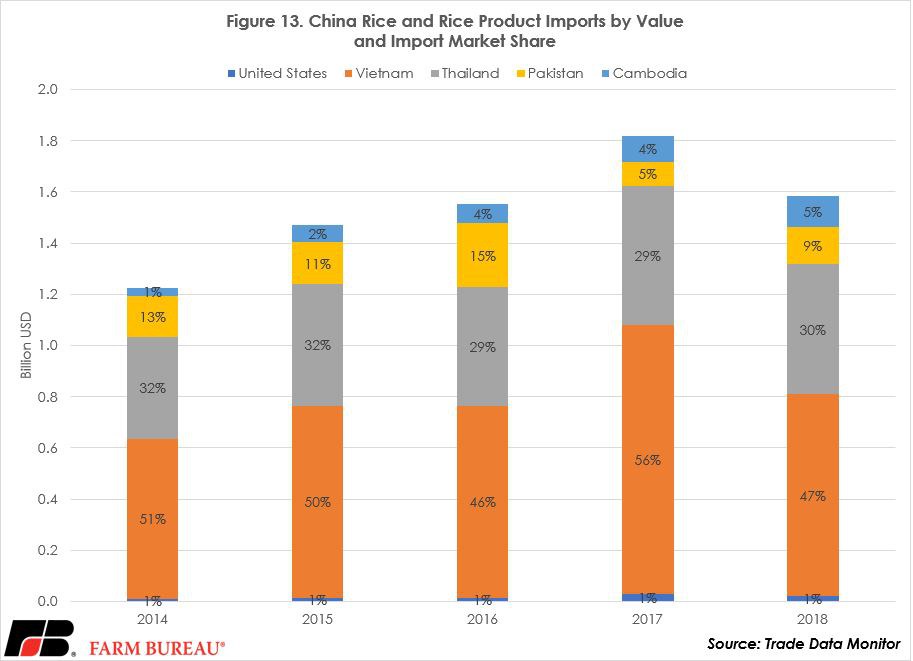

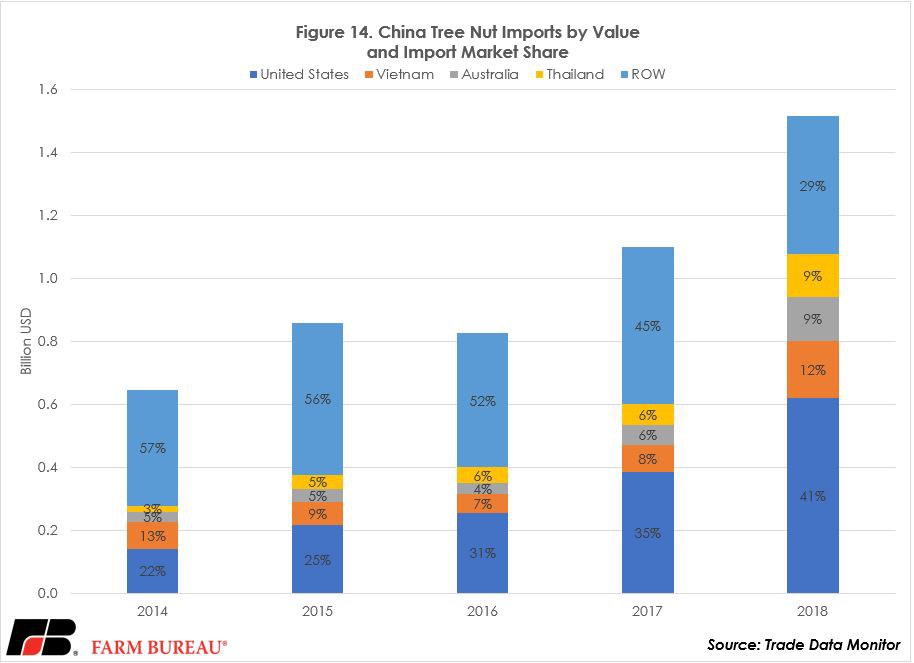

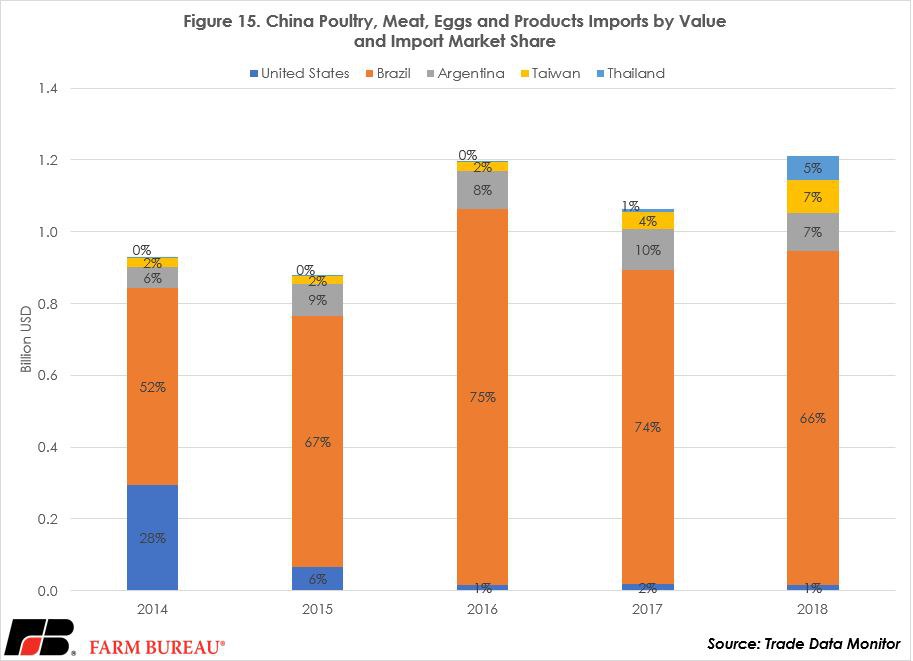

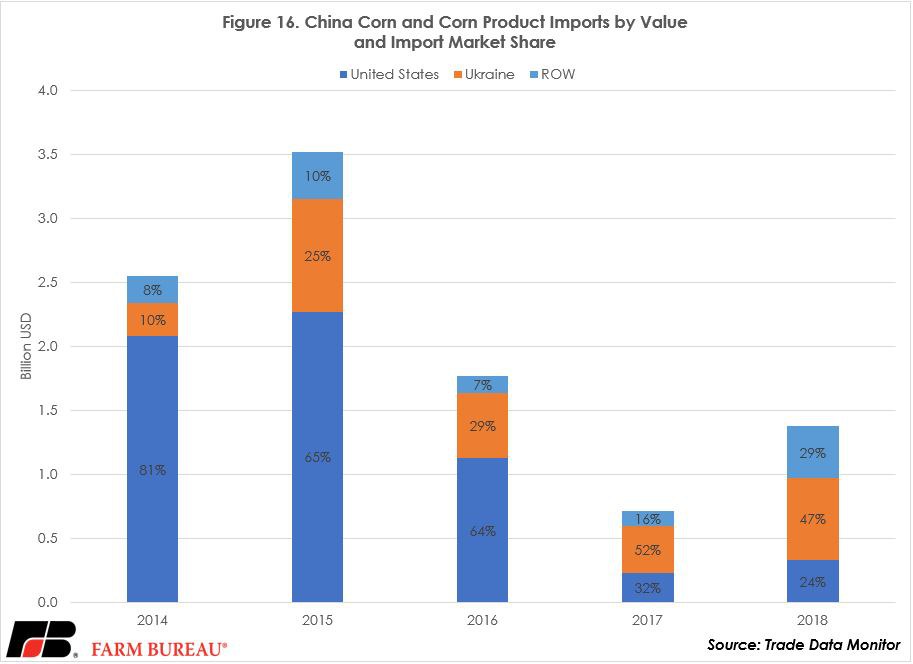

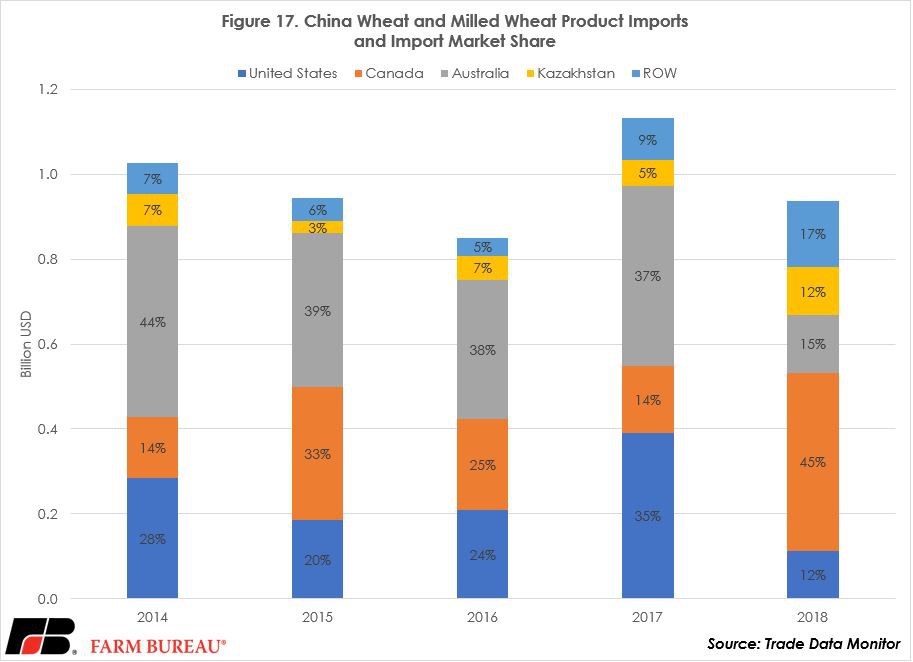

The USTR factsheet points out that “China and the United States recognize that purchases are to be made at market prices based on commercial considerations.” Between this language and the high-level view of China’s imports, it seems clear that the U.S. is going to have to work to reach $40 billion in ag exports. In order to achieve this level of ag exports, the U.S. will have to win market share away from other competitors and the product mix may be different from what the U.S. has exported in the past. Market share will be won on a product-by-product basis, with different competitors for each product. Figures 3-17, included at the end of the article, give some illumination of the total value of Chinese imports for all of the 15 different import categories that we included in Figure 2, as well as the market share for the top suppliers from 2014-2018.

Figures 3-17 highlight where Chinese ag imports have been, and which countries presented the most competition during that time. However, as we all know, things can change quickly and because China is such a large market those changes can significantly alter export opportunities. For example, Figure 9 demonstrates that Chinese imports of swine, pork and pork products by value peaked around $6 billion in 2016. But the outbreak of African Swine Fever in China in 2018 dramatically altered the country’s pork import landscape. According to Chinese customs data, China imported 2.108 million MT of pork in 2019, an increase of 75% from 2018 and 30.1% higher than 2016. So, while pork was the sixth-largest import category in 2018, it will likely be a larger share of China’s import mix in 2019, 2020 and 2021. The same can likely be said for beef and poultry. If China decides to make a push for ethanol inclusion, we should expect that the product category of corn and corn products (which includes ethanol) would rocket from its current position as the 14th-largest product category.

Summary

A lot can change in 24 months, but the potential to achieve average ag exports to China of $40 billion seems obtainable. What is certain is that the U.S. will have to fight for market share in order to achieve the export goal and the product mix may be different from what the U.S. has exported in the past.

Farm Bureau has been invited to participate in USDA’s 96th annual Agricultural Outlook Forum. Your participation in this short and informal survey will help Farm Bureau staff communicate the general sentiment of the industry and our membership on the health and outlook for the U.S. farm economy.

Take the survey now at www.fb.org/farmeconomy

Trending Topics

VIEW ALL