China Lowers Tariffs, but Catching Up is Hard to Do

TOPICS

Trade

photo credit: Getty

Veronica Nigh

Former AFBF Economist

Neil Sedaka sang that “Breaking up is hard to do,” but from an agricultural trade perspective, we would offer our version that catching up is hard to do when U.S. products face higher tariff levels than our global competitors. And our experience with trade agreements that we’re not party to shows us it’s true. The latest example comes from China, which recently announced a package of tariff cuts on a wide variety of food and consumer products. The welcome tariff reductions will impact about a dozen agricultural products that are of interest to the United States, and will hopefully help the U.S. regain market share lost to competitors that have free trade agreements with China, even if temporarily.

On Nov. 22, China’s Ministry of Finance announced that starting Dec. 1, 2017, the import duty on 145 consumer goods will be reduced by a tentative tax rate. The list of products is diverse and truly consumer-focused. Prior to these reductions, tariffs for products on the list ranged from 3 to 65 percent, with average and median tariffs of 17 and 15 percent, respectively. The reductions to take place are significant and range from 30 to 100 percent. The average tariff reduction is 56 percent and the median is 50 percent.

A few items on which tariffs will be reduced: air conditioners, medicines, some articles of clothing, blankets, waterproof footwear, refrigerators, freezers, washing machines, electric shavers, coffee makers and toasters. While not directly agricultural in nature, several of these items will allow Chinese consumers to store, utilize and benefit from U.S. food products, certainly a good thing in the long run, i.e. kitchen appliances.

In addition, the list also includes 33 food and fish items, of which eight items are products that the U.S. exports a significant amount of and another four items which the U.S. exports either intermittently or in a fairly small quantity. The eight products of most interest: HS 040620, grated or powdered cheese; HS 040630, processed cheese, not grated or powdered; HS 040640, blue-veined cheese, other-veined cheese; HS 040690, other cheese, not included in other HS codes; HS 08026190, macadamia nuts in-shell; HS 19011090, pre-packaged infant food (other than powdered formulas); HS 21069090, certain food preparations; and HS 220830, whiskies.

Cheeses (HS 040620, 040630, 040640, 040690)

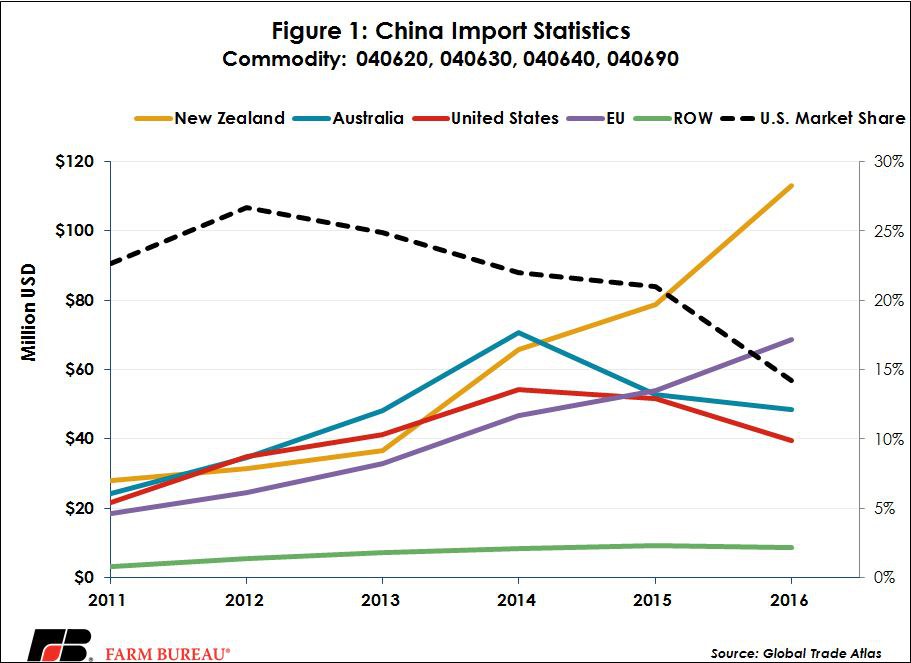

The United States has a significant presence in the Chinese cheese market. In 2016, the U.S. exported nearly $40 million in cheese within the covered HS codes. That $40 million represented a 14 percent share of the $278 million market. This is down from the peak market share of 27 percent achieved in 2012.

A number of things can influence market share, but in this case it would be hard to deny the contribution of competitors with premium access, i.e. lower tariffs, to the Chinese market. While the U.S. and other cheese exporters without FTAs have paid duties of 12 percent, exports from New Zealand and Australia have been paying reduced rates. For New Zealand, tariff reductions began in 2008, with HS040620 and HS040640 falling to zero in 2012 and 040630 and 040690 falling to zero this year. For Australia, tariff reductions began in 2015, fell to 6 percent (HS 040640) in 2017 and 8.4 percent (HS 040620, 040630, 040690) and will eventually be eliminated by 2019 (HS 040640) and 2024 (040620, 040630, 040690). Figure 1 clearly demonstrates the impact of this preferred access for New Zealand and the impact of the EU’s geographic indicators rules. The EU’s policies on geographic indicators dictate that only European Union cheesemakers be able to use common cheese names like parmesan, asiago and feta, limiting the ability of U.S. cheesemakers to rebrand familiar foods with unfamiliar names, limiting their sales potential. Beginning Dec. 1, cheese imports from the U.S. and other non-FTA partners will fall to 8 percent, down from 12 percent (HS 040620, 040630 and 040690) and 15 percent (HS 040690) as a result of China’s unilateral action.

Macadamia Nuts, in-shell (HS 08026190)

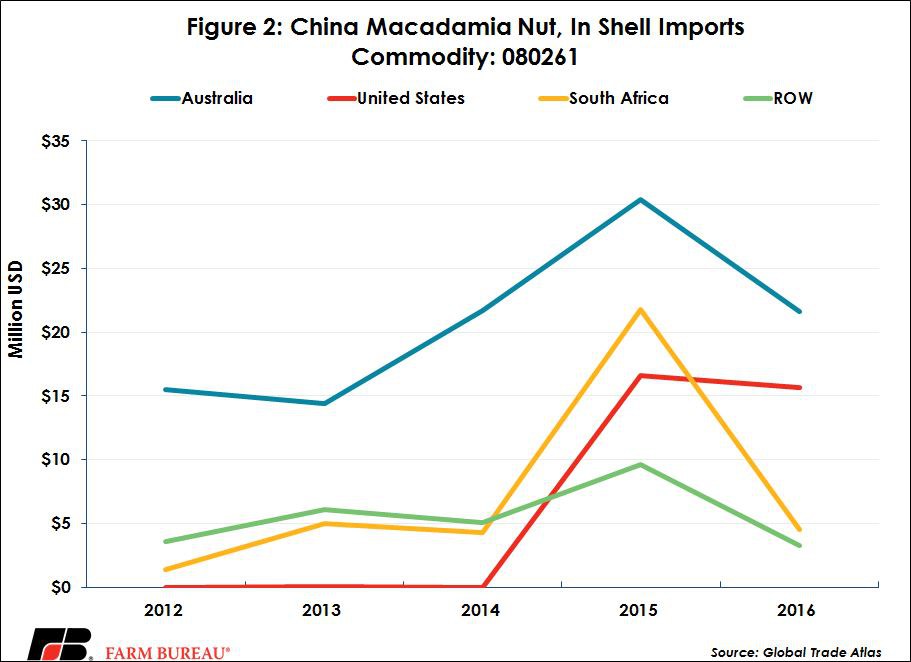

Grown in Hawaii, California and Florida, the U.S. is the world’s second largest producer of macadamias, topped by Australia, where the nut originated. Other key producers include South Africa, Guatemala, Costa Rica and Kenya. Australia dominated the Chinese market for one of the world’s most expensive nuts, until growers in the U.S., South Africa and Zimbabwe entered in 2015. And boy did the U.S. make its presence known. Between 2012 and 2014, the U.S. exported less than $100,000 of macadamia nuts combined. That number jumped to nearly $17 million in 2015 and $16 million in 2016. Despite significant tariffs, imports of all imported nuts such as almonds, pistachios, pecans, and macadamia nuts are surging as a result of rising incomes and enhanced consumer awareness about the nutritional attributes of nuts.

The tariff on in-shell macadamia nuts is significant at 24 percent. Of course, due to the Australia-China FTA, Australia pays less than its competitors for access in the Chinese market. Tariffs on Australian macadamia nuts began to fall in 2015, are 9.6 percent in 2017 and will fall to zero in 2019. For the U.S. beginning on Dec. 1, the tariff rate on non-FTA imports of in-shell macadamia nuts will fall to 12 percent, one-half of the current tariff level. While this is still below the 4.8 percent Australia nuts will face in 2018, it’s significantly more pleasant than 24 percent.

Temporary Tariff Measures

It is not uncommon for countries to offer temporary reductions in their tariffs in order to stimulate purchases. In fact, the United States has passed an annual piece of legislation known as the Miscellaneous Tariff Bill, which has a similar goal as the Chinese action. The MTB is designed to boost the competitiveness of U.S. manufacturers by lowering the cost of imported inputs without harming domestic firms that produce competing products.

In addition, in the case of finished goods, MTBs similarly reduce costs for consumers where there is no domestic production and thus no impact on domestic firms. Overall, the tariff relief contained in MTBs is designed both to be broadly available to any entity that imports and pays duties pursuant to the specified tariff heading and to benefit downstream producers, purchasers and consumers.

China’s action is certainly welcome, even if the tariff reductions are temporary. As Jaime Castaneda, U.S. Dairy Export Council senior vice president of trade policy, said in a statement:

"USDEC recognizes that the U.S. remains at a disadvantage not only in China but in other countries when it comes to tariffs due to lack of U.S. free trade agreements. We are committed to finding ways to recoup that competitive disadvantage."

Jaime Castaneda, U.S. Dairy Export Council Senior Vice President of Trade Policy

Lower tariffs, if only temporary, are a step in the right direction, but to paraphrase Mr. Sedaka’s well-known words, catching up is hard to do.

Trending Topics

VIEW ALL