China Continues to Drive Sorghum Acreage and Consumption

John Newton, Ph.D.

Former AFBF Economist

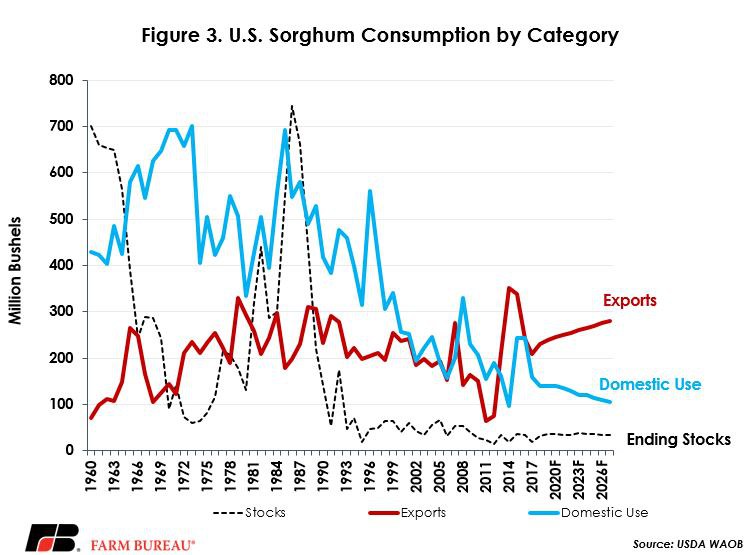

USDA’s February 2017 Agricultural Projections to 2027 projected for sorghum planted area to increase by nearly 1 million acres in 2018 to 6.7 million acres, an increase of 17 percent from 2017 levels. The catalyst for increased sorghum production has been increasing demand from China. For the 2017/18 marketing year sorghum exports are projected at 370 million bushels, nearly 60 percent of total use. The primary destination for these sorghum exports is expected to be China.

By 2027 USDA projects sorghum exports to represent more than 70 percent of sorghum consumption, dwarfing the second- and third-largest consumption categories of livestock feed and industrial use, i.e. ethanol. Nearly three-quarters of every sorghum acre harvested will be exported, and if Chinese purchasing trends continue, two-thirds of these acres will be destined for China.

When China started importing sorghum in 2013 it was due to three main factors: a tight corn market in China, restrictions on corn imports due to a tariff-rate quota and well-priced U.S. sorghum that resulted from a large crop.

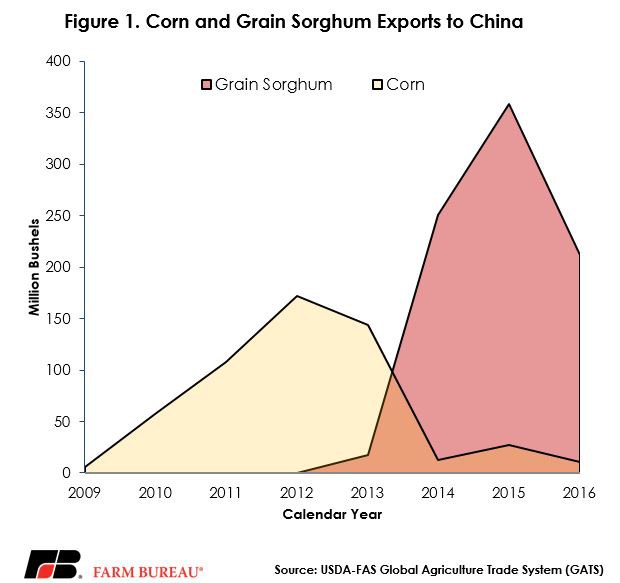

Another factor worth noting is that, unlike corn, sorghum does not have commercially viable genetically modified seed. Non-coincidentally, as China’s approvals of new corn (as well as soybean and cotton) traits slowed and began restricting trade, their imports of grain sorghum increased – offsetting and reducing the amount of corn imported from the U.S., Figure 1.

When sorghum imports began it was largely a result of Chinese policy decisions, however, the continued strength of U.S. exports suggests that Chinese buyers have come to view U.S. sorghum not just as a substitute product, but a valuable product in and of itself. For example, a variety of distilled alcoholic beverages consumed in China, such as baijiu, are made from fermented sorghum. The growing Chinese economy has resulted in increased alcohol consumption.

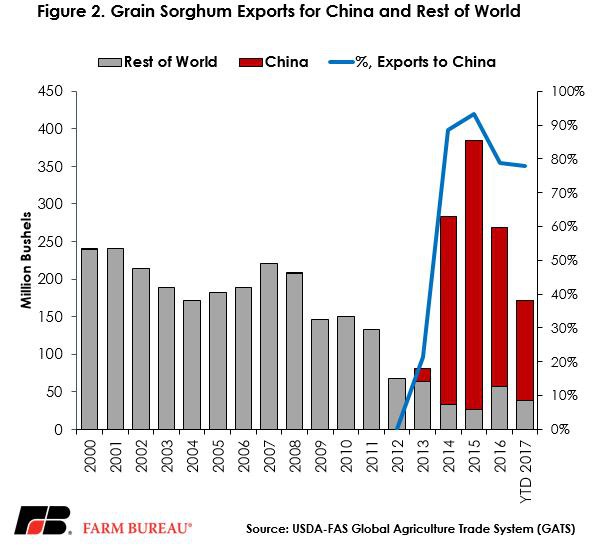

Since 2013, U.S. sorghum exports reached a high of 384 million bushels in 2015, and 93 percent of these exports went to China. While sorghum exports in 2016 and 2017 are lower than 2015’s record export volume, China continues to buy a large share of U.S.-produced sorghum, Figure 2.

Supporting USDA’s projection of expanded sorghum acreage in 2018, the October 2017 sorghum-to-corn cash price ratio in Kansas, a principal sorghum-producing region, reached the highest level since August 2015 at 0.93. In Texas, the ratio was as high as 1.06 in August 2017. Favorable price strength, combined with potential dryland yields, and lower costs of production per acre make sorghum an attractive planting alternative in some areas for 2018.

Implications

The impact of China on the sorghum complex mirrors that of soybeans, in that Chinese consumption has been a demand catalyst for sorghum. Other consumption categories, such as feed and residual use or ethanol continue to face headwinds. USDA projects for domestic consumption of sorghum to fall by 34 percent by 2027, Figure 3.

What’s at risk? Before China began buying sorghum in 2013, Mexico was the top customer of U.S. grain sorghum – buying more the 50 percent of U.S. sorghum exports. U.S. shipments to Mexico now represent less than 10 percent of U.S. sorghum exports. Abandoning the former top buyer, and putting all our eggs in the Chinese basket could roil sorghum markets should Chinese exports dissipate.

Insofar as China’s imports of sorghum continue, the decision to plant additional sorghum acres in 2018 may drive profit opportunities for some growers. However, given the sizable share of sorghum exports to China, expected returns from sorghum acres could not be as planned if Chinese demand weakens – as was the case in 2016 and 2017.

Trending Topics

VIEW ALL