Change on the Horizon for the Conservation Reserve Program?

photo credit: Amanda Kaiser, Used with Permission

John Newton, Ph.D.

Former AFBF Economist

Implications

The Conservation Reserve Program (CRP) is a voluntary program that pays U.S. farmers to retire environmentally sensitive cropland. Given recent lower commodity prices, for some growers, the option to retire lands through conservation programs may be viewed as an economic substitute for keeping the land in production. However, on May 3, 2017, USDA issued a notice that only high-priority lands identified at the state-level would be accepted for continuous enrollment in fiscal year 2017 (CRP-828).

Following requirements of the 2014 farm bill, no more than 24 million acres may be enrolled in CRP during the 2017 and 2018 fiscal years. Levels of enrollment near the legislative cap and a limited volume of acres expiring from the program led USDA to prioritize CRP conservation initiatives. Today’s article reviews CRP enrollment trends and the efforts to modify the program during the next farm bill.

What is the Conservation Reserve Program?

Land retirement programs provide federal payments to agricultural landowners for temporary changes in land use or management to achieve environmental benefits. The largest of these programs is CRP, a voluntary conservation program aimed at conserving soil, water and wildlife resources by removing highly erodible and environmentally sensitive lands from agricultural production and installing resource-conserving practices.

Contracts for land enrolled in CRP are 10 to 15 years in length. In exchange, USDA provides a yearly rental payment for removing these lands from production. For more information on USDA-sponsored conservation initiatives, including the CRP program, visit AFBF’s Farm Bill Resources Page.

Trends in CRP Enrollment

Congress introduced the Conservation Reserve Program in 1985. Due to a variety of economic factors, including a period of low commodity prices, high debt-to-asset ratios in the farm sector, and heightened levels of farm bankruptcies, retiring lands from production quickly became a viable economic alternative to farming.

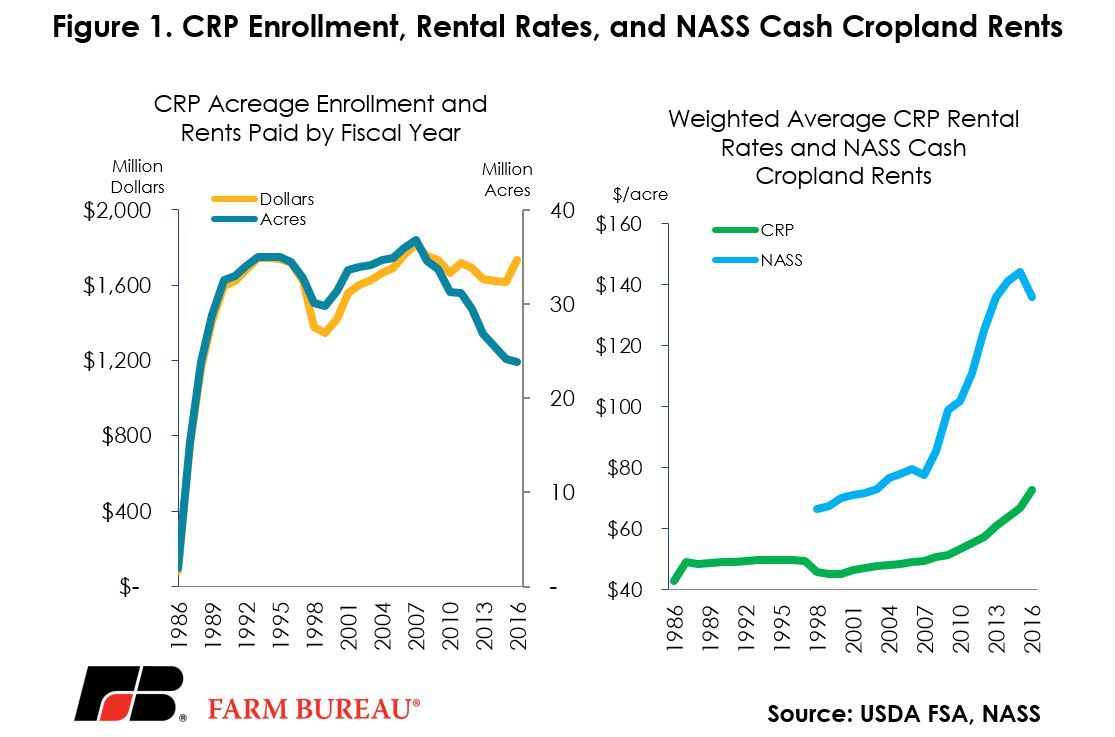

Enrollment in the CRP program climbed rapidly in the late 1980s. In 1987, 15 million acres were enrolled in CRP, and by 1990 more than 30 million acres were enrolled. Enrollment averaged 33 million acres from 1990 to 2012 and peaked at 36.8 million acres in 2007, Figure 1.

Over the last decade, however, acreage in CRP has declined. Each year more than a million acres have come out of retirement, and in total, CRP acreage has declined by 12.9 million acres. This decline in CRP acreage was in response to a variety of economic conditions in agriculture.

The trend toward higher commodity prices began in December 2006 and coincided with increased use of corn for ethanol production and higher export volumes of soybeans. Due to increased consumption and several years with below-trend crop yields, stock-to-use levels for key commodities declined to multi-year lows. Corn and soybean prices more than doubled from 2006 to 2012, and U.S. net farm income reached a record high in 2013.

Congress responded to these improved economic conditions by periodically lowering the maximum allowable acreage for CRP. The most recent farm bill reauthorized CRP and reduced the enrollment cap from 32 million acres to 24 million acres by the 2018 fiscal year. A 2015 analysis, Changing Landscape of Corn and Soybean Production and Potential Implications in 2015, reveals that many of these acres that came out of CRP over the last decade are likely to have moved back into active cropland production due to the higher economic returns.

CRP Enrollment for 2016

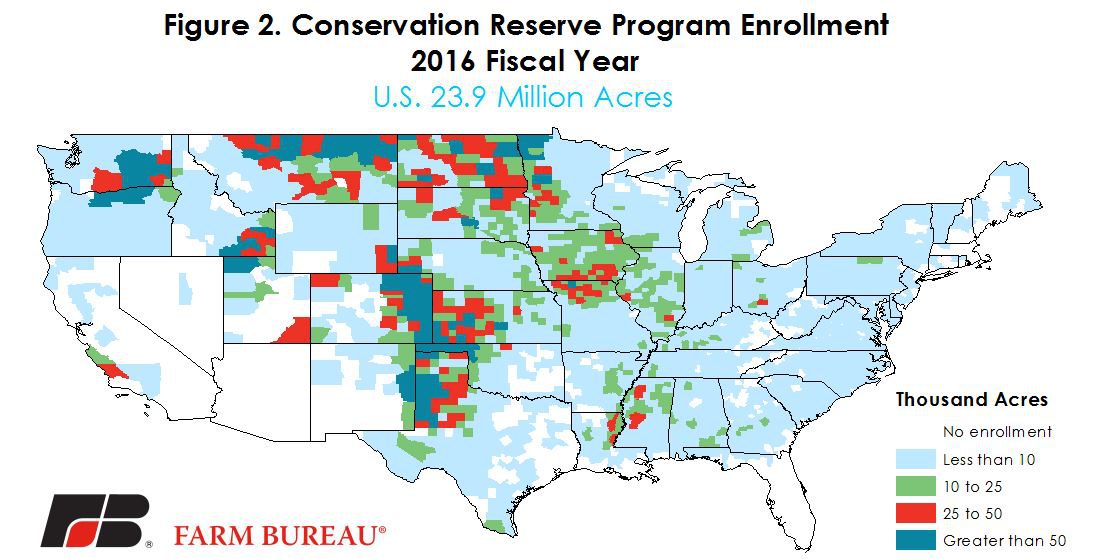

The U.S. has more than 360 million acres of cropland. Per the 2014 farm bill, maximum CRP enrollment for the 2016 fiscal year was 25 million acres. USDA’s Farm Service Agency’s CRP enrollment data reveals that for the 2016 fiscal year 23.9 million acres were enrolled in CRP, representing approximately 7 percent of U.S. cropland. More recent data reveals that 23.5 million acres were enrolled in CRP as of April 2017.

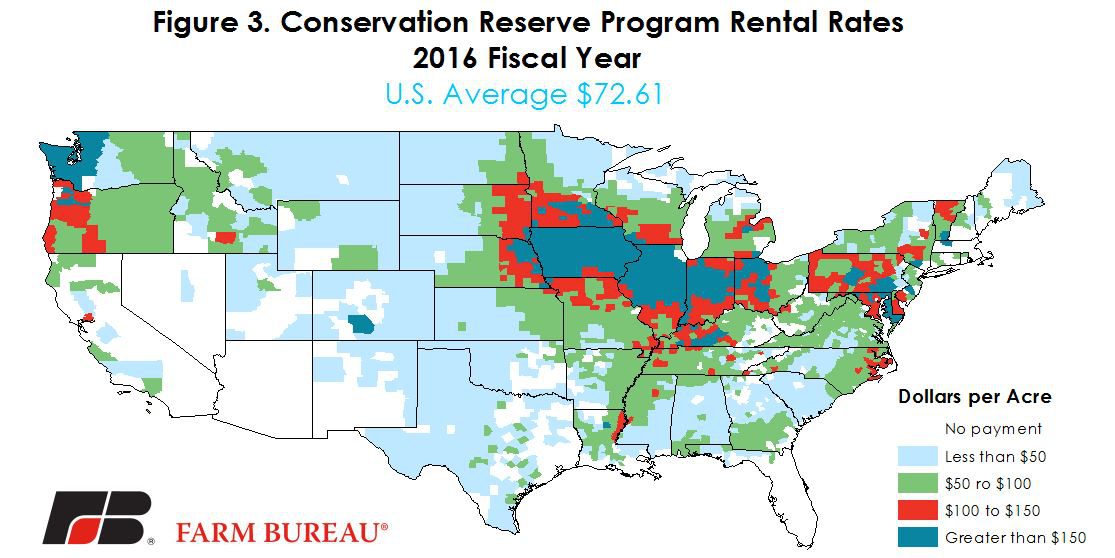

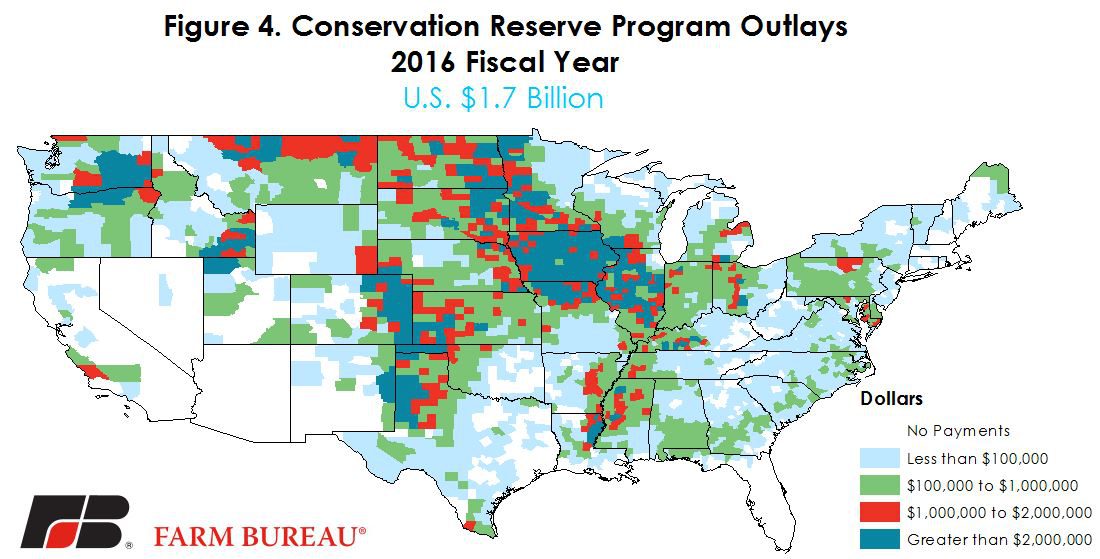

During the 2016 fiscal year, payments for CRP lands totaled $1.7 billion dollars and were at the highest level since the 2007 fiscal year. The average CRP rental rate was $72.61 per acre, up 9 percent from the 2015 fiscal year. By comparison, USDA’s Land Values and Cash Rents survey revealed the average cash rental rate for cropland in 2016 was down 6 percent from 2015 at $136 per acre. It is on the back of increasing CRP rental rates that outlays have increased, despite a reduction in enrolled acreage.

Most the CRP acreage is in the Upper Midwest and Southwest; however, CRP rental rates are higher in the Corn Belt. The net effect is that total CRP outlays are concentrated in the Southwest and Western Corn Belt. Figures 2 through 4 highlights the county-level distribution of CRP acreage, payments and rental rates.

Change on the Horizon?

As an option to reduce the deficit and cut spending, the Congressional Budget Office reviewed the implications of scaling back CRP acres (Limit Enrollment in the Department of Agriculture’s Conservation Programs). The option would prohibit new enrollment and re-enrollment in CRP but would not change the continuous enrollment option. CBO projected that limiting enrollment to only continuous CRP acres would reduce CRP enrollment by 10 million acres and would save $3 billion over 10 years.

With commodity prices well below recent highs, there is renewed discussion on moving the CRP cap in the other direction, i.e. to 30 million or 40 million acres. Just as limiting CRP enrollment has budget saving implications, increasing the cap would increase federal spending – potentially at the expense of other farm bill programs.

Currently, CBO's January 2017 Baseline estimates the 10-year cost of the CRP program at $20.6 billion, with an average rental rate of $78 dollars per acre in 2019 and rising to $91 dollars per acre by 2027. Increasing the CRP cap would most likely bring marginal acres, as opposed to highly productive cropland, back into the CRP program. Thus, using these CBO rental rates to estimate the cost of expanding CRP may upward bias the budget implications. For example, the average CRP rental rate in the top five states with the most acreage that’s come out of CRP since 2006 was $51.08 per acre for the 2016 fiscal year (Montana, North Dakota, Kansas, Texas and Minnesota).

Using this lower rental rate, and assuming annual rental rate increases used in the CBO projections of 1 to 2 percent, to increase the cap by 6 million acres could cost $3.4 billion over 10 years. Similarly, adding an additional 16 million acres (cap of 40 million acres) could cost $9 billion over 10 years, bringing the 10-year costs of the program to nearly $30 billion. The mechanics of the CRP program, e.g. rental rates or grazing opportunities, would need to be closely examined to offset the costs of adding additional acreage.

There are a variety of environmental and economic implications associated with modifying the CRP cap. A future Market Intel article will review the economic considerations. But, if current farm economics are the motivating factor for increasing CRP acreage, it’s important to consider that a de facto supply management program may not have the desired effect of lifting crop prices or farm income. In a global agricultural economy, acreage reductions in one market may send a market signal to add acreage in other markets. Thus, there is no guarantee that a higher CRP cap would increase commodity prices here in the U.S. for a prolonged period.

Trending Topics

VIEW ALL