Cattle Market Volatility Increasing Risk for Farmers, May Lead to Record Beef Prices

photo credit: Tia Nelson, Used with Permission

Bernt Nelson

Economist

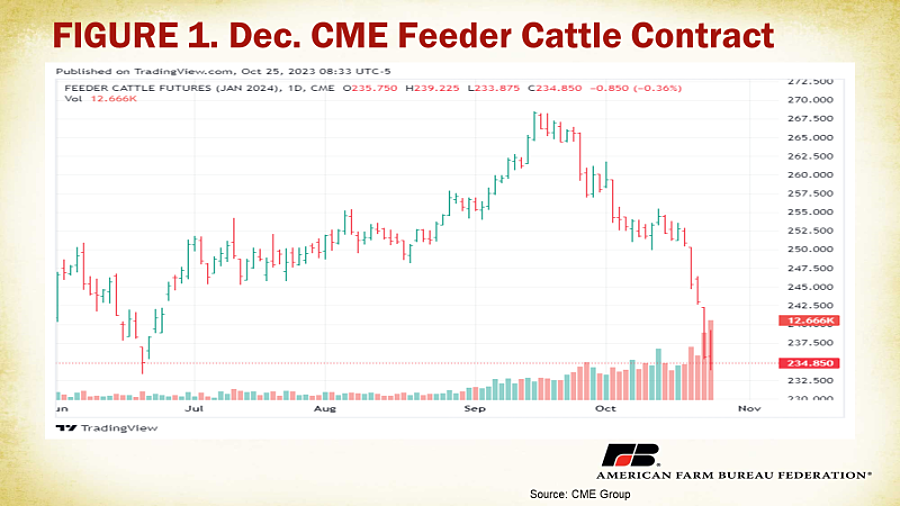

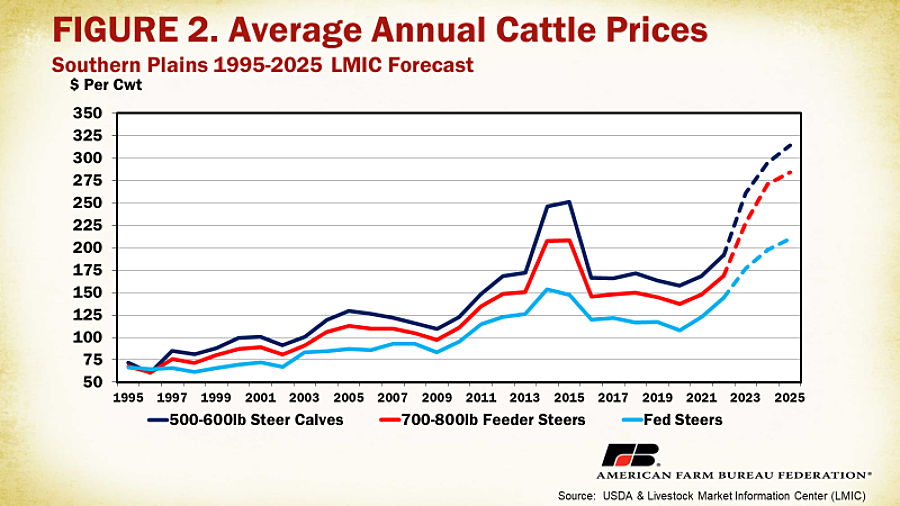

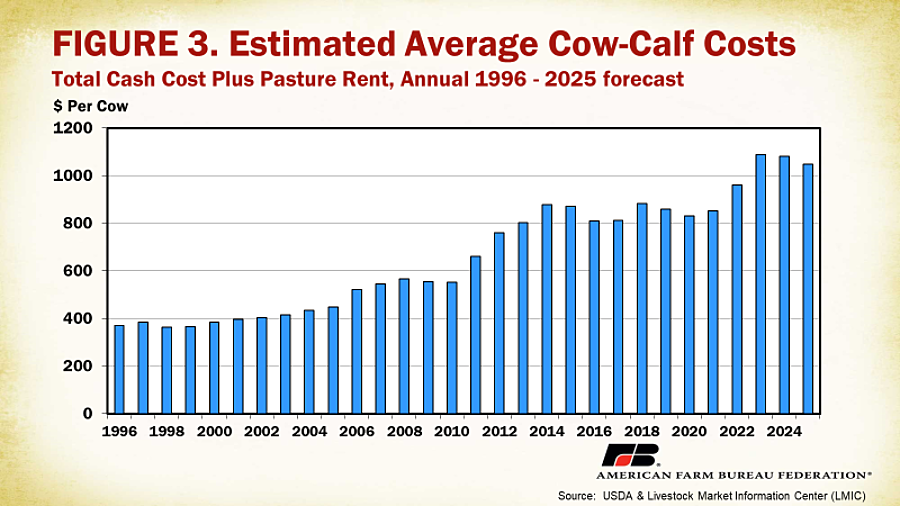

Between Oct. 18 and Oct. 23, six days after a bearish Cattle on Feed report, the January Feeder Cattle (Figure 1) contract fell 6.5%, from $252.86/cwt to $236.41/cwt, while December live cattle fell 4.4%, from $187.24/cwt to $178.92/cwt. In response to the dramatic drop in futures, this week packers have been buying cattle, which has kept cash prices strong. Cash prices for fed cattle were near $184/cwt in northern states such as Iowa and near $180/cwt in the southern Plains (Figure 2). Higher prices are providing opportunities for profitability in 2023, and tightening supplies should continue to keep cash prices strong through 2024 and 2025. But as the saying goes, “there’s no such thing as a free lunch.” Higher prices have come with higher inputs costs (Figure 3) and extreme market volatility that aren’t going away anytime soon. Volatility can be a good thing when it leads to higher prices in the short run, but too much can expose cattle producers to a higher level of risk. This Market Intel will examine the factors contributing to volatility in the cattle markets and its impacts on cattle farmers and consumers.

Cattle on Feed, Demand and The Cattle Cycle

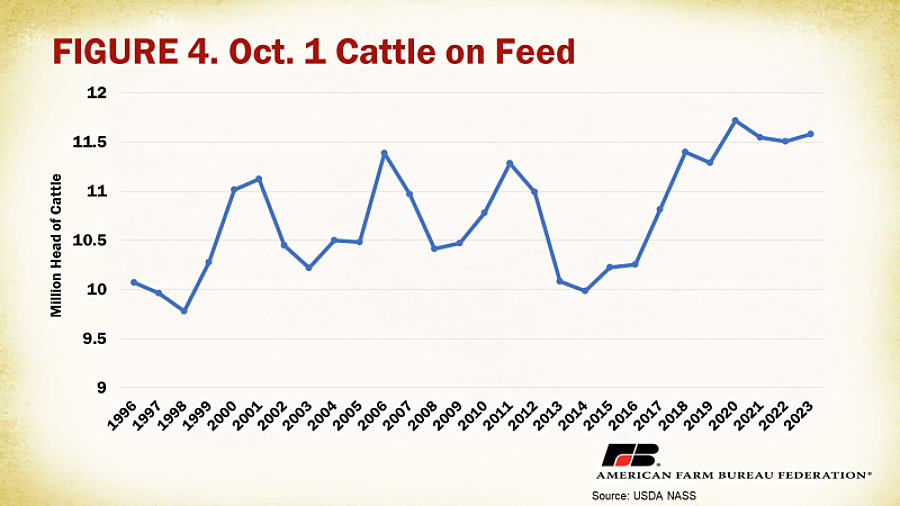

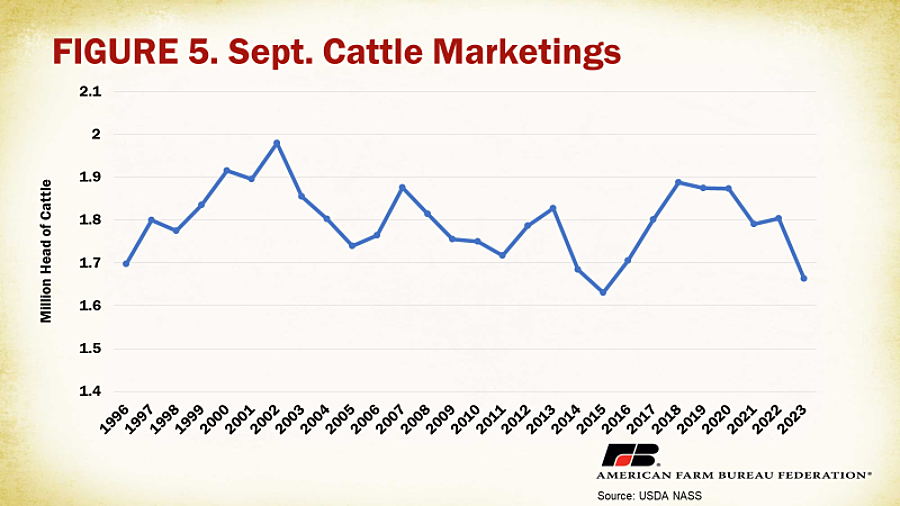

USDA released a bearish monthly Cattle on Feed report on Oct. 20, 2023, showing that cattle on feed (cattle being fed a ration and expected to be marketed for slaughter) on Oct. 1 totaled 11.58 million head. This is 1% higher than October 2022 and is the second-highest October Cattle on Feed total since the survey began in 1996 (Figure 4). Placements of cattle on feed in September were 2.21 million head, 6% greater than September 2022. Cattle marketed during the month of September were 1.66 million, 11% below 2022 and the survey’s second lowest ever (Figure 5).

The bearish news for cattle producers was higher total cattle on feed. This led to liquidation in the futures market. Higher calf and feeder prices are incentivizing placement of cattle into feedlots, making more cattle available for the market in the short run.

In the long run, the increase in cattle on feed means there are more cattle that are moving into the supply chain and thus removed from future inventory, as the cattle cycle continues its contraction phase. The cattle cycle refers to expansion and contraction in cattle inventory in response to farmer-perceived profitability. Each cycle typically lasts about 10 years. The current cattle cycle has been in a longer phase of contraction, driven by high input costs, drought and difficult profitability since 2018 – none of which is going away anytime soon.

Heifers on feed on October 1 totaled 4.6 million head, 1.3% greater than last October. The percentage of heifers being marketed is high and has held steady at near 40% of all cattle marketed. A high percentage of heifers going to market means fewer females available to rebuild the herd, and leaves the potential for a smaller calf crop in 2024. Replacement heifers (heifers held back for calf production) can be thought of as the planting intentions of the cattle business. Fewer heifers and cows available to produce calves indicate that the cattle inventory will continue to shrink, just as lower planting intentions for corn would indicate a smaller corn crop for the upcoming year. To expand again, female cattle will need to be retained for breeding rather than being placed on feed. When this happens, it will remove more cattle from the inventory available for beef production. This could easily drive beef prices to record highs in 2024 and 2025. The question is whether the U.S. economy, still facing the potential for a Federal Reserve-driven recession from interest rate hikes, can continue to support rising beef prices. If consumer spending begins to shift away from beef and toward less expensive substitutes such as chicken or pork, demand for beef will fall, putting downward pressure on cattle prices and making profitability challenging for farmers.

Volatility and Risk

Cattle farmers are exposed to more risk in cattle than most other agricultural markets because of the greater share of the consumer dollar they receive for their product. Consumer demand for beef responds more forcefully to changes in farm price received for cattle because the price received is such a large component of retail price. Ranchers receive approximately 39 cents of every dollar a consumer spends on beef. This is much higher than the average farmer share of every dollar spent on all food, which was 14.5 cents in 2021, according to a report by USDA’s Economic Research Service.

On May 31, 2023, the Chicago Mercantile Exchange (CME) set new trading limits for live cattle and feeder cattle futures contracts in accordance with their rule book. The adjustment nearly doubled the price trading limit from $0.0575 per pound to $0.10 per pound, allowing a trading range of about $10/cwt per contract to both the upside and downside. At first glance this might seem to increase risk exposure, but a deeper dive suggests the opposite.

Daily limits are used to help prevent panic buying or selling of a futures contract. Expanding the trading ranges of feeder cattle and live cattle futures allows for higher day-to-day market volatility. When a futures contract trades beyond the daily limit, it is said to be “limit locked,” which prevents participants from entering or exiting the contract, essentially trapping the contract owner. Increasing daily limits allows for greater volatility and allows more possibilities for traders to enter or exit the market when large swings occur.

So why is there so much volatility in the cattle market right now? Much like other commodities, volatility is closely tied to inventory. The low cattle inventory makes cattle markets especially sensitive to any changes in market conditions such as drought and exports, which is leading to higher volatility.

Trade can have a lot of influence on market volatility. The U.S. exported $11.7 billion in beef and beef products in 2022. More trade partners reduce market volatility because a diverse customer base encourages natural competition in the market. Trade partners can become a source of volatility if they control too much market share. For example, more than 60% of beef exports went to South Korea ($2.7 billion, 23%), Japan ($2.3 billion, 20%) and China ($2.1 billion, 18%). An additional $748 million, or 6% of exports, went to Taiwan. So, while Taiwan is still the sixth-largest export destination for U.S. beef and certainly important, if something were to happen that would disrupt that market it would create less volatility than if something were to happen to the South Korean market. (Data source: USDA-Global Agricultural Trade System)

Higher market volatility can mean better prices in the short run, but what about the long run? What does this mean for the potential for the cattle inventory to expand again? The average age of a farmer or rancher is going up. In fact, according to USDA’s 2017 Ag Census, it increased by 1.2 years since the 2012 census to 57.5. These farmers have an average of 21.3 years of experience on their current farm. Aging farmers have less incentive to invest in expansion again with so many obstacles to profitability, including increased exposure to risk.

The median interest rate on non-real estate loans has doubled since the beginning of 2021. Half of all new operating loans in the second quarter of 2023 had interest rates above 8.5%. When interest rates go up, banks require more collateral. The securable loan amount goes down when prices are falling, eating into farmers’ working capital (money used for day-to-day operation) and reducing the amount of money a farmer can borrow next year. The high cost of borrowing money is both an obstacle to existing farmers and a barrier to entry for newcomers that could help increase the cattle inventory.

Drought

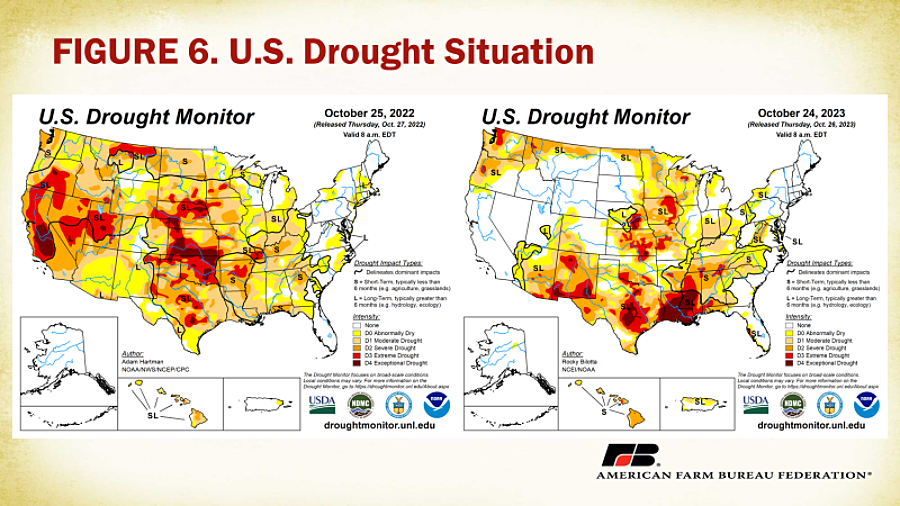

Drought is another major risk factor, driving up production costs and limiting access to grass, hay and other feedstocks. The top 10 cattle-producing states in the country are home to 57% of all beef cattle in the United States, with the top five states (Texas, Oklahoma, Missouri, Nebraska and South Dakota) containing nearly 40% of all U.S. beef cattle. All of the top five states have experienced severe drought in 2022 and 2023, with several of the top 10 experiencing the same (Figure 6). Rather than facing the prospect of damaged pastures and high input costs, many cattle farmers have continued to liquidate cattle, which will continue to hold the cattle industry in the contraction phase of the cattle cycle.

Summary and Conclusions

Cattle prices are up in 2023, but high market volatility and drought continue to push cattle farmers toward herd liquidation. Many American cattle farmers are at a crossroads and will have to decide whether to continue, downsize or to get out altogether. If the decision is to continue, they will face obstacles like market volatility, high input costs, potential economic recession and drought. Newcomers wanting to get started will face barriers to entry, requiring substantial working capital, in addition to the obstacles discussed in this article. Beef prices will approach record levels in 2024 and 2025. What happens to prices after that will largely depend on cattle farmers’ decisions to expand. Expansion in cattle inventory will need to happen before beef prices can come back down for consumers. The cattle business will need to provide profitable incentives to cattle farmers in order for it to make sense for them to grow the cattle herd again.

Trending Topics

VIEW ALL