Cattle Inventory Indicates Potential Expansion in the Dairy Sector

TOPICS

LivestockAFBF Staff

photo credit: Alabama Farmers Federation, Used with Permission

The recently released Jan. 1 Cattle Inventory report kicks off the year with hard numbers on both the dairy and beef cattle herd. This highly anticipated report is one of the few that looks at both total beef cattle and replacement numbers. For the dairy herd, monthly numbers are provided as part of USDA’s National Agricultural Statistics Service monthly Milk Production report. The Jan. 1 Cattle report is the only report that counts the dairy heifer replacements held for breeding.

The dairy herd inventory was up 1 percent during 2017, adding 54,000 head to last year’s Jan. 1number. It is the highest inventory on Jan. 1 since 1996. Milk cow replacements also increased 27,000 head from last year. This is also the fourth consecutive year dairy replacements represent over 50 percent of the milking herd, continuing the long-term trend of growing replacement numbers, which have become a larger and larger proportion of the dairy herd since 2004. Some attribute this growth to increased use of sexed semen and greater emphasis on reproductive management.

USDA’s World Agricultural Supply and Demand Estimates puts dairy prices lower heading into 2018, and yet the trend continues to keep ample supplies of heifers. Since 2014 all milk prices have been below $18 per hundredweight 30 out of the last 36 months. In 2016, dairy prices fell to $14.50, the lowest price since 2009.

The Jan. 1 inventory number is a point estimate and so only takes into account decisions made leading up to the inventory levels on that specific date. Unlike the beef herd, dairy herds rely on a continuous calving season to keep milk flowing all year. So decisions on when to breed cattle, add or remove cows from the herd are made on an ongoing basis. The replacement number is only given once a year and is reflective of the farmer’s decisions at that moment in time. With three years’ worth of lower milk prices, farmers are likely filling barns to spread debt loads across more animals. Any infrastructure changes made in high times, such as building new barns or updating new parlors came with additional debt-to-service, and maximizing these facilities can help a farm endure tough times. Another factor is fourth-quarter milk prices over the last three years, which have averaged higher than the annual average, making it an opportune time to make purchases ahead of the cattle report.

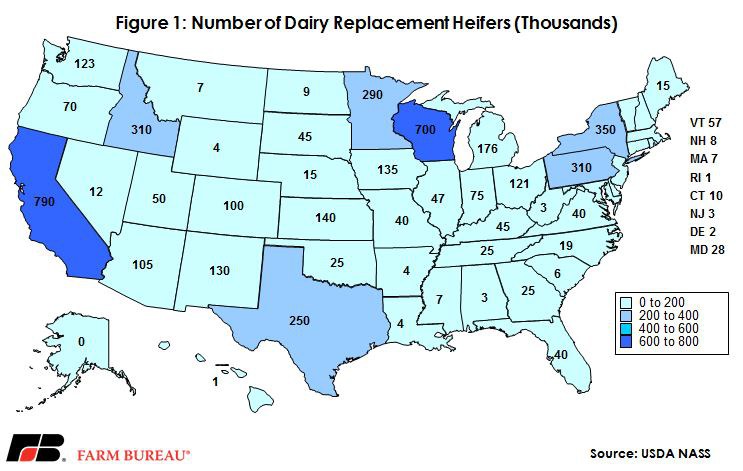

Figure 1 shows the number of replacement heifers by state on Jan. 1. Most states have fewer than 200,000 replacement animals and a handful have between 200,000 and 400,000. California and Wisconsin each had over 700,000 replacement heifers on hand heading into 2018. This is unsurprising coming from the first- and second-largest dairy states in the country, respectively. California reported a dairy herd size of 1.7 million animals, followed by Wisconsin at 1.3 million. The next largest state was New York with only 625,000 cows, followed by Idaho with 600,000 and Pennsylvania with 525,000 to start the year.

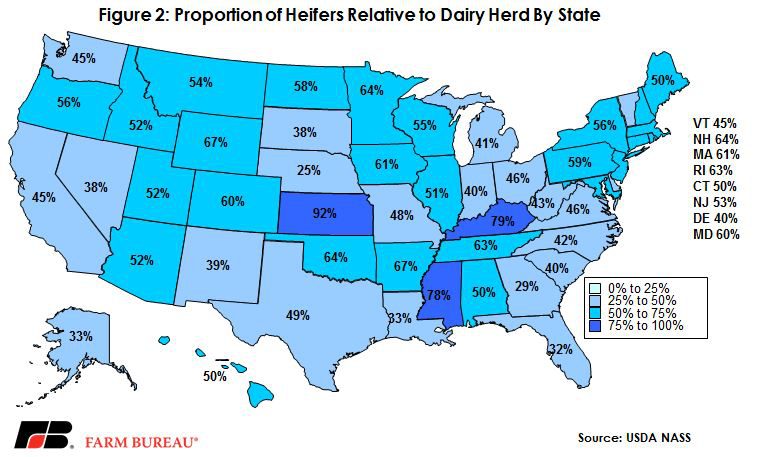

What’s more interesting is the proportion of heifers held in states relative to the number of cows in those states. Figure 2 shows the ratio of heifers to cows for each state. Half the states are at or below 50 percent in retaining heifers. Other states have well over that proportion. This could indicate areas where expansion will take place or it could be areas with high concentrations of heifer-raising facilities. Kansas, Kentucky, and Mississippi stand out as having an exceptionally high number of heifers based on the number of milk cows in the state.

The Kansas dairy herd has grown 16 percent in the last five years, while the number of heifers has increased 40 percent. However, the Sunflower State also has quite a few heifer-raising facilities that ship heifers out of state. Mississippi and Kentucky have seen declining dairy numbers to the tune of 36 and 21 percent, respectively, while the number of heifers has declined over the last five years. Kansas is expecting to continue expanding its dairy herd along with states such as Minnesota, Colorado, Oregon and New York. All these states have above-average heifer ratios and have been expanding the number of replacements over the last five years, as well as increasing the number of milking cows, with the exception of Minnesota.

Trending Topics

VIEW ALL