Cattle and Hog Market Disruptions Renew Interest in Mandatory Country of Origin Labeling

TOPICS

Trade

photo credit: Colorado Farm Bureau, Used with Permission

Veronica Nigh

Former AFBF Economist

Major disruptions in the cattle and hog markets, one of the several fallouts of the COVID-19 pandemic, have led to many conversations about policy options that might be helpful. One much-discussed solution is mandatory country of origin labeling.

Live Cattle and Pig Trade

Before diving into the background on MCOOL it is helpful to understand the interconnectedness of the live cattle and live hog markets in the United States, Canada and Mexico. Over more than two decades, the cattle and hog industries in Canada, the U.S. and Mexico have evolved based on a consistent and favorable market arrangement. Nearly 100% of U.S. live cattle imports come from Canada and Mexico and nearly 100% all live hog imports come from Canada. To learn more about how these marketing channels developed, check out these Market Intel articles on beef and pork trade.

Background

MCOOL provisions were enacted in the 2002 farm bill to take effect on Sept. 30, 2004. After several delays, the final implementation rule took effect on March 16, 2009. The MCOOL rule required most retail food stores to inform consumers about the country of origin of fresh fruits and vegetables, fish, shellfish, peanuts, pecans, macadamia nuts, ginseng, and ground and muscle cuts of beef, pork, lamb, chicken and goat.

Before the MCOOL provisions went into effect, Canada and Mexico held consultations with the United States. Despite these consultations, the U.S., Canada and Mexico were unable to resolve their differences, resulting in Canada and Mexico requesting the establishment of a WTO dispute settlement panel in October 2009.

The WTO DS panel in November 2011 concluded that some features of U.S. MCOOL discriminated against foreign livestock and were not consistent with the U.S.’s WTO obligations. The U.S., Canada and Mexico all appealed the panel’s finding, but ultimately the United States was left with a compliance deadline of May 23, 2013. In order to meet the deadline, USDA issued a revised MCOOL rule requiring that labels show where each production step (born, raised, slaughtered) occurred and prohibited the commingling of muscle-cut meat from different origins.

Despite the labeling changes, Canada and Mexico still found MCOOL to be discriminatory against foreign cattle and hogs, as did a WTO compliance panel. A U.S. appeal of the compliance panel report proved unsuccessful, leading Canada and Mexico to request arbitration proceedings. In December 2015, the arbitration panel granted a retaliation level for Canada at CA$1.055 billion (US$781 million) and for Mexico at US$228 million. Following this finding, on Dec. 18, 2015, the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2016 repealed MCOOL for muscle cuts of beef and pork and ground beef and pork. After the repeal by Congress, USDA halted enforcement of MCOOL for beef and pork. Finally, on March 2, 2016, USDA amended the MCOOL regulations to reflect the repeal of the MCOOL law for muscle cuts of beef and pork, and ground beef and pork.

The Meat of the Problem

The MCOOL law prohibited USDA from using a mandatory animal identification system, but the original 2002 version stated that the Agriculture secretary “may require that any person that prepares, stores, handles, or distributes a covered commodity for retail sale maintain a verifiable recordkeeping audit trail that will permit the secretary to verify compliance.” Verification immediately became one of the most contentious issues, particularly for livestock producers, in part because of the potential complications and costs of tracking animals and their products from birth through retail sale.

The meat labeling requirements in MCOOL proved to be among the most complex and controversial of rulemakings, in large part because of the steps that U.S. feeding operations and packing plants had to adopt to segregate, hold and slaughter foreign-origin livestock.

The WTO panel found that MCOOL’s legitimacy was undermined because a large amount of beef and pork was exempt, putting imported livestock at a competitive disadvantage to domestic livestock for no reason. The panel noted between 57.7% and 66.7% of beef and 83.5% and 84.1% of pork did not provide origin information to consumers.

MCOOL had a number of statutory and regulatory exemptions that resulted in a significant share of beef and pork that did not convey origin information to consumers. Chiefly, MCOOL:

- exempted items from labeling requirements if they were an ingredient in a processed food;

- covered only those retailers that annually purchase at least $230,000 of perishable agricultural commodities; and

- exempted restaurants, cafeterias, bars and similar facilities that prepare and sell foods to the public from these labeling requirements.

Economic Impact of MCOOL

The 2014 farm bill required USDA to quantify the market impacts of MCOOL. The department assigned the research to a team of agricultural economists from Kansas State University and the University of Missouri. The report, released in 2015, found no evidence of meat demand increases for MCOOL-covered products, but found considerable evidence of increased compliance costs. Ultimately, the report found that MCOOL cost the meat industry and consumers billions.

By the Numbers

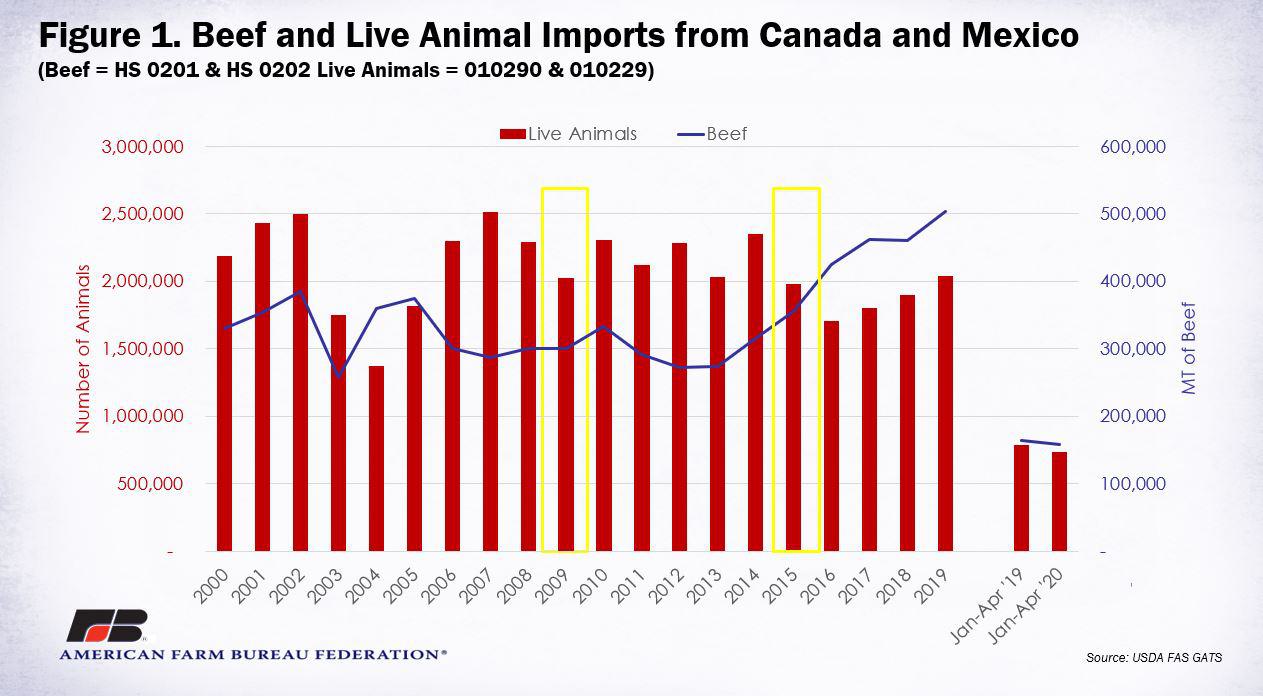

Figure 1 tracks calendar year live cattle and beef imports to the U.S. from 2000-2019 and January through April 2019 and January through April 2020. The years during which MCOOL was in effect, 2009-2015, are highlighted in yellow. Figure 1 demonstrates that imports of both non-breeding stock cattle and beef imports remained fairly steady throughout the MCOOL period. January through April 2020, live cattle imports from Mexico and Canada were down 7%, compared to the same period in 2019. January through April 2020, beef imports from Mexico and Canada were down 4%, compared to the same period in 2019.

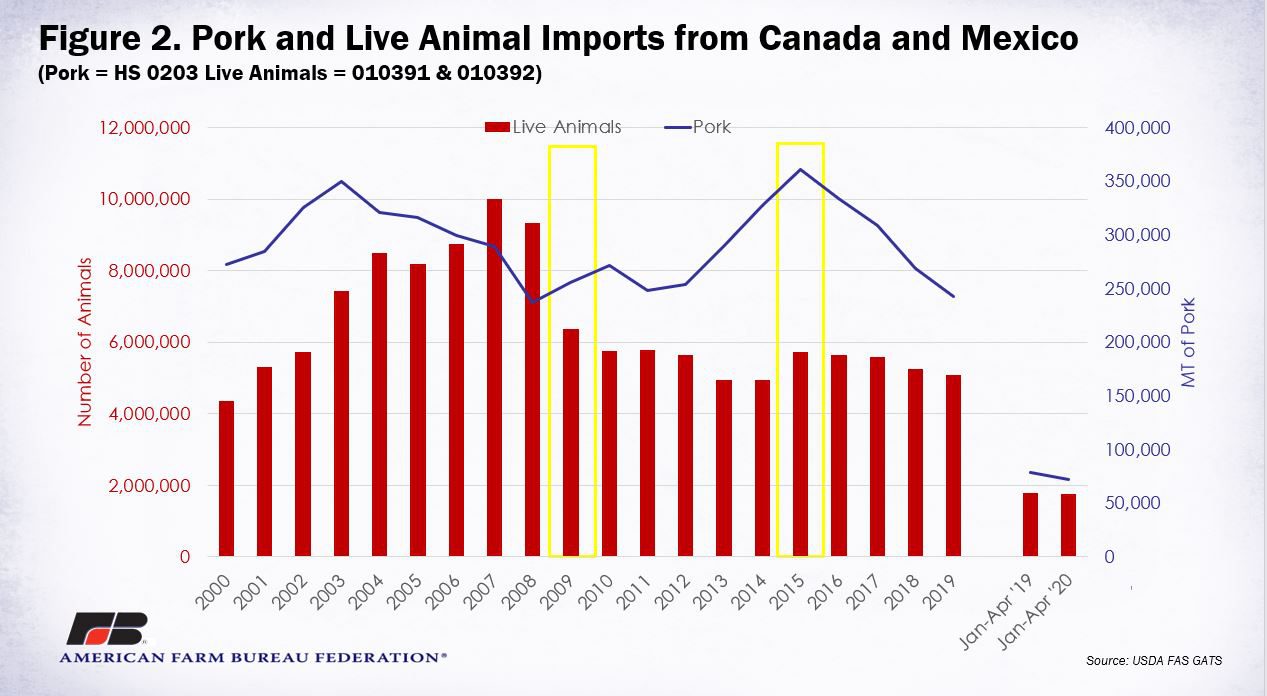

Figure 2 tracks calendar year live pig and pork imports to the U.S. from 2000-2019 and January through April 2019 and January through April 2020. Again, the years during which MCOOL was in effect, 2009-2015, are highlighted in yellow. Figure 2 demonstrates that while imports of live pigs fell considerably, pork imports rose considerably throughout the MCOOL period. In January through April 2020, live pig imports from Canada were down 1%, compared to the same period in 2019. In January through April 2020, pork imports from Canada were down 8%, compared to the same period in 2019.

MCOOL Beyond Beef and Pork

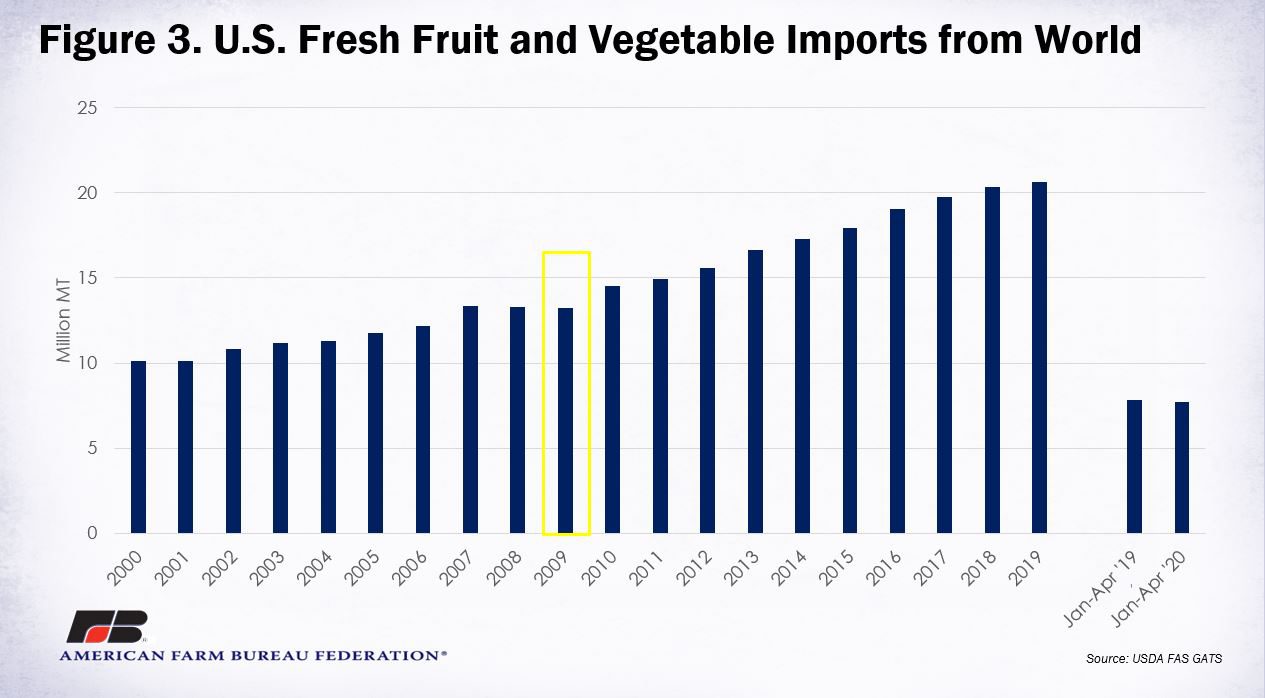

While repealed for muscle cuts of beef and pork and ground beef and pork in 2016, MCOOL remains in place for fresh fruits and vegetables, fish, shellfish, peanuts, pecans, macadamia nuts, ginseng, and ground and muscle cuts of lamb, chicken and goat. Despite the hope that MCOOL would make consumers more likely to purchase U.S.-produced goods, trade data suggests that consumer demand for imported goods remains high. For example, imports of fresh fruits and vegetables were 56% higher in 2019 than 2009, despite a strong U.S. industry and increasing “buy local” trends.

Summary

This has been an incredibly challenging year for producers around the country. As of June 8, USDA’s Farm Service Agency had received over 169,000 applications for the Coronavirus Food Assistance Program in the 13 days since the application period opened on May 26. Representing more than 54% of the total applications, nearly 92,000 are from livestock producers (livestock includes cattle, hogs and sheep (lambs and yearlings only)). This is a strong indication of the dire pain felt across the livestock sector. As we look for ways to ease that pain, it is not surprising we discuss a wide variety of policy tools, including those, like MCOOL, that have been tried before.

Trending Topics

VIEW ALL