Assessing Western Drought Conditions – Idaho Farmers Report Reduced Yields Under Dire Conditions

TOPICS

StillFarming

photo credit: Nancy Caywood, used with permission.

Daniel Munch

Economist

This is part three in a Market Intel series showcasing the impacts of drought conditions in the Western U. S. Part one presented the first set of results from AFBF’s Assessing Western Drought survey. This iteration from Idaho Farm Bureau illustrates state-specific hardships faced by farm and ranch families in the region.

Submission by: Braden Jensen, Deputy Director of Government Affairs, National Affairs Coordinator, Idaho Farm Bureau

Idaho is no stranger to dry conditions. In fact, the average annual precipitation for much of the state’s most populous and productive lands is less than 12 inches. This year has been especially dry and hot, with hydrologists recording average rainfall at just under 4.4 inches, putting more pressure on an already limited resource. Even areas of the state – primarily up north – that commonly receive significantly more rainfall than southern portions of the state are experiencing exceptionally dry conditions.

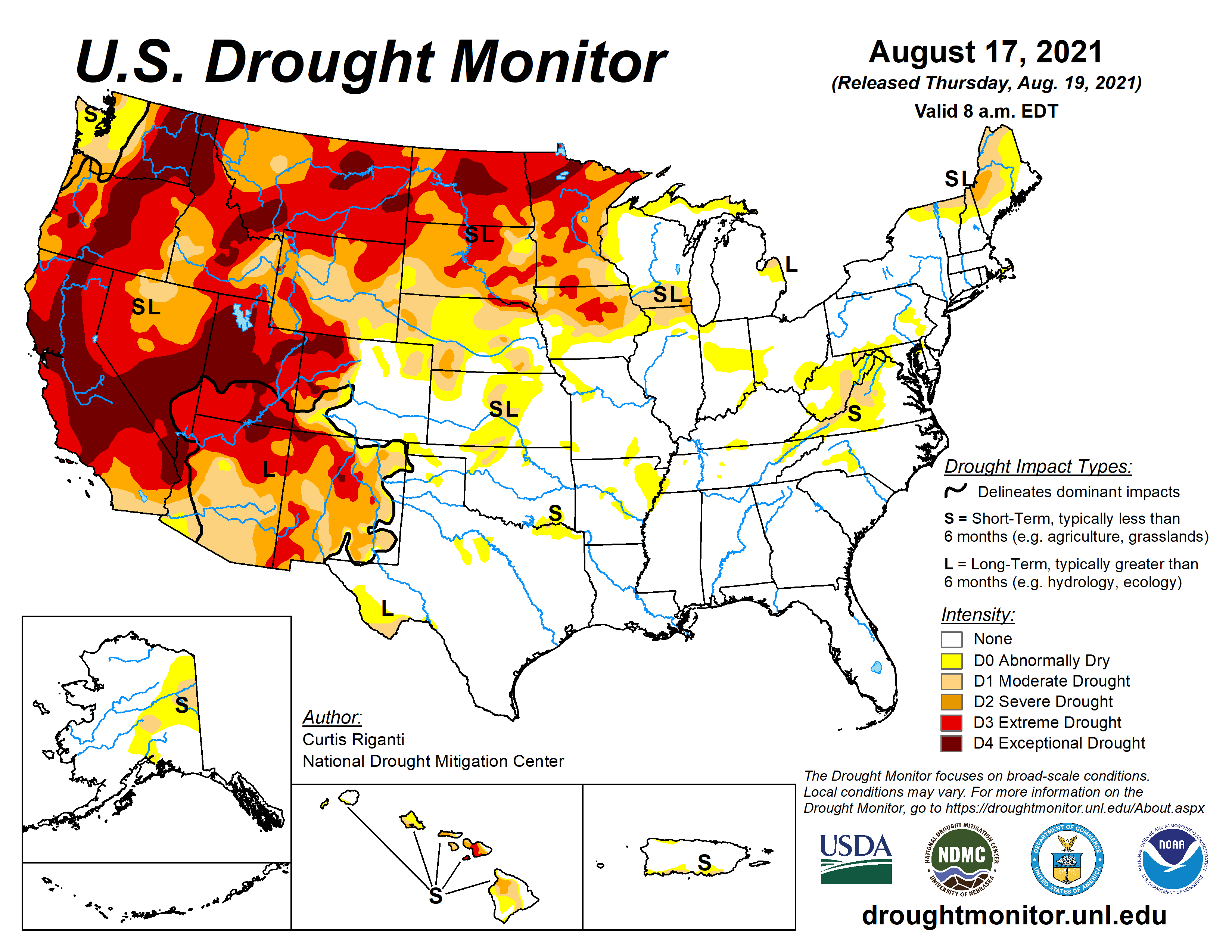

Currently, 88% of Idaho’s land area, encompassing nearly all 44 counties, is experiencing D2 (severe) or higher drought conditions. Fifty-eight percent of the state is concurrently classified as D3 (extreme) or D4 (exceptional) drought. Record high temperatures, rising consecutive days without rainfall and a record number of days with triple-digit heat have been commonplace throughout the 2021 growing season.

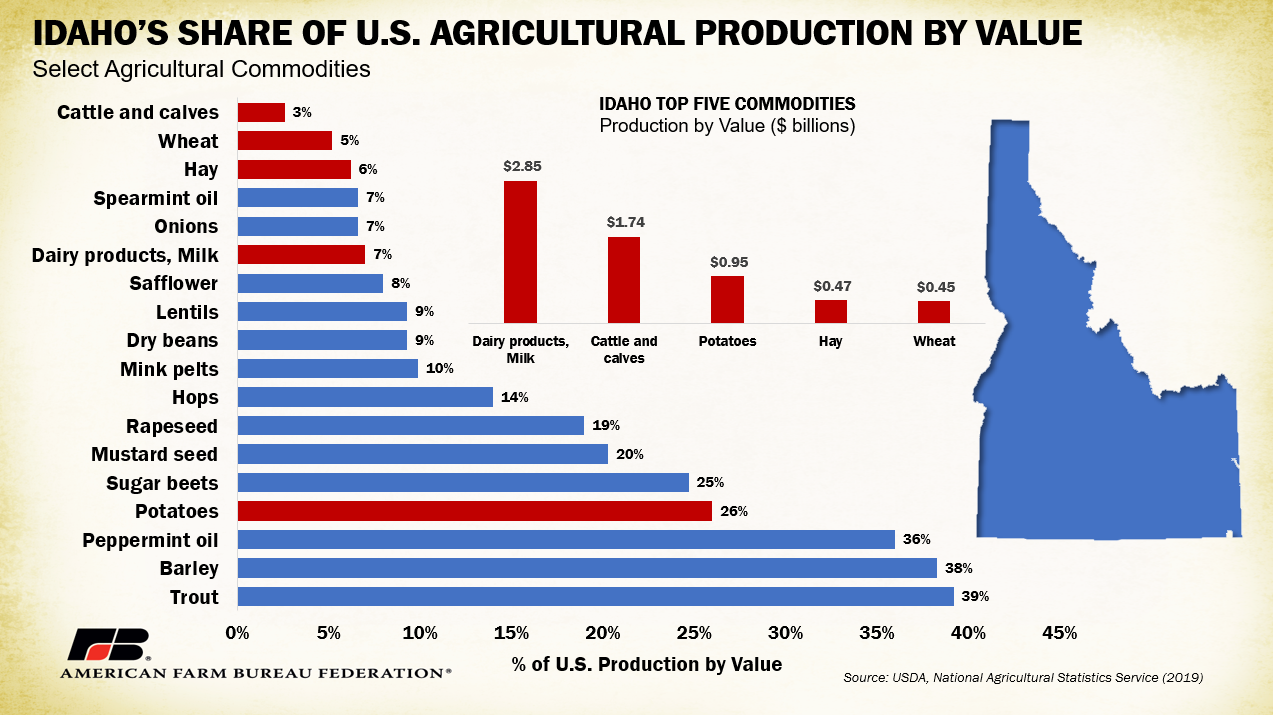

The agricultural industry is one of the most important economic drivers in Idaho, generating over $8 billion in receipts from a diverse set of crop and livestock sources. Of these sources, the largest include dairy and milk production, cattle and calves, specialty crops including potatoes and sugar beets, and forage/feed crops including alfalfa and silage corn. Idaho currently ranks first in the nation in potato production with over 26% of U.S. potato production by value and ranks third in milk production with over 7% of U.S. production by value. Furthermore, over 20% of domestic production by value of trout (39.2%), mustard seed (20.3%), peppermint oil (36%), sugar beets (25%) and barley (36%) is from Idaho.

Of course, all of these sectors and commodities are absolutely dependent on water and moisture. Whether it’s water in the trough for the dairy cow, a running stream or creek that supplies watering systems for the grazing livestock on the range, or water being diverted from the river or pumped from aquifers to irrigate Idaho’s 100-plus crop commodities, water is among the state’s most precious resources.

In Lewis County, located in the Camas Prairie region of north central Idaho, canola and wheat farmer Tom Mosman described the drought challenges in mid-June:

“Typically were are 70-80 bushel dry land wheat… This year if we average 40 or 50 on the fall crop, we will be doing good.”

Idaho can be divided into two categories when it comes to water quantity and supply – those with water storage reserves and those without. Agricultural lands with access to developed water reserves through reservoirs, lakes and aquifers have a stronger chance of getting though this growing season, though significant conservation and curtailment have already begun. Some reservoirs, such as those in the Wood and Lost River basins, are below 7% of total capacity, prompting a number of water managers to stop water deliveries after just 27 days of flow. Many other reservoirs have dropped below 50% capacity including Arrowrock (15%) and Mann Creek (38%) in the West Central Basins, Island Park (48%) and American Falls (15%) in the Upper Snake River Basin and Lake Owyhee (26%) in the Southside Snake River Basin. Many irrigation districts have issued shut-down warnings for September- over a month before the usual cutoff. Certainly, farmers and ranchers without access to developed water reserves who are dependent on precipitation and snowpack have really been devastated.

Northern Idaho and Eastern Oregon farmer Travis Port grows hay and winter peas. Speaking about 2021 production expectations he mentions:

“My projected yield on this, I believe, was going to be around 200 pounds per acre. Our average yield is upwards of 2,000… In our farm in Idaho… our hay production was about half of normal yield.”

The full impact of the multi-year Western drought remains to be seen. Nonetheless, as more crops are harvested and more livestock are brought off the range, we will gain a better understanding of just how damaging these dry conditions have been for farmers and ranchers across Idaho.

Drought Monitor Update

According to the Aug. 19 release of the National Drought Mitigation Center’s U.S. Drought Monitor, nearly 80% of the West plus Minnesota, North Dakota and South Dakota are categorized as D2 (severe drought) or higher. This is an increase from 68.5% the week of June 17 and a sizeable jump from the 34% of the West designated as D2 during the third week of August a year ago. More than 90% of the land area in California (96%), Montana (99%), North Dakota (100%), Nevada (95%), Oregon (99%) and Utah (100%) qualifies at or above the D2 level.

Trending Topics

VIEW ALL