Assessing Western Drought Conditions – Grasshoppers, Fires and Reduced Yields Threaten Montana Farmers’ and Ranchers’ Livelihoods

TOPICS

StillFarming

photo credit: Montana Farm Bureau, Used with Permission

Daniel Munch

Economist

Submission by: Nicole Rolf, Senior Director –Governmental Affairs, Montana Farm Bureau

The infamous drought of 1988 is seared into the memories of Montana farmers and ranchers. People who were farming at the time experienced a combination of heat, drought and pestilence that devastated dry land crops and drove thousands of cattle out of the state. The children of those farmers and ranchers have memories of worried parents and grasshoppers lining the sides of buildings and fenceposts. 1988 may be memorable to people across the country because it’s also the year that just under 800,000 acres burned in Yellowstone National Park, and a total of 1.2 million acres were burned in the Greater Yellowstone Area.

While 1988 was a year for the record books, 2021 is proving to be a strong contender for “worst year in memorable history” for farmers who have worked through both events, and for the current generation of farmers and ranchers who were just kids in the ’80s. Montana experienced several years of severe drought in the early 2000s and had another bad year in 2017, so farmers and ranchers have plenty of recent memories to which they can compare 2021. In 1988, the weather pattern broke and the rain started to return in late fall, but that remains to be seen for much of the state in 2021.

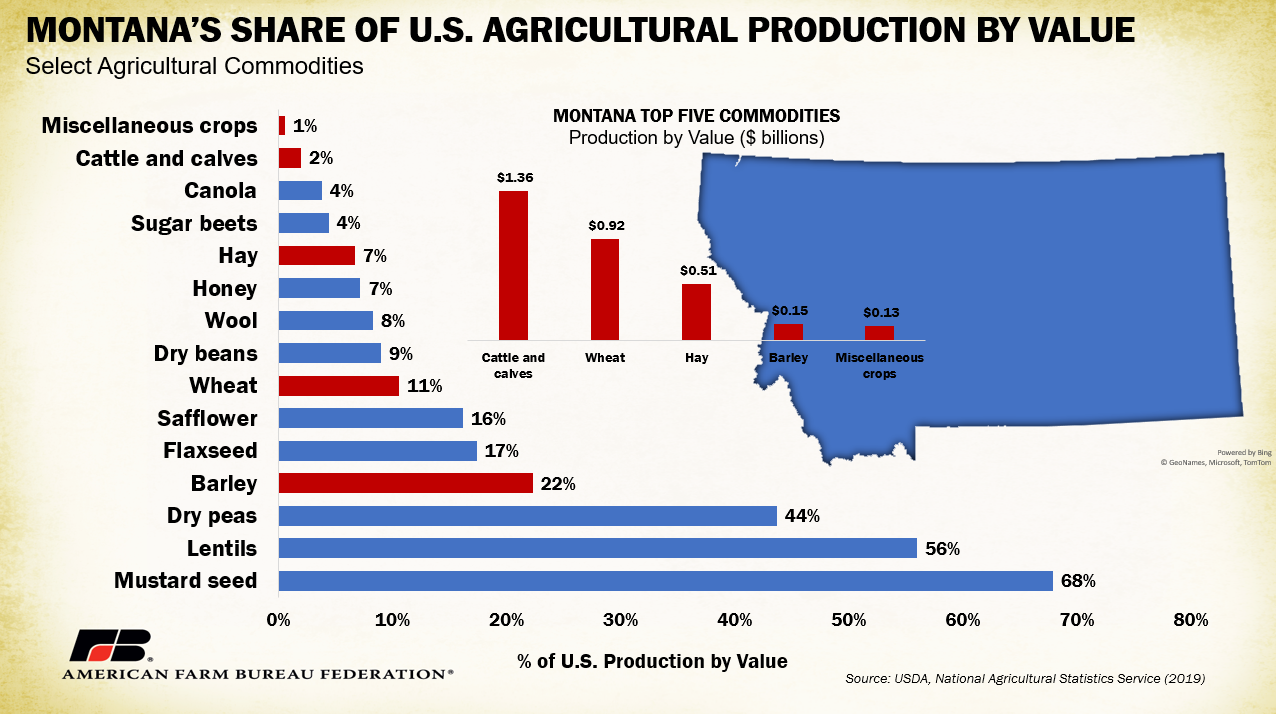

Agriculture is still the leading segment of Montana’s economy, with more than $4.72 billion in gross revenue in 2019. Of that total, cattle and calves are the largest sector ($1.36 billion), followed by wheat ($920 million), hay ($510 million), barley ($150 million) and our variety of pulse crops (dry peas, beans and lentils). Other major crops include sugar beets, honey and oil seeds. Cattle and wheat production consistently rival each other for the top spot and may swap top positions, depending on market prices.

The vast majority of cattle and wheat crops are grown in a dryland setting, making the state’s farmers and ranchers particularly susceptible to drought. In Montana, approximately 66% of land area utilized for agricultural production consists of pasture and rangeland with cropland accounting for 28% and woodlands and farm homesteads capturing the remaining 6%. When it doesn’t rain, no amount of water in a river can address the needs of pasture or dry land farming acres.

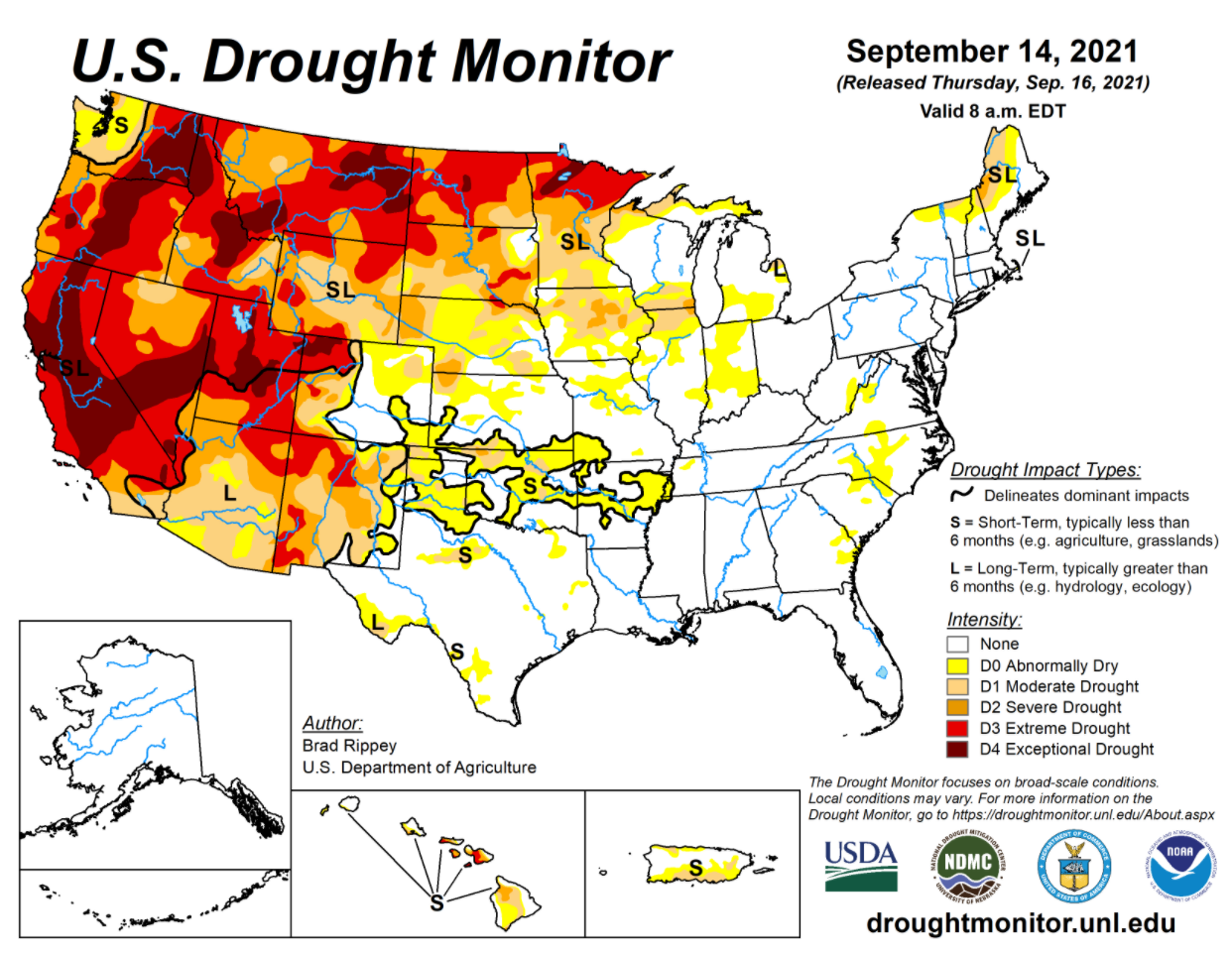

As of Sept. 16, 100% of Montana’s 56 counties were under some sort of drought designation, with 98.7% being in a D2 (severe) or higher designation. More than 20% of the state is designated as a D4 (exceptional) drought, a stark comparison to 0% three months ago and last year. While some portions of the state started receiving moisture in August, May and June, usually Montana’s wettest months, were amongst the driest in recorded history.

In addition to the lack of rain, heat has contributed greatly to the drought. The National Weather Service tracked temperatures through the first two weeks of July in Billings, where the average high was 92.4 degrees, compared to the running average of 85.2. Data for later July and August is not yet available, but anecdotal accounts from farmers across the state indicate that the remainder of the summer will show even more extreme and long-lasting heat events.

It’s not surprising that with this significant level of drought, there have been a high number of wildfires. As of Sept. 10, more than 856,000 acres have burned and that number is expected to grow as there are 40 active fires and a strong possibility that others will start before the “snow flies,” as we say in Montana. Fire is important to note because it’s not just burning trees. Many of these large fires occurred on grazing land, burning across rangeland and cropland, taking what little forage there was, burning haystacks, fences and other types of essential and expensive infrastructure. Sadly, these fast-moving fires often take their toll on wildlife and livestock, despite the best efforts of ranchers who move quickly to get cattle out of the path in time.

Presented is a picture from the Richard Spring fire is southeastern Montana. This single fire burned over 171,000 acres.

A rancher suppressing a grass fire in Yellowstone County, southcentral Montana.

Drought conditions have also exacerbated the prevalence of native grasshoppers that are especially common in the plains regions of the state, where they regularly damage rangeland and cropland. According to the Montana Extension Service, grasshoppers thrive when springtime weather is warm and relatively dry. Warm temperatures accelerate grasshopper growth and limited rainfall diminishes the spread of fungal diseases that harm grasshoppers. 2021 conditions have created a perfect climate for grasshoppers to thrive, resulting in the destruction of forage and cropland acreage across Montana.

Grasshoppers pictured eating the leaves off sagebrush on a ranch in Custer County, southeastern Montana.

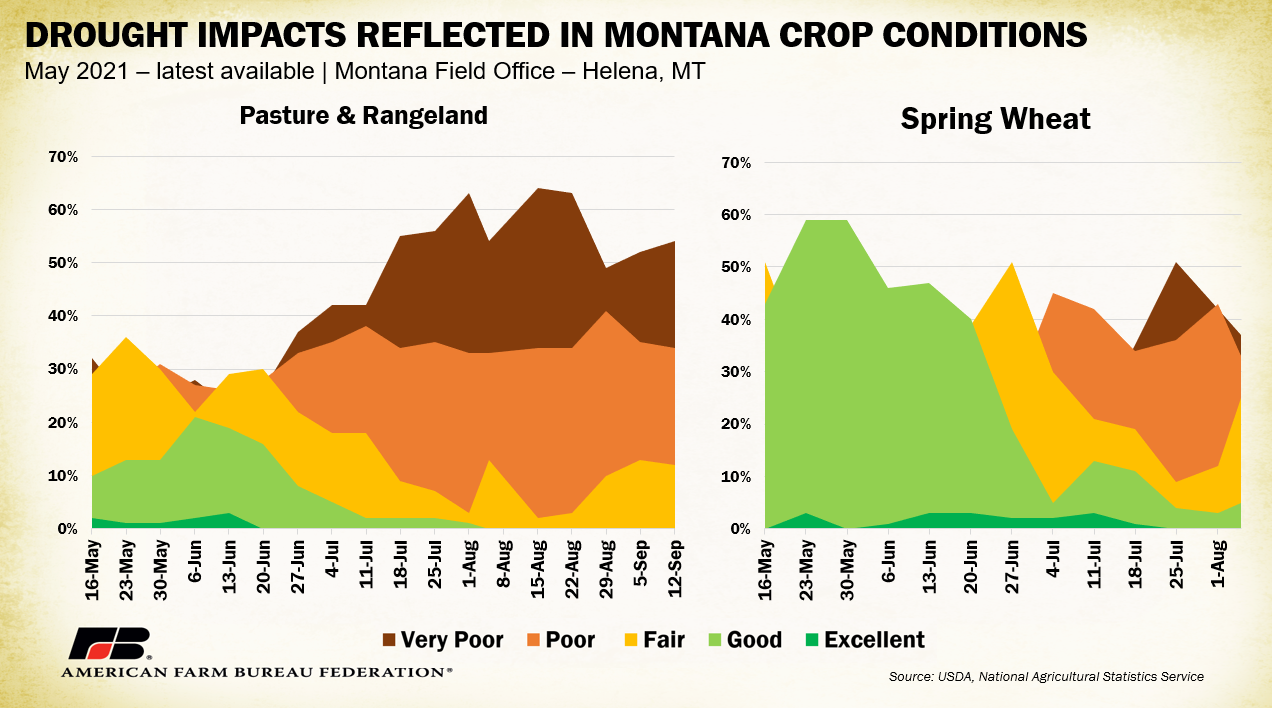

It would be difficult to peg a segment of Montana agriculture that has not been impacted by this year’s drought. Notably, range and crop conditions are poor, crop yields are down substantially, hay and other feed stuffs are in short supply, and irrigators are short on water. As of the Sept. 12 Montana Crop Progress and Conditions Report, nearly 90% of pasture and rangeland were rated as poor or very poor with 0% rated as good or higher. Additionally, 70% of spring wheat was rated poor or very poor just before an earlier than expected harvest in the beginning of August.

Poor range conditions have led to a mass exodus of cattle from the state and the trend is expected to continue. The normal cattle cycle in Montana has calves being born in the spring, weaned in early fall, and pregnant cows retained for the following year. Most weaned calves are shipped to backgrounders or feeders in October or November. Unfortunately, a combination of lack of grass and the expense and shortage of hay has forced ranchers to alter their business plans. Many ranchers sold yearling heifers and cow-calf pairs in May or June. Many calves are being weaned and shipped early to relieve cows of added feed needs associated with milking. These exact numbers are difficult to quantify at this time, but one example is as follows: The Montana Beef Council collected check-off dollars for the sale of 42,898 cattle in August 2020. In August 2021, they collected check-off dollars for the sale of 104,396 cattle- a 143% increase.

Poor crop conditions were especially impactful to spring planted crops. While we will not have final yield data from USDA for some time, Montana Farm Bureau Federation Vice President Cyndi Johnson shared an example of the impacts to her dryland farm in Pondera County, northwestern Montana. Johnson farms in the heart of the “Golden Triangle,” the area known to be the “bread bowl” of Montana.

Spring wheat being harvested in Prairie County, Montana.

Cyndi Johnson at her farm in the Golden Triangle of Montana. Like many farmers, her farm experienced 30% or greater reductions in yield.

Farmer Cyndi Johnson's production yield changes 2020-2021:

Commodity 2020 yield 2021 yield

Dry Edible Green Peas 30-35 Bu/acre 7.5-11 Bu/acre

Winter Wheat 50-55 Bu/acre 35-40 Bu/acre

Spring Wheat 40-45 Bu/acre 25-29 Bu/acre

Like many northern states, Montana ranchers feed their livestock during the winter months. While the amount of feed and the length of feeding varies by ranch, an average rancher will plan to feed hay from November to May. Hay is historically one of a rancher’s largest input costs and this year, because hay is so hard to come by, those costs will be even higher. In the past 10 years, cow-quality hay has varied from $90 to $180 per ton. Hay is harvested from dryland acres, with high quality forages such as alfalfa raised on irrigated fields.

An excerpt from USDA’s Montana Direct Hay Report further describes these challenges:

“This year, dryland hay supplies have been very light to near nil this summer. Many ranchers rely heavily on dryland supplies for hay. According to Montana State there are 2.6 million acres of hay production in Montana and 57% of that acreage is dryland. MSU also states that over 90% of Montana's hay production is fed on site. With much of the state affected with the drought this summer a huge hole in production is being seen as not enough hay has been produced for the amount of cattle in the state. Many hay producers have started on third cutting and some are already finishing up. Some have opted to let third cutting grow as long as possible before cutting as they are hoping to produce as much yield as possible, while other producers cut early as they plan to get a fourth cutting as supplies remain very tight and demand is very good. Hay is being delivered out of local states as well as Canada.”

As noted, many ranchers traditionally raise at least part of the hay they need each year themselves. Unfortunately, in 2021 most saw a significant reduction in production, and some did not cut a single acre because of crop failure or because grass and even planted forages did not grow high enough to cut with a swather.

A field of ungerminated spring triticale that would have been harvested for hay located in Mussellshell County, central Montana.

Range water supplies have taken a hit as well. Many ranches rely on reservoirs to water cattle and sheep. Here is a side-by-side example of a stock reservoir in Prairie County, eastern Montana. The first picture was taken in August 2020 and the second in August 2021.

A view of the same reservoir in Prairie County, Montana, August 2020 vs. August 2021.

Summary

While the drought of 2021 will likely capture the infamous spot of “worst summer in memorable history” for Montana farmers and ranchers, the landscape is incredibly resilient. Fall rain and normal snowfall will go a long way toward restoring much-needed soil moisture, snowpack and water supplies. Montanans like to say, “This is next year country,” and we are anxiously looking forward to 2022.

Photo caption: A red sun sets over fall leaves in early September. Despite the severe drought, a recent .4 inch rain prompted wild flowers to bloom, showing the resiliency of the land and the people who make their living here.- Nicole Rolf

Drought Monitor Update

According to the Sept. 16 release of the National Drought Mitigation Center’s U.S. Drought Monitor, nearly 75% of the West plus Minnesota, North Dakota and South Dakota are categorized as D2 (severe drought) or higher. This is a sizeable jump from the 43% of the West designated as D2 during the third week of September a year ago. More than 90% of the land area in California (94%), Montana (99%), North Dakota (92%), Nevada (95%), Oregon (99%) and Utah (100%) qualifies at or above the D2 level.

Trending Topics

VIEW ALL