Assessing Western Drought Conditions – Farmers and Ranchers in the Nation’s Driest State Put to the Test

TOPICS

StillFarming

photo credit: Montana Farm Bureau, Used with Permission

Daniel Munch

Economist

Submission by Brittney Money, Director of Communications, Nevada Farm Bureau

Nevada has never had an abundant water supply. In fact, with an average annual precipitation of only 10 inches, Nevada is the driest state in the United States. Nevada’s diverse landscape ranges from snowy mountain tops to sandy deserts and sagebrush valleys in between. The high mountain tops receive closer to 50 inches of snowfall or more in a good winter, but actual precipitation for most of the state is 4 inches.

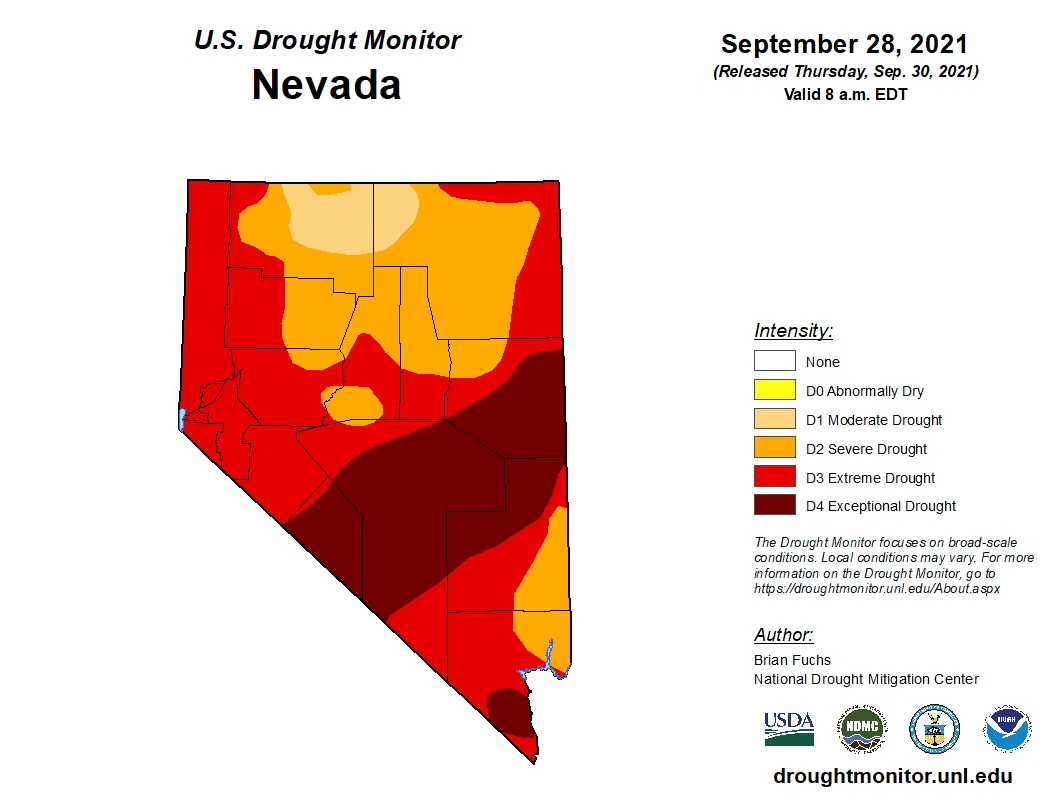

Average annual precipitation totals at those levels make it no surprise that 100% of the state is in D1 (moderate) drought or higher, 95.2% is in D2 (severe) drought or higher, 67.6% is in D3 (extreme) drought or higher and 25.9% is in D4 (exceptional) drought. The range of drought levels highlights how diverse the state is and shows what the more than 3,400 farms and ranches in the Silver State are up against.

When people think of Nevada their first thought is often Las Vegas, but 13 of the state’s 17 counties are classified as rural. Agriculture is one of the leading contributors to rural economies throughout the state, with alfalfa hay the leading cash crop. Farmers and ranchers in the state also produce range livestock (of cow-calf or sheep operations), dairy, alfalfa seed, grass hay, potatoes, barley, winter and spring wheat, corn, oats, onions, garlic and honey.

Most of the crops grown throughout the state are not water-intensive, but that does not make the lack of water any less crucial to the success of agriculture here. Most Nevada farmers are constantly adapting and adjusting to drought that seems to be intensifying as temperatures rise.

Nevada Farm Bureau Vice President Darrell Pursel has endured the need for water. Pursel, a Lyon County alfalfa farmer and a cow-calf rancher, expresses his frustration with how the lack of water has affected his farm this year: “It seems we are working hard or harder to get nothing or very little at all.”

Many farmers throughout the state have wells or rely on water from reservoirs and rivers. Farmers with wells are largely continuing with business as “normal.” Producers like Pursel who rely on other sources like surface water flows from reservoirs and rivers are greatly feeling the impacts. Those who get irrigation water from surface sources are getting a lower water allocation than normal and even had their water temporarily shut off early this year. Anticipating drought conditions early on, many farmers pivoted to alternative production options, targeting priority crops or more productive fields, planting less or leaving some fields unplanted.

Expecting drought and adapting doesn’t make it any easier for the farmers and ranchers. Pursel is anticipating having one-third of his normal alfalfa to sell. Along with less alfalfa, he’s expecting his beef cattle will come in at 100 pounds per animal less than normal. Without water, there’s less pasture for the cows to graze on, which means supplementing more with alfalfa.

“Learning to adapt is the hardest thing. I am used to doing custom work on top of the alfalfa I sell for extra income and with such little water I have had to focus on just the alfalfa to keep everything afloat,” said Pursel. “I don’t know what we will do if we don’t get moisture this winter. It’s better to not think about that yet.”

For those who aren’t as lucky to have hay on hand, the situation is much more dire as the prices for hay – that’s if you can find it -- climb higher. Lasting through the winter will be the true test for some.

From one area of the state to another, everyone’s story seems to be the same: if you have hay, you are in great shape. Hopefully your hay supply can survive the drought, or at least the winter. If you have a well and are growing alfalfa with extra to spare, with prices at premium, you are in even better shape.

Winter will be an anxious time for farmers and ranchers across Nevada. As we hope for moisture throughout the state, the next few months will be the true indicator of how impactful this dry year truly was.

Lahontan Reservoir is a part of the first federal Bureau of Reclamation project – the Newlands Irrigation project - completed in the United States. This reservoir has a capacity of 295,500 acre feet of water (an acre foot of water is just under 325,000 gallons of water). Lahontan Reservoir receives water from the Carson River and, under specified conditions, through a diversion of the Truckee River. The Carson River system has its headwaters in the Sierra Mountains, just south of Lake Tahoe. The Truckee River originates from Lake Tahoe and flows through the Reno/Sparks area before reaching the Derby Dam diversion east of Reno/Sparks. When Truckee River water isn’t being diverted it flows to Pyramid Lake. This year’s irrigation season concluded in mid-August when water levels fell below the minimum pool requirements to be kept in the reservoir.

The Newlands Irrigation project covers 57,000 acres of cropland and was authorized by Congress in 1903.The first irrigation season for the project was in 1905 and the Lahontan Dam, which holds the water in the Lahontan Reservoir before distribution through irrigation canals, was completed in 1914.

This is a current photo of the Carson riverbed just before water (if it were flowing) would enter the Lahontan Reservoir. The Carson River originates in the Sierra Mountains south of Lake Tahoe.

Drought Monitor Update

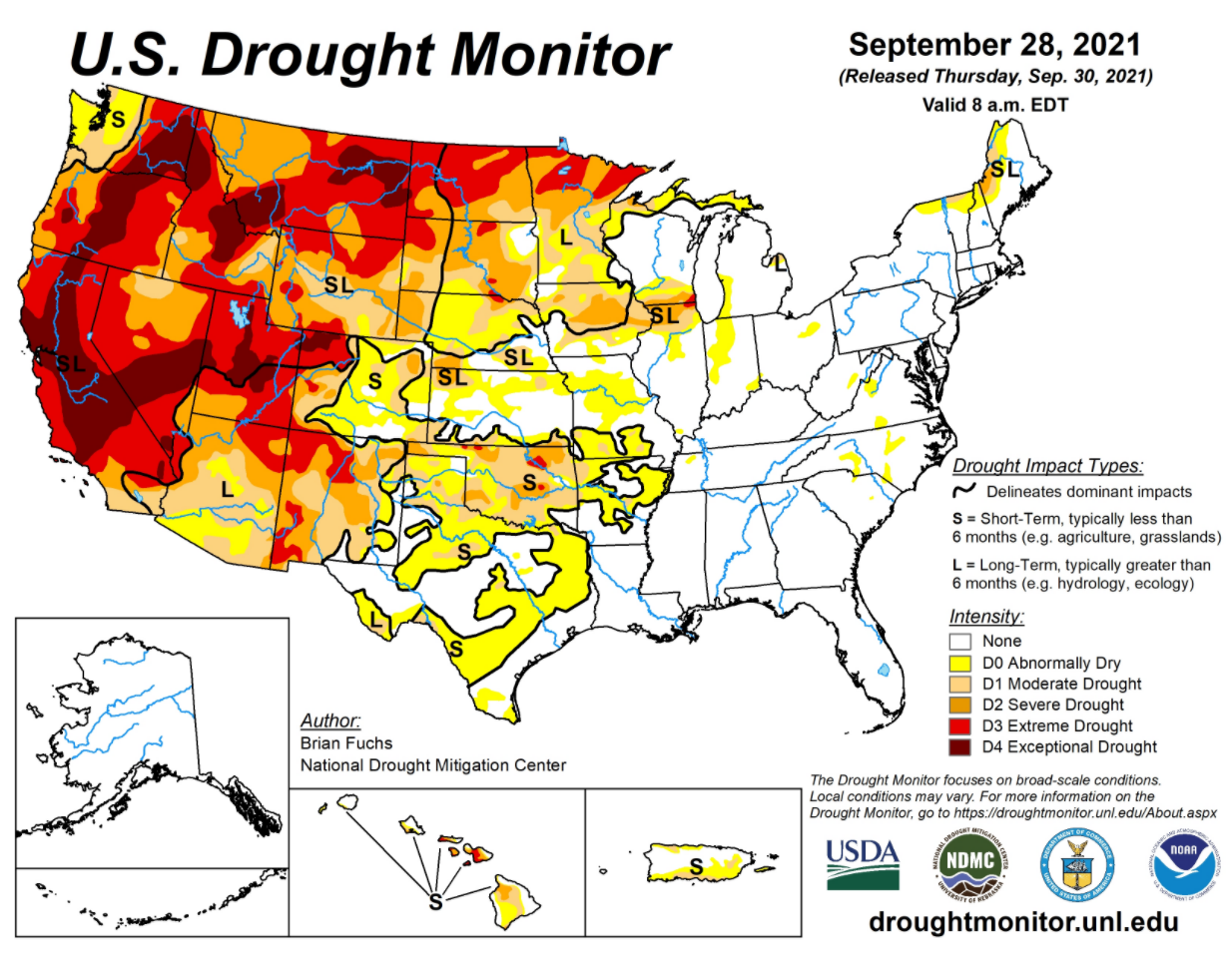

According to the Sept. 30 release of the National Drought Mitigation Center’s U.S. Drought Monitor, nearly 75% of the West plus Minnesota, North Dakota and South Dakota are categorized as D2 (severe drought) or higher. This is a sizeable jump from the 47% of the West designated as D2 during the last week of September a year ago. More than 90% of the land area in California (94%), Montana (100%), North Dakota (92%), Nevada (95%), Oregon (96%) and Utah (100%) qualifies at or above the D2 level.

Trending Topics

VIEW ALL