Assessing Western Drought Conditions – California Farm Bureau President Opens Window into State’s Water Management Woes

TOPICS

Water RightsAFBF Staff

photo credit: Nancy Caywood, Used with Permission

By Jamie Johansson, President, California Farm Bureau

California’s water history flows across my farm in the North State community of Oroville. A canal carved in the early 1990s passes beneath my olive groves. It was an extension of original conveyance systems inspired by gold seekers, who fashioned one of California’s earliest water delivery systems in the 1890s on the Feather River, near my home.

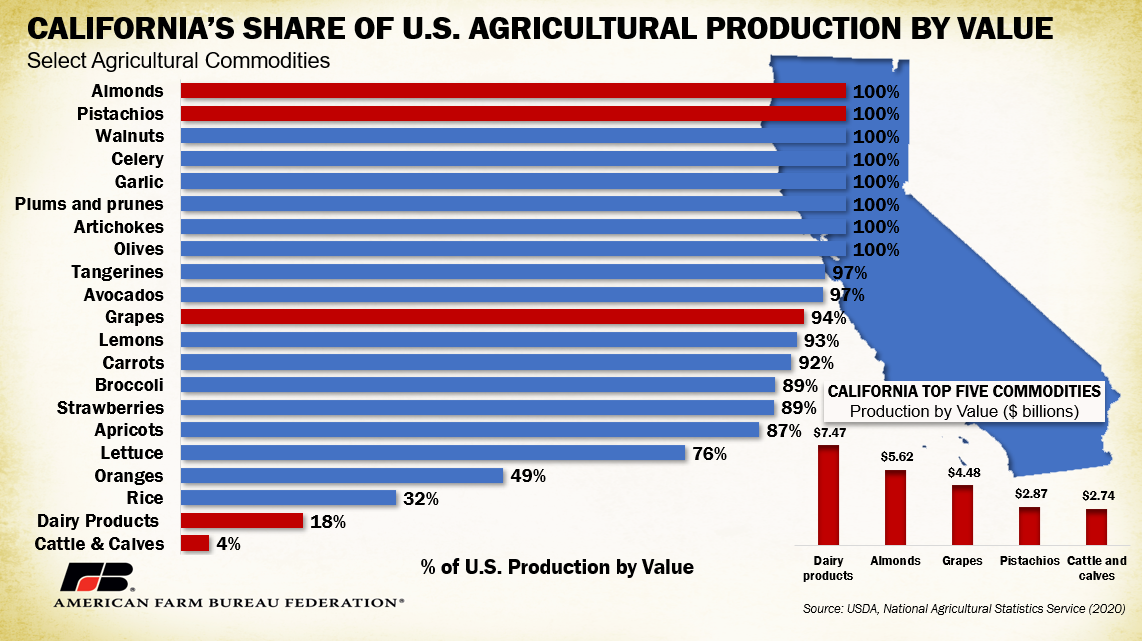

Those systems were later built upon as the lure of gold gave way to the great agricultural promise of California. That promise—and the availability of water—lured a local farming pioneer from Illinois to Northern California. Freda Ehmann became the acclaimed “Mother of the California Ripe Olive Industry” and continues to inspire my farm’s mission to carry on her traditions in producing California olives.

Now, as president of the California Farm Bureau, I am fighting to uphold and restore the promise of sustainable water delivery in my state. After two years of severe drought, our farmers and ranchers are suffering. They’re fallowing crops and thinning herds because of extreme water shortages.

That isn’t surprising in a state in which surface water supplies from the critical Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta were effectively cut off in August for 10,300 water-rights holders and 4,500 Central Valley farms. And yet, given California’s history of water engineering and innovation, it’s shocking.

Those early canals led to the concept of a statewide water development project. The effort culminated in the creation of the California State Water Project, a system of reservoirs, hydroelectric power facilities, canals and pipelines that deliver water to 27 million Californians and 750,000 acres of farmland. It would complement the larger Central Valley Project, a federal system of dams and reservoirs that in normal years delivers water to one-third of the agricultural land in California.

These projects were the essence of the California promise: to continue innovating to support our growing Golden State communities and our prospering farming and ranching sectors. That included supporting entrepreneurialism while also safeguarding the environment.

But then somehow California lost its way. Even after a historic drought in 1976-77, the state couldn’t seem to muster its spirit of innovation for continuing to grow its water infrastructure with new storage facilities and upgraded conveyance systems. These days, our once world-renowned water system is aging and ill-equipped for California’s 21st century water needs.

The results are painful for California agriculture. That’s clear from the American Farm Bureau Federation’s drought survey this summer, which included responses from 480 California farmers and ranchers.

According to the California survey numbers, 25% of our growers said they were highly or extremely likely to plow under crops due to fears of inadequate future water deliveries for irrigation, and 41 % said they were likely or extremely likely to remove orchard trees.

Our ranchers weren’t faring any better. More than half of those surveyed said it was likely or extremely likely that they would thin their herds and flocks. Nearly two-thirds said they would pull animals from rangeland because of insufficient forage due to drought.

It’s not entirely fair to say California lost its water vision. But sadly, California can’t get out of its own way.

In 2014, 67 % of California voters approved a potentially landmark water bond measure, Proposition 1. The Water Quality Supply and Infrastructure Act allocated $7.1 billion in bonds for modernizing our water system with vastly expanded surface and groundwater storage, upgraded conveyance, public water system improvements and investments in ecosystem protection and restoration.

Yet not a water’s drop of infrastructure has been built since. Litigation, infighting and a lack of political will have blunted the progress California voters demanded.

Recently, a powerful storm brought a welcome—though far short of drought-busting—deluge to Northern California. Had it been built by now, the signature project of Proposition 1—the proposed Sites Reservoir near Sacramento—could have captured much of that rainwater.

But our farmers and ranchers are not giving up. The California Farm Bureau has continued to fight for federal and state water infrastructure improvements, and we were heartened by the recent allocation of $80 billion in federal funds for planning and engineering for the Sites Reservoir.

It’s true that water projects take time. In my community, the Oroville Dam—a major storage facility of the State Water Project—took more than eight years to build after its approval in a 1960 water bond.

Still, we must retain the fierce urgency of our forebearers, including farmer settlers who saw the promise of California and worked to build water storage and conveyance for future generations.

We are indeed still farming in California. Our agricultural communities are evolving in the face of epic challenges. But we will not rest until we secure our water future, fulfilling our obligations to the farmers and ranchers who will follow us in the years ahead.

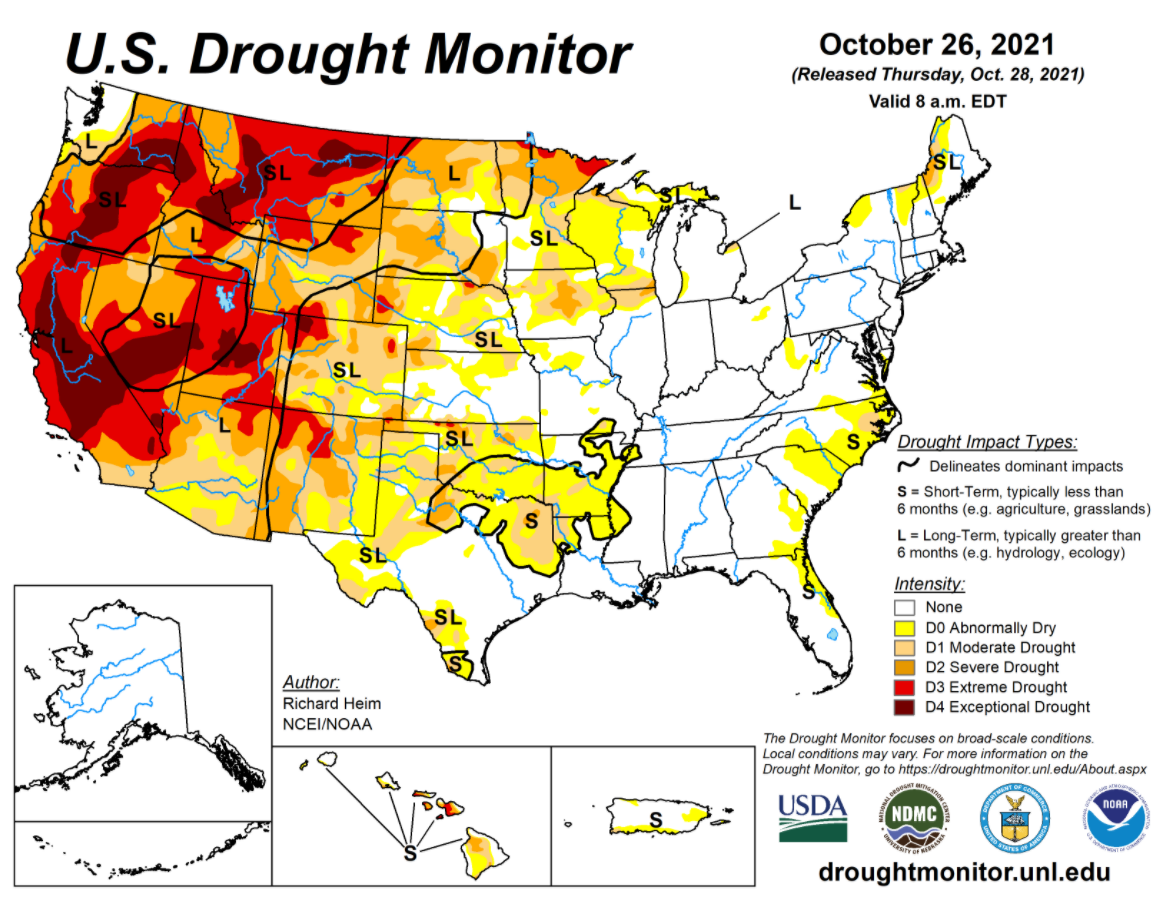

Drought Monitor Update

According to the Oct. 28 release of the National Drought Mitigation Center’s U.S. Drought Monitor, nearly 70% of the West plus Minnesota, North Dakota and South Dakota are categorized as D2 (severe drought) or higher. This is a sizeable jump from the 50% of the West designated as D2 during the last week of October a year ago. More than 90% of the land area in California (94%), Montana (100%), Nevada (95%), Oregon (96%) and Utah (100%) qualifies at or above the D2 level.

Trending Topics

VIEW ALL