Assessing Western Drought Conditions – A Snapshot of How Arizona’s Farmers and Ranchers are Coping with Drought

TOPICS

Weather

photo credit: Nancy Caywood, Used with Permission

Daniel Munch

Economist

This is Part Two in a Market Intel series showcasing the impacts of drought conditions in the Western U. S. Part one presented the first set of results from AFBF’s Assessing Western Drought survey. This iteration highlights a guest author submission from Arizona Farm Bureau illustrating state-specific hardships faced by farm and ranch families in the region.

Submission by Chelsea McGuire, Director of Government Relations, Arizona Farm Bureau

Even for a desert state, the last three years have been dry in Arizona. As of June 11, fourteen of Arizona’s fifteen counties were in D4 (exceptional) drought designation. The same drought that rages across the entire American West is threatening the livelihoods of Arizona’s farmers and ranchers, no matter the commodity they grow. The impacts have been devastating to the state’s $23.3 billion agricultural industry, in ways that may change the face of farming and ranching in Arizona for generations to come.

Arizona’s primary land use is livestock grazing. The state is home to more than 6,000 cattle ranches that cover 73% of the state’s total land area. Ask any of the ranchers who manage those 6,000 ranches and they will tell you they spent the first half of 2021 hauling water. Without any rain, ranchers are hauling 100% of the water that they can’t get from pumps or pipelines. This water costs 1 to10 cents per gallon, not including the cost of labor, equipment and maintenance necessary to deliver it where it needs to go. No rain also means no forage. As a result, ranchers have reported up to 94% increases in hay purchases as compared to this time last year. But the impacts of low forage supply are not exclusive to dry years. Many ranchers pride themselves on pasture rotation systems and forage management plans, but dry years make it impossible to sustain an economically feasible carrying capacity while also leaving some pastures in reserve.

To get by, most ranchers have sold significant portions of their herds. But because every ranch in the state is in the same boat – one with no water under it – the market is not favorable to ranchers looking to liquidate. One rancher reported that the price for cow-calf pairs has dropped by about 60% in the last 18 to 24 months.

While hauling water and supplementing with protein can help bridge the gap until there is water and forage available, at the end of the day, there’s simply no way to make it rain. Instead, ranchers must look elsewhere for resources to help them make it through these dry times. Ranchers welcome the tools available to them through USDA, and many have found programs including Pasture, Rangeland, and Forage Insurance, the Emergency Assistance for Livestock Program and the Noninsured Crop Assistance Program to be extremely helpful. Despite the availability of this relief, every rancher surveyed on drought issues indicated that they plan to sell between 50% to 100%t of their herds unless drought conditions significantly improve.

We believe in banking grass for the bad years. We like to leave a reserve of grass every year. We keep our herd numbers lower to be able to do this . . . but now we are down to the last blade of grass.

Arizona Rancher Tina Thompson

Regionally, crop production is also facing severe challenges due to drought, and there’s no better example than Pinal County, located in the heart of central Arizona. According to the 2017 Census of Agriculture, Pinal County is home to 232,224 irrigated acres. In a study conducted by the University of Arizona, Pinal County was found to account for 42% of the state’s cotton and cottonseed sales, 39% of milk sales and 22% of hay sales, which support milk production. Overall, agriculture contributes $2.3 billion in economic impact to the county. And it’s not just on a local level that Pinal County agriculture punches above its weight class. Pinal County is in the top 2% nationwide in terms of total value of agricultural sales.

That bounty was made possible by water coming from two major sources: the ground, pumped through wells, and the Colorado River, delivered through a 336-mile canal known as the Central Arizona Project . Water used by states in the lower Colorado River basin is subject to a complex priority system. Pinal County farmers, who rely on CAP deliveries for about half of the water they use, have the lowest priority access to Colorado River water. This means that shortages on the river impact them first. Currently, it’s all but certain that the Bureau of Reclamation will declare a Tier One shortage on the Colorado River in mid-August.

When that happens, Pinal County agriculture will lose access to 300,000 acre-feet of water, with no readily available replacement in sight. The next alternative is increasing the level of groundwater pumping to make up for lost surface water. But it will take at least $50 million to rehabilitate existing/install new well infrastructure to make that a possibility. Although efforts have been made to mitigate the impact of this shortage with surface water (agreements from higher-priority users to forego some of their Colorado River allotments, for example), there is simply not enough water available from any source, surface or ground, to make up for the loss of water and production capacity that is now inevitable in Pinal County. The University of Arizona estimates that the economic impact of losing that water will include a loss of more than $100 million in sales, $66 million in gross farm-gate sales and up to 480 full or part-time jobs.

On a more positive note, Arizona is working hard to define what the next frontier of agriculture will look like in our state. Knowing that drought is one of the biggest threats to their livelihood, farmers and ranchers across the state have invested millions of dollars over the last few decades to make sure that no drop of water is wasted. Ranchers have invested countless dollars in water conservation infrastructure like tanks and pipelines and have worked for generations to develop precise and science-based forage management practices. Farmers have laser-leveled fields, installed computerized drip irrigation systems and contracted with third parties to grow alternative low-water crops.

July 2021 was a month of record-breaking monsoon rainfall in Arizona, and for that, our farmers and ranchers are grateful. But one month of moisture does not a megadrought fix. Arizona’s agricultural community remains committed to using every drop as effectively and efficiently as we can while also working with elected officials at every level of government to craft relief programs providing a life raft so that, when there is water, agriculture will still exist to use it. Right now, only one thing is certain: without a significant improvement in hydrological conditions, that future cannot, and will not, look like the thriving agricultural economy of today.

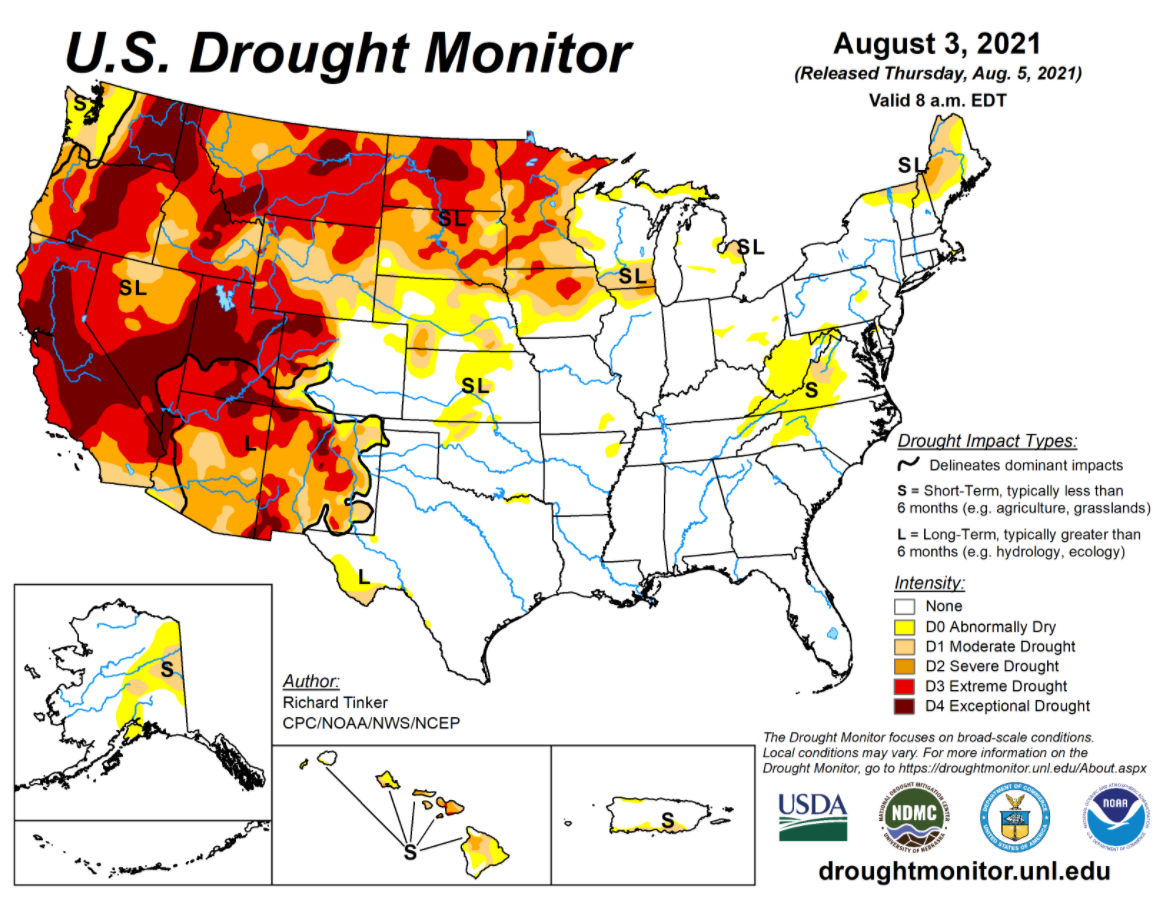

Drought Monitor Update

According to the Aug. 5 release of the National Drought Mitigation Center’s U.S. Drought Monitor, more than 80% of the West plus North and South Dakota are categorized as D2 (severe drought) or higher. This is an increase from 68.5% the week of June 17 and a big jump from the 29% of the West designated as D2 during the first week of August a year ago. More than 90% of the land area in California (95%), Montana (99%), North Dakota (98%), Nevada (95%) and Utah (100%) qualifies at or above the D2 level.

Trending Topics

VIEW ALL