As Processing Facilities Struggle with Labor, Spread Between the Wholesale Price of Meat and Livestock Prices Widens

TOPICS

MeatMichael Nepveux

Economist

photo credit: Colorado Farm Bureau, Used with Permission

Michael Nepveux

Economist

The self-distancing and quarantine protocols put in place to slow the spread of COVID-19 have reduced economic growth, shuttered consumers in their homes and changed the way Americans purchase and consume food.

Food production, too, has been significantly disrupted, especially at livestock processing facilities, where labor shortages and worker protection measures are slowing throughput at plants around the country and even causing some facilities to shut down. In late April President Trump signed an executive order designating these companies as critical infrastructure and instructing them to remain open when possible, abiding by CDC guidelines to protect workers.

At the same time considerably fewer cattle and hogs are being processed, wholesale meat prices are rising and the gap between the value of meat products and the prices that producers receive for their livestock is growing. That widening gap caught the attention of President Trump, who recently voiced his concerns about the situation. President Trump asked the Department of Justice to investigate whether or not meat processing companies participated in price fixing after attorneys general from 11 states issued a letter urging that action.

Strained Processing Capacity

Over the past two months, more than two dozen livestock processing plants have closed down due to issues with COVID-19, for periods ranging from a few days to two weeks or even indefinitely. In some cases, the closures were due to outbreaks among workers at the plants. In other cases, it is a struggle to keep workers, who are afraid of getting sick, coming into the plant. Some of these facilities, such as the JBS facility in Greeley, Colorado, have already reopened. That makes estimating the country’s processing capacity a moving target, but we can estimate that at times over the previous few weeks, pork processing capacity has been reduced by as much as 20% and beef processing capacity has been reduced by as much as 10%.

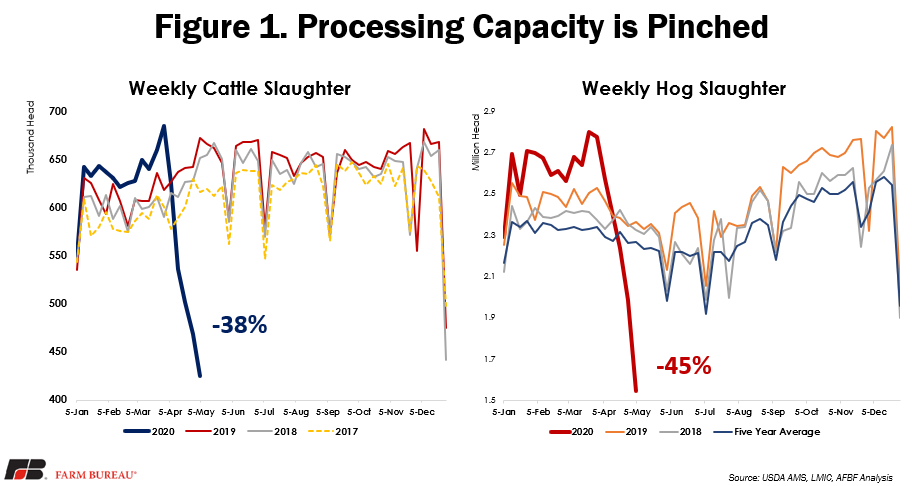

These estimates are derived from publicly available information and company announcements about packing plants and further processing facility closures. They do not factor in reductions in capacity due to slowing throughput and reduced line speeds at these facilities, which are also reducing capacity. In an effort to protect employees, processing companies are implementing new policies (such as installing plexiglass barriers between workers, spacing employees further apart, etc.) and incorporating more social distancing in their facilities, which slow the flow of product through their lines. This reduction is more difficult to quantify but has the potential to have more far-reaching impacts than direct plant closures. One data point that we can use as a proxy for this difficult-to-gauge number is overall weekly slaughter of cattle and hogs. Figure 1 shows the drastic drop in slaughter numbers for hogs and cattle. Weekly total cattle slaughter has decreased by 38% since its March high and 34% from the previous year. Weekly hog slaughter has dropped 45% from its earlier high and 35% from 2019.

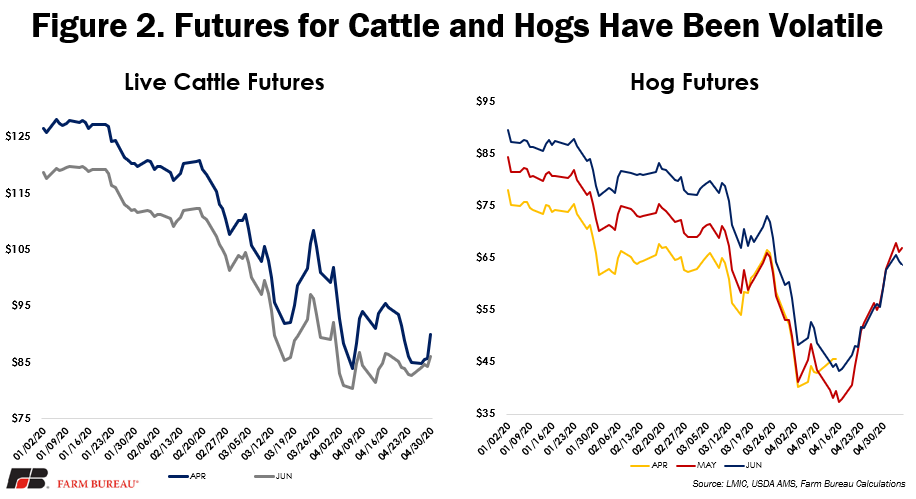

Without the processing capacity, plants cannot take delivery of animals, driving down prices paid to producers and creating backlogs throughout the system. Figure 2 shows the dramatic decline in live cattle futures and the roller coaster that lean hog futures have been on.

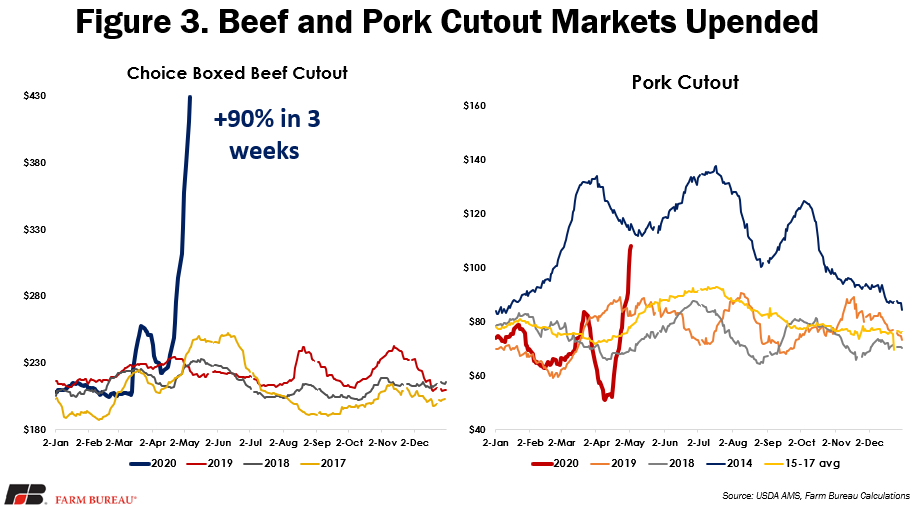

With limited processing capacity also comes lower output of meat and poultry products, which has pushed wholesale prices way up. The choice boxed beef cutout has surged well beyond historical levels, nearly doubling in value in just three weeks. The pork cutout has increased 103% since April 15 but remains (for now) below the highs in 2014, when PEDv decimated the country’s pork industry.

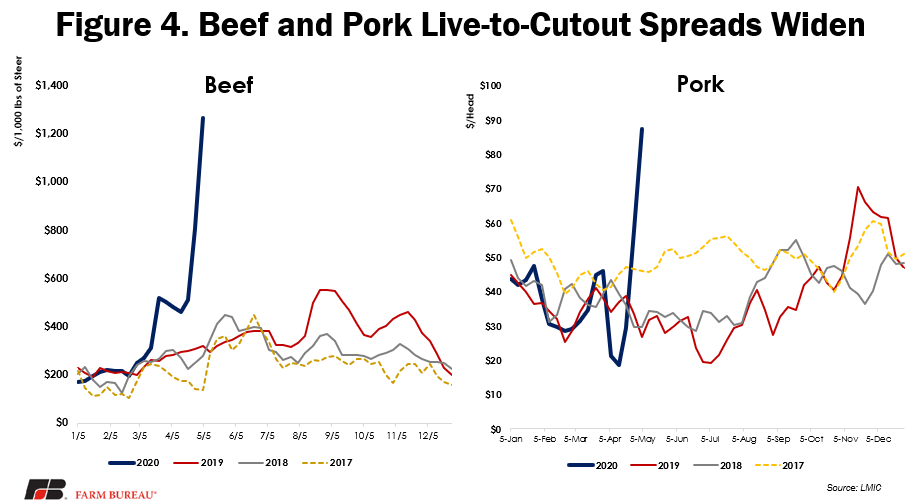

As wholesale prices for meat skyrocket and livestock prices plummet, the live-to-cutout spread for beef is widening to the degree it caught President Trump’s eye. Figure 4 shows the increase in the live-to-cutout spreads for beef and pork. This spread comes from the Livestock Marketing Information Center’s database of calculated gross margins on a 1,000 lbs.-of-steer basis and per head of hog basis. These calculations are essentially the spread between inputs and outputs and do not include processing costs (energy, labor, etc.) and fixed costs.

It is tempting to look at Figure 4 and draw conclusions about packer margins, but while the live-to-cutout spread typically provides a good measure of the overall health of packer margins, the current environment makes that incredibly difficult to gauge. Processing plants’ new COVID-19 safety measures add a cost that is not included in the spread. There is no way to know that cost outside of getting a look at the processing companies’ internal information, but one can infer that the cost of protective gear, increased sick leave, increased bonuses and increased incentive pay are very high for these businesses.

Additionally, while a plant may be profitable while operating at 90%-100% capacity, that may not hold true at 50% capacity, even with record-breaking spreads. The fixed costs associated with operating a plant come in many forms, including massive asset investment costs and large regulatory costs. The companies normally spread those costs over many animals when operating at or near full capacity, but when capacity is reduced significantly, the ability to operate profitably declines as they spread these fixed costs out over fewer animals. It is important to try and account for reduced throughput and increased COVID-19-related costs as these impact processer profitability. While there is no way to know for sure the profitability of some of these plants, it is certain that the picture is much murkier than a simple cursory look at Figure 4 would tell you.

Conclusion

This global pandemic has injected never-before-seen uncertainty into the animal protein markets. As processing plants struggle to remain open amid labor shortages and maintain line speeds while implementing worker protection measures, the wholesale value of meat has surged. At the same time, livestock prices have cratered, leading to very large spreads between the value of a processing facility’s inputs and outputs. However, with the increased costs of doing business in a COVID-19 world, the actual situation on the ground is going to be a bit more complicated than at first glance.

Trending Topics

VIEW ALL